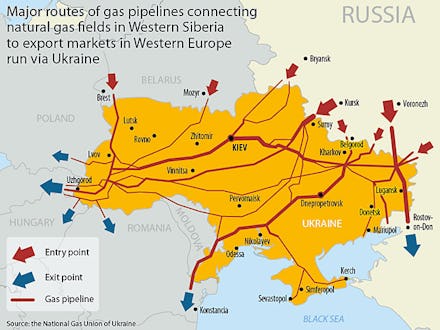

To Understand What's Really Happening in Ukraine, Follow the Gas Lines on This Map

Shocking no one, Russia's top natural gas producer, Gazprom, announced last Tuesday that it will cancel a discount on the price it charges for gas in Ukraine.

The bargain, a sweet 30% off the price of gas, was a bid by Moscow to deter Ukraine from accepting a trade deal with the EU.

"This is not linked to politics or anything," Russian President Vladimir Putin told reporters on Tuesday, regarding the discount cancellation.

The ongoing Ukraine crisis is often cast as a battle of values, East versus West. But another way of looking at things is to follow the old gas lines.

In a nutshell:

Ukraine would freeze without Russia.

Some 60% of Ukraine's consumed gas comes from Russia. Over the years this reliance has given rise to a so-called gas "mafia" in Kyiv. Ukrainian oligarchs, working closely with Russian suppliers, have taken advantage of the dependency. It is widely believe that these elites siphon money from state coffers and actively prevent Ukraine from developing a sustainable energy sector. All the while, foreign investors are scared away.

Similarly, Russian energy supplies help Moscow to keep a firm grip on other former Soviet states like Moldova and Georgia. In September Russia's Deputy Prime Minister Dmitry Rogozin threatened to cut off Moldova's gas supply during the winter if the country continued on its pro-EU economic course. "We hope," said Rogozin to Moldavians, "that you will not freeze."

Europe is hooked too.

Russia supplies, but Ukraine is the middleman. This helps to explain why some European states (like Germany) have been cagey about imposing sanctions on Russia. Germany and Ukraine are Gazprom's biggest foreign purchasers.

Russia is Europe's largest natural gas supplier, supplying about one-third of the continent's natural gas, more than half of which travels through Ukraine. Important pipelines pass through Ukraine to Slovakia, and then on to Germany, Italy and Austria.

So, what would happen if Russia switched off the Ukrainian pipes? Actually it has done just that twice over the last decade, in 2006 and again in 2009, amid pricing disputes between Kyiv and Moscow. The result: gas shortages in several European countries.

Already Europe is working to wean itself off Russian supplies. Ukraine's woes might help to speed up that process.

It's a two-way street.

Russia needs Europe too. Oil and gas trade accounts for half of Russia's annual export revenue and more than half of Russia's federal budget.

Important to note is that many of Russia's important gas pipelines go through Western Ukraine, which is decidedly pro-Europe.

"I would argue that Russia has more to lose than Europe at the moment," says Tim Boersma of the Brookings Institution. "Russia needs European demands. It is making roughly $100 million a day from hydrocarbons.

What about America?

Washington is making moves. The U.S. doesn't export natural gas yet. But congressional Republicans especially are calling to loosen U.S. export restrictions, with the idea that if Washington puts more gas on the market, it can (economically) cut Russia down to size.

The U.S. Department of Energy is issuing permits to American corporations that will let them start exporting gas in 2015.

Fun fact: Who is now leading the U.S. State Department's new Bureau of Energy Resources? It's Carlos Pascual, former U.S. ambassador to Ukraine.

So what about that new global order?

In recent weeks Eurasia experts and political hacks have been talking big about a new global energy order inspired by events in Ukraine.

Chaos in Ukraine, goes this logic, will threaten natural gas supplies and push Europe to look for non-Russian gas sources.

It's already happening. U.S. energy behemoth Halliburton Co. will soon start fracking in Poland. Royal Dutch Shell will start hunting for natural gas in Ukraine next year.

In fact, Europe is already way less energy-dependent on Russia than it was in 2009, the last time Moscow switched off the Ukrainian pipelines. Germany, for instance, has found alternative energy sources in Norway and Algeria.

2009 was a turning point. And 2014 could be Russia's biggest mistake yet.