8% of all male homicides are committed by police, study says — and black men are most at risk

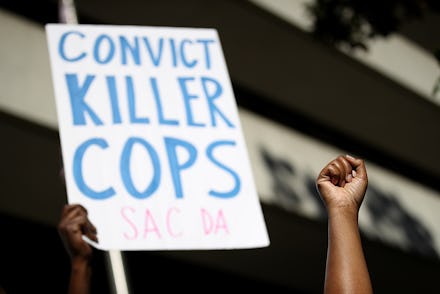

Police violence against black people and other people of color is a forefront issue in 2018 America. It’s a source of protests and strong political movements — or utter denial, depending on who you ask. President Donald Trump has openly mocked the issue, telling officers in Long Island to “please don’t be too nice” to suspected gang members. He also joked that police should not protect cuffed suspects’ heads from hitting the top of the police car as they’re lowered into the backseat.

In sum, Trump fails to acknowledge police violence and has even been dubbed “the brutality president.”

But now, there’s a growing amount of indisputable evidence showing the U.S. really does have a serious law enforcement problem. Police committed roughly 8% of all U.S. homicides involving adult male victims between 2012 and 2018, according to new study published in the American Journal of Public Health.

That’s nearly three men killed every day over the course of 6.1 years. And yes, black men were at a disproportionately high risk.

“Eight percent of all men killed in the U.S. are killed by cops,” Frank Edwards, an author on the study and a postdoctoral associate at Cornell University’s Bronfenbrenner Center for Translational Research, said. “That’s huge, and that number is even higher in some places than others. That’s really striking, to think of police as a major source of homicide deaths. It’s a public health problem.”

Edwards and his colleagues came up with these numbers by running statistical models through data collected by a group called Fatal Encounters. Fatal Encounters archives every news report or public record it can find involving deaths that occur during interactions with police.

A total of 8,581 men died during police encounters between 2012 and 2016, according to the organization. But after filtering out cases of suicide or accidental death, researchers concluded 6,295 men were killed by police use of force.

The data used isn’t perfect, but it’s certainly better than what the U.S. government’s Bureau of Justice Statistics publishes. While Fatal Encounters might be missing some cases that never garnered media attention, the Bureau of Justice Statistics relies solely on voluntary reporting. Police agencies are not required to submit any incidences of death caused by or in the presence of its officers. And with all the controversy surrounding police brutality, it’s easy to understand why many law enforcement offices aren’t forthcoming.

“If you’re a police agency, reporting on officer-involved deaths is not necessarily something you’re going to gleefully do,” Edwards said. “It’s troubling, but wonderful, that we had to rely on independent journalists and news organizations [for these data]. It’s far more comprehensive than anything the government has put together.”

It’s true: Black men suffer the highest rates of police homicide.

After analyzing the differences in race, Edwards and his colleagues found black men were up to three times more likely to be killed by police than white men. The mortality risk among black males is between 1.9 and 2.4 deaths per every 100,000 people each year. For Latino men, risk is between 0.8 and 1.2 deaths per every 100,000 people — and for white men, the number comes out to roughly 0.6 or 0.7. Researchers focused on men of these backgrounds because data on women, Asian Americans, Native Americans and other demographics weren’t robust enough to run through their statistical models.

Nonetheless, the trend is clear: In the 6.1-year time period, 1,145 black males were killed, compared to 2,993 white males. But don’t be misled by the raw count — when one accounts for overall population size of both demographics, it’s clear black men are at a much higher risk of being killed by police.

“The disparities and risk of killing were so uniform nationally,” Edwards said. “Even in rural places — even in places with relatively small black populations — we still see elevated risk of being killed by police among black people.”

Some regions were far worse than others. In metropolitan areas overall, the median risk of being killed by police was at least 4.3 times greater for black adult males than white adult males. Among Mid-Atlantic metro areas, researchers calculated a median risk ratio of 8.2 black adult males killed by police for every white adult male. (That number was calculated from areas such as New Jersey’s Essex, Hudson and Union counties, New York’s Bronx, Erie, Kings, Monroe, New York, Queens and Richmond counties and Pennsylvania’s Allegheny and Philadelphia counties).

“We are working on another analysis right now that shows black women are also at a high risk of being killed [by police] — at about double the risk of white women,” Edwards said.

The data-driven details

Some might say police had a right or a reason to kill in some of these situations, such as fearing for their lives. But that doesn’t logically explain why black and Latino men are killed by police at higher rates than white men, and to pin it all on the deceased would be acutely racist. Nor does it explain why black men are at higher risk of being killed by police in certain parts of the United States.

For that reason, researchers didn’t make any moral judgements on whether or not police had grounds to kill. Doing so runs the risk of masking greater societal forces like geography and or racial inequality — or just the shocking prevalence of police homicides in the first place. A 2015 study from the Human Rights Analysis Group also came up with high numbers, estimating 10,000 U.S. police homicides occurred between 2003 and 2009, plus in 2011 (including males and females).

“Rather than trying to reduce this to a narrative in which killings are considered justified or not justified, we’re interested in thinking about police killings more generally,” Edwards said.

“It was clear to me that we didn’t have an understanding of basic police killing facts — how prevalent they are, and some of the geographic regions they happen a lot in,” he added. “We hadn’t really established good baselines for what the rates of killing were.”

Many questions still need to be answered. Edwards is currently working on a future study that will more closely look at the lifetime risk of being killed by police among black, white, Latino/Latina, American Indian, Alaskan Native and Asian-Pacific Islander men and women. So far, his research suggests black women are at the highest risk of police homicide, followed generally by Latina women, then American Indian, white and Asian.

There’s also a question of why so many people die during encounters with police, regardless of whether or not it was a homicide. While some were deemed accidents or suicides, a total of 889 women, seven transgender people and 318 children died amid interactions with the police. Edwards did not analyze these numbers, but he did mention a significant portion of child deaths involved car chases.

“There were a disturbing number of children in the dataset — a real disturbing number,” he said. “But again, that’s one of the things that was really valuable about this data. Those deaths were not included anywhere in official data, because they’re not people law enforcement was targeting in arrests.”