Presidential Pardons Expose Just How Screwed Up Our Justice System Really Is

On the heels of President Obama's Thanksgiving-day turkey pardon, he came under fire from the left for not using his pardoning powers more often.

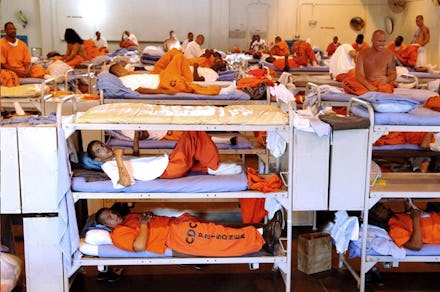

Proponents of increased pardons would have the President use his constitutional power to address problems with the justice system to compensate for a do-nothing Congress. However, presidential pardons are a drop in the ocean compared to the level of reform our justice system really needs. Not only that, but more than anything, they're indicative of a fundamental problem in our justice system: unfair treatment.

As examples from Obama’s predecessors illustrate, pardons often benefit the politically connected, not the systemically slighted masses. Obama has pardoned 40 inmates to Bush's 99 and Clinton's 77 (in their first six years of office). This compared to the millions of Americans, who aren't politically connected, that are sitting in jail for non violent offenses.

Towards the end of George Bush’s presidency, he was flooded with requests for pardons from close friends. In his memoir he writes, "I came to see massive injustice in the system. If you had connections to the president, you could insert your case into the last minute feeding frenzy." Bush decided that all pardons, no matter who lobbied for them, would receive regular Justice Department review.

Despite Bush’s policy, Dick Cheney put a full court press on Bush to pardon former vice presidential aide Scooter Libby over the advice of the White House legal team. Bush held his line and went with the recommendation of his lawyers over the pleadings of his deputy to pardon Libby.

Where Cheney failed with Bush, Marc Rich succeeded. The late hedge fund manager and commodities trader whose personal lawyer was a top aide to both Bill Clinton and Al Gore leveraged his connection to lobby for a pardon from Bill Clinton for his convictions of tax evasion and oil dealing with Iran during the Iranian hostage crises. On his last day in office, Clinton obliged and issued a pardon.

In the ensuing media hoopla, it was revealed that Rich’s wife made a significant donation to the Clinton library. The situation surrounding the pardon was so controversial that Clinton took to the New York Times op-ed page to defend his pardon after leaving office. Though noted legal academics agreed with the pardon, (in a strange coincidence he cited “Republican attorney” Scooter Libby in his defense) there was no talking around the financial benefits of his decision.

These two anecdotes illustrate the importance of personal and political nature of the pardoning process. Those with connections to the White House get their story heard, and those without are on their own. Prison reform is the kind of systemic problems better solved by legislation, not unilateral actions from the President that only benefit the few.