Dead animals — and their gruesome stories — are the stars of this bizarre museum exhibit

When Amsterdam’s waterways froze over in the spring, canal skaters weren’t the only unusual sight. Just north of the city, 13-year-old Christoph van Ingen stumbled upon a tiny blue kingfisher frozen in canal ice. One Instagram post turned the bird into a viral sensation, and in August, the Natural History Museum Rotterdam opened a special display to preserve the bird in its original block of ice. (I visited the museum in August on a trip organized by the Holland tourism board.)

While this kingfisher has quite a backstory, it’s far from the strangest bird that museum director and ornithologist Kees Moeliker has encountered. Moeliker’s job consists of finding animals with peculiar — and often gruesome — histories for the museum’s popular Dead Animals With a Story exhibit. From a black-headed gull that collided with a helicopter to a pigeon that caused power outages across the northern Netherlands, Moeliker’s seen plenty of rare birds in his 30 years with the museum. But none can top the bird that started it all. On June 5, 1995, Moeliker noticed a live mallard copulating atop a dead mallard outside his office window.

“A duck crashed into our building then landed in the grass; it was raped for 75 minutes by another duck, and what’s really interesting is both of them were of the male sex,” Moeliker said in an interview. “I’m a biologist, and I’ve never seen sex between a dead and live duck — it’s homosexual necrophilia. It was 1995, before the internet, so I had no framework to put this behavior into.”

Completely baffled, Moeliker sat on the experience for six years before publishing his observations in his paper, “The first case of homosexual necrophilia in the mallard.” The paper led to a 2003 Ig Nobel Prize (a program awarding research that makes people laugh then think), followed by a TED Talk in 2013.

“More people got interested in the paper and wanted to see the duck, so we put the duck on display with a sign next to it,” Moeliker said. “Then it started to grow. We found more dead animals with stories, and now it’s one of our main attractions.”

And while one duck inspired the Dead Animals With a Story exhibit that opened in 2013, the collection of taxidermic animals has continued to grow. Here are some of the other highlights.

The sparrow that ruined Domino Day

The “domino sparrow” is a tiny bird that caused enormous controversy on National Domino Day in 2005. Volunteers from all over the world gathered in northern Holland to attempt to break the domino-knocking Guinness World Record, only to have their efforts thwarted when a rogue sparrow knocked over 23,000 of the more than 4 million dominoes arranged for the live TV event. To avoid further damage, a pest control firm shot the bird, sparking commotion and anger. The confiscated body now resides at the Natural History Museum Rotterdam alongside several of the original dominoes.

The political mouse

Further down the display case sits a mouse caught in a trap alongside a 2012 government envelope addressed to Moeliker. The “parliament mouse” was living in the Dutch Parliament’s House of Representatives wing during a major rodent infestation. Moeliker requested a rodent for the museum, but was turned down given parliamentary regulations. He’d almost given up hope until he came home to find an anonymous House of Representatives envelope containing a trapped mouse and nothing else.

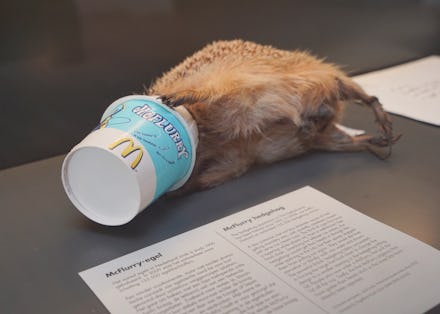

The ice-cream-loving hedgehog

One of the more eye-catching displays is a hedgehog trapped in a McFlurry cup. According to Moeliker, hedgehogs love dairy products, and they often search for leftover ice cream in carelessly tossed ice cream containers. Unfortunately, their spines make it impossible to exit some lids, which was the fate of this McFlurry hedgehog — the Netherlands’ first “McFlurry victim.”

What we can learn from dead animals

One thing Moeliker hopes this exhibit will subtly illustrate is that these animals aren’t simply oddities. They carry a message about human-wildlife coexistence.

For example, the exhibit’s “CERN weasel” found its way into the Large Hadron Collider near Geneva — the largest machine on Earth — in 2016. The small Stone Marten weasel jumped the fence and collided with an 18,000-volt transformer, effectively shutting down the power supply while ending its own life.

“You’ll see sometimes the world of humans and animals collide with dramatic effect,” Moeliker said. “The weasel died — if you look carefully you’ll see it shows signs of electrocution — but the machine also broke for a week.”

In 2011, the Natural History Museum Rotterdam witnessed a disheartening story featuring one of its own dead animals: the rhinoceros. Thieves broke in overnight to steal the stuffed rhino’s ivory horn, and made their way out of the building all within two minutes.

While it’s not technically part of the exhibit, this green-horned rhino is perhaps the most jarring reminder of human-wildlife conflict in the museum.

“It was the first time ever that we had a break in, and they were only after the rhino horns,” Moeliker said. “They broke in, cut the horn and it fell [three stories]. You can still see the scar on the floor. We had it restored, but I thought it still looked too real — we have to make sure they understand it’s fake so that’s why we used green.”

It was a first for the Natural History Museum Rotterdam, but ivory theft is a growing problem for museums around the world. According to the Humane Society International, thieves have stolen horns from a zoo in Germany and a museum in Cape Town. Smithsonian reported that a horn was stolen from the University of Vermont in 2017.

On a global scale, humans and wildlife may struggle to peacefully coexist, but Moeliker said he hopes engaging visitors through stories is the first step. For example, every June 5 — “Dead Duck Day” — Moeliker invites the public to the scene of the duck incident for discussions about preventing bird-window collisions — after reliving that fateful duck-on-duck afternoon, of course.

“With 500,000 dead animals and plants, it’s hard to grab people’s attention for our exhibits,” he said. “If there’s a strong story attached to the specimen, people will pay attention longer than 10 seconds. They’ll remember it, they’ll talk about it and they’ll tell their friends — and it all started here with the duck.”