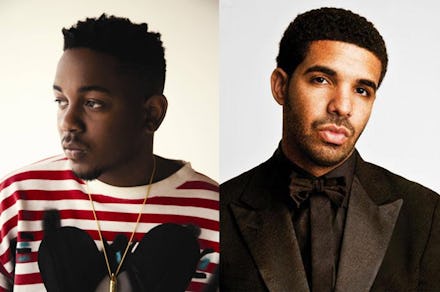

The Kendrick Lamar and Drake Feud is Bringing Hip Hop Back to Life

That epic high-five was heard around the world last week at the BET Awards. Kendrick called Drake into the ring during the TDE cypher and delivered this line: "And nothing been the same since they cut 'Control' and tucked a sensitive rapper back in his pajama clothes / HA HA, jokes on you! High-five!" And with that momentous slap, we saw a rivalry spark between two kings again.

This is not another modern rap beef. Potshots are not being traded on Twitter. We're not seeing scrums outside the club — those messes fade fast. This is long-term, dynasty-building stuff. It will play out on the charts, in the number of classic albums, singles, and number of features stolen. Kendrick Lamar vs. Drake is the most compelling rivalry since Tupac and Notorious B.I.G.'s East vs. West fight in the 90s. The music Kendrick and Drake make is radically different though, mainly because our times have changed and they speak to new audiences. The new kings of hip hop are attuned to the millennial experience in a way that delivers an emotional impact that most recent hip hop music has been unable to provide. Kendrick and Drake have the skills, sounds, and stories to capture their listeners' experiences with that necessary mastery that hasn't appeared since the old gods of the genre lost relevance. The course of their rivalry will shape the direction of hip hop in the years to come.

Kendrick Lamar and Drake's music display a new level of introspection and emotional understanding that resonates with millennials. The themes of their music stretch outside the well-worn gangster-fresh pathways that the old gods paved. Every gangster story on Kendrick's good kid m.A.A.d. city comes with an accompanying emotional analysis. In "Art of Peer Pressure," Kendrick contrasts the happy-go-lucky "big ballin' with my homies" narrative with deeper concerns: "I never was a gang-banger, I mean I was never stranger to the four neither/ I really doubt it / Rush a nigga quick and then we laugh about it / That's ironic 'cause I've never been violent, until I'm with the homies." These moments of introspection provide new meaning for the mob mentality of hip hop's hood games, something that social commentators have been trying to penetrate for years. Our generation's mainstream culture has a sympathy for the hood experience that was somewhat absent in previous generations. We don't buy into the idealistic prospect of social mobility as much as other generations. Kendrick's music taps into this millennial sympathy, and offers a very complete understanding of the causes and effects of poverty and the gang-banging lifestyle.

The narrative possibilities for hip hop are opening up as younger generations are becoming more receptive to rap as a form. Because the genre reaches a wider audience now, the message is shifting and should continue to shift. Hip hop is no longer only for those starting at the bottom. Drake has done a lot to make hip hop more accessible to those who never had a ghetto experience. His music offers the kind of emotional candor many express in social media. In a recent interview, Drake described his aims: "I use rap music to talk about my life ... My songs are status updates." Millennials respond to those more mundane introspections for the same reason we check our social media handles daily. We are interested in how others are feeling about life. In a way, we have a new tolerance for the mundane. Lyrics like "I needed to hear that shit, I hate when you're submissive / Passive aggressive when we're textin', I feel the distance" (Drake's "From Time") show this especially clearly. Who in the world has never received a passive aggressive text? It's a common millennial experience, and one hip hop is well-suited to address.

No one else in hip hop right now is poised to redefine the genre and gain kingship status like Drake and Kendrick Lamar. Jay-Z's time has come and gone. Kanye is more focused on being a god than being a relatable human being, and so his music will never again have the ability to resonate with millennials like Kendrick's and Drake's. How can millennials feel like gods? We have rock bottom employment rates. The man that the majority of us elected to create hope in Washington is powerless. The new kings of hip hop need to speak to these insecurities and complexities. The only two that can and will are Drake and Kendrick Lamar.

By tapping Drake as a rival for the top, Kendrick has brought some much needed fire back to hip hop. With the wide audience they both have gained, they can change the perceptions of what hip hop can be. Self-proclaimed old-school hip hop faithfuls may never accept Drake's music because its emotional sensitivity does not fit the common rapper mold, but, with 12 number one singles and three number one albums, he's making it hard to be disrespectful. Maybe one day hip hop won't be characterized solely by misogyny, stunted emotional content, and violence. Perhaps it will be characterized for its its ability to capture real emotion and real experience. Kendrick and Drake have work to do.