The American Dream is Dead in the South

The entire premise of the American Dream is that if you work hard, your life, or your childrens' lives, will be better. It's the promise that has brought immigrants to these shores for centuries, and it's the most frequently-touted line by Republicans who oppose social safety nets. If you have good ideas and you work hard, the logic goes, then you can lift yourself up by the bootstrap and move up in the world.

But it seems we may have definitive proof that the idea of upward mobility is a myth — in certain parts of the country, at least.

Researchers at Harvard have released a new study showing that while the income gap is as wide as ever, there is still some chance for those at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder to climb up. The study analyzed various social factors — parent/child income, college attendance, teenage birth — and calculated the likelihood of a child from the bottom 20% of the economy working up to the top 20%.

But while the national average of economic mobility was a low 7.8%, the most shocking thing that the researchers found was the wide discrepancy among states and researchers: "[I]n some places, such as Salt Lake City and San Jose, the chance of moving from the bottom fifth to the top fifth is as high as 12.9%. In others, such as Charlotte and Indianapolis, it is as low as 4.4%."

The sharp difference in upward mobility in different regions led the researchers to conclude, "The U.S. is better described as a collection of societies, some of which are 'lands of opportunity' with high rates of mobility across generations, and others in which few children escape poverty."

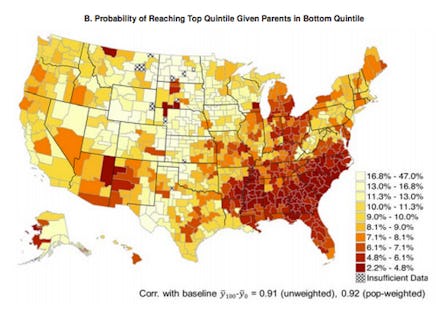

Matthew O'Brien at the Atlantic posted a handy graph illustrating this regional divide:

As shown in the map, the areas with the worst upward mobility chances are disproportionately concentrated in the South and around Ohio. But what makes certain states so unnurturing towards the American Dream?

The biggest factor that the study points out is race. But while "intergenerational mobility is lower in areas with larger African-American populations," the study found that this is true of both white and African-American families who live in heavily black neighborhoods. "Such segregation could potentially aff ect both low-income whites and blacks, as racial segregation is often associated with income segregation," the study concludes.

Other important socioeconomic factors discussed in the study are income, local public goods and tax policies, the quality of schools and access to higher education, the availability of jobs, migration rates, the strength of social networks and community organizations and the stability of family structures. These factors give credence to what we already intuitively know: kids from stable families and well-off communities with lots of resources are more likely to do well.

Thus the South, with its heavily segregated neighborhoods, low income and low figures for high school and college graduation, does not provide a conducive environment for young people who are trying to better their circumstances. (Ohio also has three of the most segregated cities in the U.S.)

Maybe those who love "rags to riches" stories can keep this graph in mind the next time they want to extol the virtues of individual work and reward. While the idea is certainly appealing, the myth of bootstrapping prevents our society from identifying and fixing the systemic failures that oppress those who are at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder with little help or recourse.