A common bacteria spread in hospitals is becoming resistant to some hand sanitizers, study says

The global hand sanitizer market was worth $919 million in 2016. But dousing our hands in these alcohol-based products may not be as effective as we think, according to a new study published in the journal Science Translational Medicine.

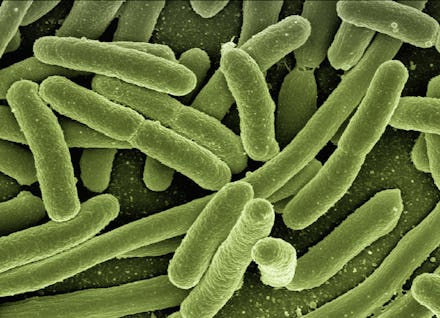

Researchers in Australia gathered 139 different hospital strains of a bacteria called Enterococcus faecium, which is normally found in people’s gastrointestinal tract and is often spread in hospital settings. Researchers studied bacteria samples collected between 1997 and 2015, testing each one to see if they were resistant to alcohol.

The researchers found that the Enterococcus faecium bacteria gathered after 2010 were 10 times more likely to be resistant to alcohol — meaning that they’re incredibly hard to kill with sanitizer. In other words, strains of bacteria from 2010 onward adapted to alcohols used in many commercial sanitizers.

“Anywhere we repeat a procedure over and over and over again, whether it’s in a hospital or at home or anywhere else, you’re giving bacteria an opportunity to adapt, because that’s what they do, they mutate,” Tim Stinear, a professor at the University of Melbourne and the scientific director of the Doherty Applied Microbial Genomics Center, said in a release. “The ones that survive the new environment better then go on to thrive.”

Enterococci bacteria is no joke. It makes up about 10% of hospital-acquired blood bacteria in the world, and is North America’s fourth-leading cause of sepsis (a life-threatening complication to infections), according to the study.

But the lesson here isn’t to stop using hand sanitizer or other alcohol-based cleaners. Instead, doctors, nurses and everyday people should use a variety of products to keep their environments clean — and hopefully, bacteria of the future doesn’t adapt to all of those too.