Which American English Do You Speak? This Map Shows the Dialects Of the USA

Finally, a map that explains the complex reasons you're probably not pronouncing "chowder" right, and why we should all start saying "y'all."

As much as the United States may be unified by/ export its popular culture, American culture is actually an amalgamation of numerous ethnic and historical influences.

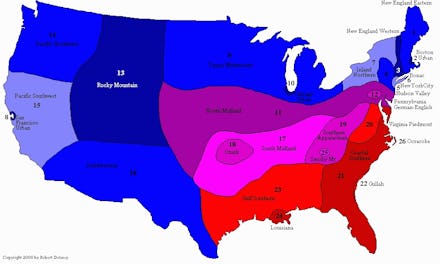

The below map, created by Long Island University reference associate and library webmaster Robert Delaney, is designed to show the considerable linguistic diversity of the United States, which shapes both the way that we communicate and the discourses that we have.

In the map, which is based on the book Success With Words: A Guide to the American Language, Delaney divides the country into three main dialect groups: General Northern in blue, Midland in purple, and General Southern in red. Those groups, in turn, contain 25 regional dialects, each of which has a distinct accent, lexicon, and grammar.

(If you want to see where your accent falls, try pronouncing the list of words found here.)

Delaney’s work makes several things apparent. The map shows that linguistic groupings clearly have little to do with the administrative divisions that we’re so used to seeing imposed on the map, as cultural divisions transcend state lines, as in the sprawling, Scandinavian-influenced Upper Midwestern area. In fact, distant areas can have more in common linguistically than the regions between them. The “General Northern” region stretches across the Canadian border and down the West Coast, pointing toward the fact that California and the Maine have more in common linguistically than they do with, say, the Gulf Coast.

When it comes to individual dialects, geography plays an important role in isolating and dividing populations. While large bodies of water seem to have little effect — the location of the Mississippi River, for instance, isn’t at all evident — mountains often play a role in creating distinct language groups.

While Appalachia is well known for its distinct culture, Delaney identifies a 30-by-60 mile are of the Smoky Mountains as containing uniquely “archaic features in its pronunciation, vocabulary, and grammar.” The Ozarks are similarly divided from the Pennsylvania Dutch and Scotch Irish inflected South Midland area.

While some of Delaney’s dialects span several states, he identifies a number of American cities as having prominent local speech patterns.

New Yorkers and Bostonians have long been mocked for their thick local accents, both of which are prone to dropping the letter R, much as Chicagoans are known for their love of Da Bears. However, Delaney identifies the San Francisco Bay Area as distinct from surrounding Northern California thanks to the accents of the Midwesterners and Easterners who have flocked there over the years.

Historical cultural migrations are also responsible for some of the smaller linguistic blobs on the map, as in the South, where not all drawls are created the same. In Louisiana, the influence of French-speaking Acadian settlers resulted in Cajun culture, and the Southeast Atlantic coast, where descendants of slaves from disparate regions of Africa speak Gullah.

Delaney points out that further linguistic divisions are, of course, possible. Immigrants bring their own accents, and patois, to the cities in which they settle. And even native speakers in individual cities can have highly distinct accents. In New Orleans, for instance, you can hear multiple accents, from the lower- and middle-class white “Yat” (which is oddly similar to Broolynese), to the highfalutin enunciation of the uptown white population, to the dialect of the African American community, each of which defines the cultural and class background of the speaker. Which is not even to address the wide regional variations in African American Vernacular English.

While Americans may be shaped by different cultural influences, speak different dialects, and have distinct political leanings, our expansive country still has plenty of room for discourse. More attention should be paid to how we communicate, and the importance of cooperating across cultural boundaries — whether or not you say “pop” or “soda,” and no matter how you pronounce the word “lawyer.”