Dead Man Talking: How Deceased Heroes Become Political Props

If George Washington, Abraham Lincoln, and Martin Luther King, Jr. were alive today, they would all agree that what I'm about to say is important.

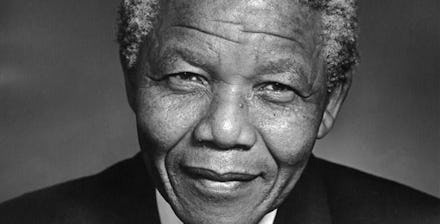

I've written elsewhere on the lines already formed in the battle over Nelson Mandela's legacy, but there is a subset of this fight that deserves attention on its own, and which carries a special generational responsibility for those of us who will, some day, be the last living people who can recall the former South African president as he actually was: We cannot, however tempting it may be, start invoking Mandela every time we want to lend moral weight to an argument.

It's a bad habit of ours. When an icon dies and their stature is so great that nobody within the mainstream can afford to disparage them, a kind of consensus forms, whereby the content of the dead leader's heroism is replaced with the vague notion that they stood for "justice," "freedom," and "peace." Rather than remember what the words meant to those leaders, we imagine they would support whatever those words mean to us. Slowly but surely, the icon is erased, and we end up in a world where today's young reactionaries really believe that King would be backing "right to work" laws and voting Republican were he alive today, because those are the things they consider to embody justice — and justice, undefined, is what they learned King stood for.

Of course, with the more recently dead, it almost feels reasonable: we could, with some critical thinking, imagine how King or Gandhi, or even a Roosevelt might respond to present conditions. But extended over the long lens of history, the idea of teleporting old heroes to conditions that would fundamentally alter who they were, pretending we know what they might want, becomes an exercise in absurdity. We get members of Congress, convinced they know what the Founding Fathers would think about guns in a world of police, telephones, and streetlights; sentences like "John Locke would have said…" are uttered with a straight face in some dispute over post-industrial fiat monetary policy.

Can we all agree that if Thomas Jefferson had been born in the first century AD and had been named Augustus, he would've been Caesar? As Winston Churchill would say, "Give me a fucking break."

With Mandela, this pattern has already begun, most notably with Rick Santorum's ludicrous comparison of apartheid with Obamacare.

But the tendency to abuse the dead in this way isn't limited to the Right. It's something all ends of the political spectrum do when they've run out of real arguments and need the false weight of some dead hero to lend credence to their cause. But more often that not, the effort just comes out contrived; worse, every phony claim makes the cited name carry a little less weight, until "such and such would have said" has no more gravity than "I like this and you should too."

The practice isn't just ludicrous; in the end, it's self-defeating.

Yet there's greater cause to break this bad habit than avoiding shitty strategy. When we hold up famous names like talisman in debate, we don't just weaken our own arguments; we destroy the very legacy that made the names so notable in the first place. Mandela did not become synonymous with justice because he spoke in broad, popular platitudes; he did so because he devoted his life to fighting a terrible and specific instance of systemic injustice in the form of South Africa's brutally racist apartheid regime. A regime, mind you, that was supported by many of the same conservatives now mourning Mandela in the abstract.

When we start placing Mandela in ever more improbable hypotheticals, we allow the world to forget that fact. We allow the world to slowly disregard what Mandela, when he was alive, actually said and wanted. If there's a more disrespectful or ironic way to undermine the very cause that won him our devotion, I can't think of it.

Mandela said that systems of brutal racist oppression must be fought with all available means, and that "overcoming poverty is not a task of charity, it is an act of justice."

He didn't and never will have anything to say about some petty political battle 20 years from now. Let's promise that we won't pretend he did, for his sake, and for our own.