A Portrait Of the Quintessential Millennial Poet, 24 and in Love

… can our dreamsever blur the intransigent lines which drawthe shape that shuts us in?— Sylvia Plath, "Tale of a Tub" (1956)

The newest book of Sylvia Plath's work showcases not her poetry, but her artwork. Sylvia Plath: Drawings is a slim and elegant book worthy of many a millennial coffee table. It is not only an interesting artifact of the poet who articulated the woes of our time far before we knew them, it is also a beautiful, multi-textured window into that poet's life when she was 24, in love, and at the peak of her life.

Sylvia Plath is the quintessential poet of the millennial experience. Her role as a timeless voice for our generation is bound up with the tragedy and mystique of her life — after all, she killed herself when she was only 31 and so, in memory, remains perpetually young. Her classic confessional novel, The Bell Jar, brutally depicted the way, at the cusp of adulthood, we can be horrifically paralyzed by the prospect of endless possibility, and how that paralysis can turn possibility into decay. The poems on which her reputation rests — published posthumously in Ariel — were written in a frenzy when she was 29 turning 30.

However, few people know that Plath was also an adroit and passionate visual artist. She studied drawing from a young age, and developed a personal style that she described as "a kind of child-like simplifying of each object into design." The detailed ink drawings of everyday objects and scenes in this new book reveal not only the care Plath paid to her surroundings, but also the care she paid to the task of drawing. In a 1956 letter to her fiancé Ted Hughes, she described drawing as a therapeutic meditation: "It gives me such a sense of peace to draw; more than prayer, walks, anything. I can close myself completely in the line, lose myself in it."

Plath had big ambitions for her art — she hoped to publish her drawings alongside her poems one day, "to make a sheaf of detailed stylized small drawings of plants, mail-boxes, little scenes, and send them to the New Yorker which is full of these black-and-white things." In letters she described her drawings with pride, and was ecstatic when the Christian Science Monitor agreed to publish her drawings alongside a series of travel articles, imploring her mother in a letter to "Please get lots and lots of copies of each article. The sketches are very important to me." One can imagine that Plath, multi-talented and ever curious, would be fascinated by the possibilities of artistic multimedia available today.

In 1956, the year the bulk of the drawings and letters collected in Sylvia Plath: Drawings were produced, Plath had just graduated with highest honors from Smith College and was studying at Cambridge on a Fulbright Fellowship. She had just met the poet Ted Hughes, and, in the course of a few months, found herself married to him and honeymooning all over Europe. By then, Plath had overcome the debilitating depression and treatment chronicled in The Bell Jar. 24 and in love, she was bursting with artistic energy and a revived joy in the world.

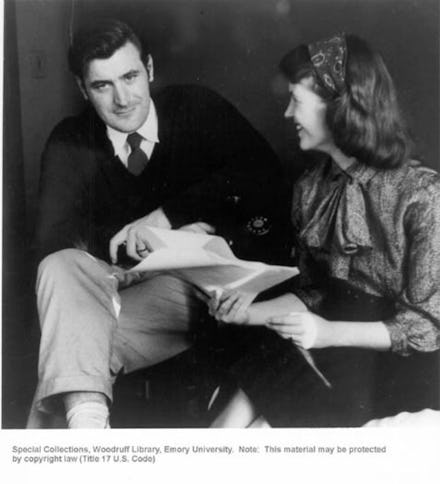

The drawings and letters from this book, first exhibited in London two years ago, are evidence of her creative revival. "Every drawing has in my mind and heart a beautiful association of our sitting together in the hot sun, Ted reading, writing poems, or just talking with me," Plath wrote in a letter to her mother, "… how creative Ted's made me!" She describes her idyllic days as a newlywed: "I … went about with Ted doing detailed pen-and-ink sketches while he sat at my side and read, wrote, or just meditated. He loves to go with me while I sketch and is very pleased with my drawings and sudden return to sketching." The pages of this book brim with evidence of the young marriage's creative dynamism.

The poignant and effusive meeting of hearts and minds preserved here is only more precious in light of what we know will become of the marriage — that it will dissolve under Hughes' infidelity, and ultimately catalyze the mental decline that led to Plath's death.

Still, Drawings is comforting. Taken alongside her poems from the time, the book shows how our beloved poet worked attentively in many artistic registers to elaborate the beauties of everyday life. After Sylvia Plath: Drawings, it will be impossible to read the lines from "Song for a Summer's Day" — "I saw slow flocked cows move / White hulks on their day's cruising; / Sweet grass sprang for their grazing" — without thinking of Plath taking out her sketch paper and plopping "in the long green grass amid cow dung" to draw. The 1956 poem "Ode to Ted," when placed beside her dark and chaotic pen sketch of her husband, becomes something else entirely. So, too, do her lovingly drawn thistles and flowers illuminate the emotion behind the first stanza of "Southern Sunrise":

"Color of lemon, mango, peach, /

These storybook villas /

Still dream behind /

Shutters, their balconies /

Fine as hand — /

Made lace, or a leaf-and-flower pen-sketch."

Drawing, like poetry, opened up new worlds for Plath. "It is as if, by concentrating on the 'inscape'," she wrote, "… of leaf and plant and animal, I can know the world a new and special way; and make up my own version of it." Likewise, this book of Plath's drawings opens up new worlds for the interpretation and enjoyment of her poetry.