Why I Hid My Chinese Name

On Sunday, the Smithsonian National Zoo announced that it had named its newborn panda cub "Bao Bao," which means "precious" or "treasure" in Chinese. The revelation came with its fair share of fanfare, as hundreds of visitors attended the naming ceremony and multiple media outlets shared the news.

But these naming fesitivites were marked by irony. While panda lovers across the country have celebrated Bao Bao's Chinese name, the reality is that few seem to understand the cultural significance of this milestone.

Like stereotypical "black" names, Chinese names are heavily stigmatized in the U.S., seen as silly, unpronouncable, even un-American. The "black name dilemma," as New York Times contributor Nikisia Drayton calls it, reflects the fact that we have collectively created and collectively sustain unfair, fictitious and racialized portrayals of people whose names aren't "mainstream" (read: white). A name like Shaniqua, for example, is commonly seen as "ghetto," even though the name itself says nothing about the character of the person who bears it. Similarly, Chinese names evoke Oriental "exoticness," which is in reality no more than a figment of America's imagination.

Some people have taken this a step further and misappropriated or satirized Chinese names, as if they have no inherent cultural value. (You can even use a fake Chinese name generator to come up with your own.)

In July, the Oakland news station KTVU aired a segment on the Asiana flight crash, identifying the pilots with four fake "Chinese" names. The names were allegedly an internal joke not meant to air, but that didn't stop KTVU from purportedly checking how to pronounce them with an editor who bore a real Chinese name.

Screen shot courtesy of Salon.

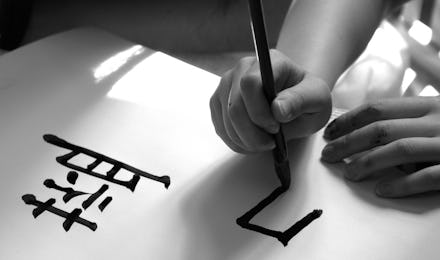

I know personally what effect these kinds of "jokes" have. My middle name is Yuting, which means "serving one's country" in Chinese.

My parents decided that my Chinese name would be my official middle name to remind me of my heritage. To them, it was a sign of cultural pride; to me, an unnecessary burden.

When I was young, I tried my best to hide it from my friends. I wasn't ashamed of having a Chinese name per se, but I also didn't want to be made fun of for not having an English middle name. Most of my friends, both Chinese and non-Chinese, had common American middle names like Sophia, Victor and James. I didn't. My friends and classmates would pester me to reveal my Chinese name, but I steadfastly refused. At times, what seemed like a simple request would turn into a mock-playful, at turns disrespectful, conversation about what my Chinese name could be.

"What is it?" one colleague asked. "Is it Ping Pong or something?"

"You know how Chinese parents name their kids, right?" someone jokingly asked me one day. "They drop a spoon on the floor and whatever sound it makes is that kid's name."

These offhand remarks only strengthened my resolve to keep my middle name a secret. I knew if I chose to reveal it, I would be confronted by even more ignorance. I had heard people make fun of immigrants with Chinese names, and I didn't want to be confused for one.

Moreover, I had already been dealing with incessant jokes about my last name because I shared it with none other than action movie star Jackie Chan.

"Do you know kung fu?" my friends would ask; I'd respond by smiling sarcastically and walking away. My Chinese surname had given me enough troubles. I didn't need to exacerbate the problem by revealing my middle name.

My struggle to identify with my Chinese name has persisted for years. Although my middle name is a constant reminder of my heritage, my parents and friends have remarked on occasion that I seem out of touch with Chinese culture.

Sometimes, I find it difficult to argue otherwise. I was born in New York and grew up in Forest Hills, a predominantly Jewish neighborhood where Chinese families used to reside in small numbers. Despite attending Chinese school for much of my childhood, I rarely spoke Cantonese with my parents. Most of my closest friends were Jewish and Hispanic, so I never felt the need to share my Chineseness with them. I was always under the impression that doing so would make me the "other," like the immigrants who failed to assimilate into American society, and who were mocked for doing so.

I'm not wrong to feel that way. Like the jokers at KTVU, insensitive people still use Chinese-sounding names to poke fun at East Asian accents. I have occasionally heard people poke fun at Chinese immigrants and say their names are all "fwied wice," an insulting nod to the Chinese inability to pronounce the letter "r."

While incidents like the KTVU broadcast and popular memes about East Asian accents can feel like a smack across my face, I have slowly learned to dismiss them as petty. My Chinese name is who I am. The stigma that Americans attach to it doesn't define me.