What the Silk Road Shut Down Means For the Future Of Free-Market Capitalism

When Silk Road, the encrypted online marketplace, was shut down by the FBI on Wednesday, October 2, the drug trafficking underworld erupted into chaos. One user posted, “I shoulda stocked up on LSD and DMT.” Another began manufacturing commemorative ecstasy pills imprinted with the site’s logo. Bitcoin, the digital currency used by the site, lost over 16% of its value in about an hour, and there was talk that Tor, the encrypted platform used by sites such as Silk Road, had been compromised.

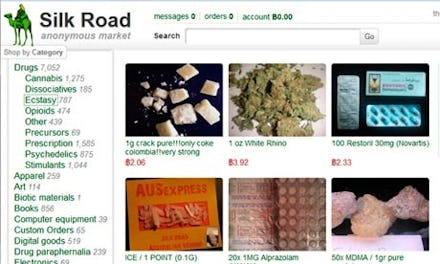

Yet this wasn’t just an operation against one local gang – the site was a billion dollar industry with reaches around the world and with roots in American drug and cryptology cultures. Drugs aren’t part of any abstract underground culture, and neither was Silk Road. There were around 960,000 individual accounts on the site, and over 1.2 million transactions were made in the site's two-and-a-half years of operation.

While Silk Road was an ultimately flawed project, the site gave us a look into the future of free-market capitalism. Silk Road revealed the potential of decentralized online marketplaces to circumvent federal laws, especially taxation, regulatory, and drug laws. Although the shutdown of Silk Road is a step back for the free-market movement, the system itself is constantly growing and advancing. Despite its shortcomings, Silk Could could serve as a model for the future expansion of the movement. And at the end of the day, it may actually benefit the movement that Silk Road's founder, Ross Ulbricht (a.k.a. the Dread Pirate Roberts), wound up getting caught.

The testimony of FBI special agent Christopher Tarbell to the Southern District of New York, states that in an attempt to shut down the site, FBI agents had to discover the real identity of the Dread Pirate. However, since the Dread Pirate used Tor to log in to his site, he was “practically impossible to trace.”

Nevertheless, Ulbricht left his guard down and made several crucial mistakes, such as posting his real email on the website he used to advertise Silk Road, and going to a nearby cybercafé in San Francisco to log in to his account. This news was a relief to Tor users – the system was still unbreakable – only human mistakes could ground it.

It is clear that Ulbricht's site has ties to the free-market movement, which uses encryption to promote anarchist principles. However, Ulbritch clearly did not abide by the movement's rejection of the “systemic use of force.”

There is evidence that Ulbricht at least once solicited the services of a hitman on Silk Road in order to knock off a vendor on the site who was threatening to release the real-world addresses of thousands of users. Although the plot seems to have been a ploy by Silk Road users, Ulbricht clearly violated the free-market movement's commitment to non-violence. The site also violated free-market principles by selling falsified documents.

But Ulbricht appears to have lived up to certain free-market principles. For example, he refused to sell child porn and counterfeit currency. As for the charges of money laundering leveled against the site, Silk Road was actually very transparent in what it offered to users.

Whatever the outcome of the case against Ulbricht, Silk Road will be remembered for blazing the trail for online marketplaces. Its users will not go away; similar sites, although currently less reliable and principled, are already popping up. Ulbricht’s declaration that “we’ve won the State’s War on Drugs” will become a reality when 100 new Silk Roads appear. And based on Silk Road's success, that day could come sooner than you think.