80,000 Americans Suffer From a Cruel and Unusual Practice Most Countries Abolished

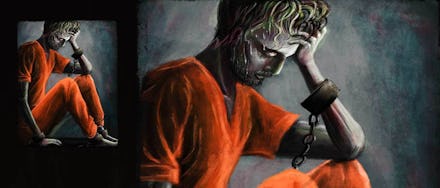

You jolt awake from a disturbed sleep, your body dripping with sweat. You don't know how much time has passed — minutes, hours, perhaps even days. But you feel frightened, and your heart is racing. You had a nightmare. You were in a dark, narrow, endless hallway. You were chasing a young man, shouting to him, but no sound came out. You had to warn him of something — you don't know what. He stopped walking and slowly turned around. You noticed his shoes, the tattoos on his arms. He was you — a younger you. His body was filled out, healthy, like yours used to be. His wrists weren't shackled. But you couldn't quite make out his face. You inched closer, squinting. But he had no face at all; there was just a blank blur. He did not recognize you, either. He turned back around and kept walking.

That's when you woke. Now tears are coming down your face. Maybe it wasn't even a nightmare. In fact, you might've not been asleep at all.

This is your existence in "the box." You live in your brain, inside a cage, inside a penitentiary — a prison within a prison within a prison. The cell itself is smaller than 8 feet by 10 feet, about the size of a bathroom. It’s impossible to walk more than a few steps in any direction. You've paced it hundreds of times, counting five tiles per step. You've memorized those dirty, cold tiles: every crack, every imperfect angle. You've studied them backwards, forwards and sideways. Sometimes you watch the cracks deepen, bend, or shift. Occasionally a roach or a mouse scurries past. You like when they do … a life to watch, something to talk to.

Above is a low ceiling. Around you: three concrete walls. The dark grey paint is chipping away, revealing traces of past occupants — the stains of old graffiti, carvings of initials and marks where fingernails once scratched, scraped, dragged and dug. Then there’s the door: a heavy slab of steel. It never opens.

Thus completes the anatomy of the hole in which you dwell, the cage that contains you, the chamber that chokes you.

There is no window; there is no clock. The artificial light is on at all times. You don't know what time it is, what day or month it is. Time can stretch into endless vacuity, collapse abruptly, or warp into itself — a nasty little trick.

You notice that the rusty faucet in the corner is dripping. The rhythm is heinous and quickly becoming unbearable. Drip... Drip…. With each drop, your intestines twist tighter, your chest sinks heavier. It's insufferable. It has to stop. An insect flies by. The buzzing vibrates through your ears, mildly, at first. But within seconds, it intensifies, grips your skull, climbing inside and infecting your brain with rapid reverberations. The insect is inside your head now. It's certain. And still, the dripping water is getting louder and louder. It's deafening. The piercing sound of each drop, the rattling of the bones of your skull — you can't breathe. You yank violently, viciously at your hair, shrieking between stifled gasps.

But no one hears you. No one cares. And you have nowhere to go.

***

This depiction is fictional — but just barely. It's based on detailed accounts from prisoners who were held in isolation, and drawn from psychological studies that document the horrific symptoms that inmates commonly battle when held in solitary confinement — the practice of isolating inmates in closed cells.

The U.S. has less than 5% of the world's population, but 25% of the world's incarcerated population. The country's prison population has increased by 700% in the last 30 years, exceeding 2 million people in 2002. Prisons are now 40% over capacity and account for a full quarter of the Department of Justice's budget. Half of federal inmates are serving time for drug-related offences, the majority of which involve marijuana.

Craig Haney, a professor of psychology at the University of California Santa Cruz, has been studying the psychological effects of prison, specifically solitary confinement, for about 30 years. Broadly speaking, incarceration has both punitive and rehabilitative purposes, but where the emphasis falls "makes a huge difference." Over the last three decades, we've "abandoned our commitment to rehabilitation," he said, noting a distinction: "A person should be sent to prison as punishment, not for punishment." Countries that have placed heavy emphasis on rehabilitation have significantly lower rates of recidivism.

A person should be sent to prison as punishment, not for punishment.

While the number of incarcerated persons has skyrocketed over the past few decades, the amount of prison space has not expanded to accommodate it. To make matters worse, as stated in a New Yorker piece, "Work and education programs have been cancelled, out of a belief that the pursuit of rehabilitation is pointless. The result has been unprecedented overcrowding, along with unprecedented idleness — a nice formula for violence."

Solitary confinement was always around, but only as a last resort, employed for short periods of time. Now, it's used as "an immediate fix to a complex problem," Haney said. The practice has been largely discontinued in most countries, but the opposite has happened in the U.S. where it's become routine. This is despite the call of a UN expert on torture for all countries to ban solitary confinement of prisoners except in "very exceptional circumstances and for as short a time as possible, with an absolute prohibition in the case of juveniles and people with mental disabilities."

Solitary confinement involves isolating inmates in cells which are hardly larger than a king-sized bed for 22-24 hours per day. It can last anywhere from days to decades. Inmates rarely have a window or see any sunlight, and there is an artificial light on 24 hours a day.

There are three types of solitary: disciplinary, for violating a prison rule; protective custody for vulnerable persons, such as LGBT and juveniles; and administrative segregation, known as "AdSeg," based on classification rather than behavior. For example, an inmate might be held in AdSeg while prison officials try to determine his or her role in a fight, or if he or she is a danger to others (most commonly by participating in a prison gang.)

There is a common misconception that solitary is strictly reserved for violent felons who are a danger to other inmates. But it's actually being widely overused as a punishment for minor disciplinary violations while in prison, such as ignoring orders or using profanity. According to the Washington Post, in New York, there are roughly 3,800 inmates in solitary confinement for "violating prison rules."

The 2000 census estimated that there were over 81,000 inmates in some form of isolation in the U.S. — roughly the total number of all prisoners in the whole of the U.K. This number does not include juvenile facilities, immigrant detention centers or local jails. People in solitary confinement constitute 7% of all federal inmates. One-third to one-half is mentally ill, and a disproportionate number are minorities.

Prolonged isolation causes severe mental and neurological damage. Humans are fundamentally and intrinsically social beings. We depend upon each other and rely on interaction in order to function normally and identify and place ourselves in the world. The New Republic wrote, "Psychobiologists can now show that loneliness sends misleading hormonal signals, rejiggers the molecules on genes that govern behavior, and wrenches a new slew of other systems out of whack." They noted that emotional isolation is ranked as high a risk factor for mortality as smoking is. Brain scans reveal that people without sustained social interaction have become as impaired as people who had incurred traumatic brain injury.

Image Credit: AP

Typical symptoms of a person in solitary include: hypersensitivity to external stimuli, hallucinations, panic attacks, cognitive deficits, obsessive thinking, paranoia, anxiety, nervousness and anger. Boston psychiatrist Stuart Grassian wrote that, "Severe restriction of environmental and social stimulation has a profoundly deleterious effect on mental functioning. … Even a few days of solitary confinement will predictably shift the EEG pattern towards an abnormal pattern characteristic of stupor and delirium." Inability to focus attention or shift attention is commonly observed; a minor bodily sensation can grow into an all-consuming life threatening illness; ordinary stimuli can become intensely unpleasant; and small irritations can easily become maddening.

Autopsies reveal that the brain of someone held in solitary has a shrunken hippocampus, the neural region responsible for forming and retaining memories, and regulating spatial recognition and orientation. Also, the lack of sunlight can be a critical driver of depression. The severe damage to circadian rhythm can be observed in brain autopsies of inmates who committed suicide.

About half of prison suicides happen in solitary confinement, although inmates in solitary make up less than 10% of the prison population.

A U.S. military study of about 150 naval aviators who returned from imprisonment in Vietnam revealed that they found the social isolation to be as agonizing as any physical torture they endured. Sen. John McCain was a prisoner of war in Vietnam for five years, two of which were spent in solitary confinement. He has said that solitary "crushes your spirit and weakens your resistance more effectively than any other form of mistreatment." And this is coming from a man, as a New Yorker author wrote, who "was beaten regularly; denied adequate medical treatment for two broken arms, a broken leg, and chronic dysentery; and tortured to the point of having an arm broken again."

***

Five Mualimm-ak, 38, was convicted of assault on police officers, trafficking and drug possession. He was sent to Auburn Correctional Facility in New York in 2006 or 2007 — he doesn't remember exactly. He was sentenced to 33 years to life.

He was put in "the box" because of a disciplinary violation, he said. The charge: He had too many pencils and stamps in his possession. When he first entered solitary, he said, it was a "huge emotional moment," because they threw away a lot of his property. He was given three pairs of underwear, three pairs of socks and a jumpsuit.

One disciplinary ticket gave way to another, the days mounted, and his time in solitary expanded from 90 days into a miserable five-year stretch. "You’ve been removed from the society that you’ve been removed from," he said, sounding like he still could not make sense of it.

He did not commit one act of violence during his time in prison, he said. Once, out of starvation, he ate an entire apple, including the core and seeds. But since apple seeds contain arsenic, inmates are prohibited from eating them, as outlined in the handbook. He received another ticket, more days in solitary. The next time he got an apple, he did not eat it out of fear that he'd be written up again. So he got a ticket for "refusal to eat." Once, when he put his arm through the slit in the door for the nurse to give him his diabetes shot, she yanked at his arm, and out of instinct, he jerked it back. Another ticket: refusal of medical care.

First, he noticed the sensory deprivation. "As the months go on and the days turn into weeks, you don’t know what time it is and what day it is. … You start to imagine things. Then all your senses start to be bombarded," he said. "You have no control over it; you cannot stop. It’s just invading your brain and how you make sense of it."

The days and nights melted and stretched. He counted the tiles on the floor, stared at the ceiling, read the dictionary, re-read it, re-wrote it, re-wrote it backwards. "But what do you do after that? Well, you start talking to yourself. … Then, you end up speaking inside your head."

"Then, of course, it comes to the point … because I want you to understand … validation. Without that validation … it made me angry. It made me upset." In an article for the Guardian that he wrote after his release, he said, "The very essence of life … is human contact, and the affirmation of existence that comes with it." Without it, "You become nothing." He wrote, "I was so lonely that I hallucinated words coming out of the wind. … I often found myself wondering if an event I was recollecting had happened that morning or days before." He feared that the guards would come in and kill him, leave him hanging dead. "Who would know if something happened to me? … I was invisible."

In our interview, he said he had only two things during his time in solitary: his memory and his imagination. "But how does a person know that they are not going crazy?" At a certain point, he didn’t know if his memories were real or not. He couldn’t remember what his children looked like.

"You just sit there. You just rot." He would sleep for days and weeks on end.

Throughout our conversation, his thoughts would stray, come back suddenly, or jump somewhere else. "Even now, I have memory …" He trailed off before drifting to another thought.

Image Credit: Wikimedia Commons

***

Solitary confinement is not only cruel, but it is also ineffective, wasteful and dangerous for society. It is highly unlikely to change the inmate's behavior for the better. And multiple studies have shown that removing a member or two from the general prison population does not change its overall level of violence.

The daily cost for an inmate in solitary is roughly $120, whereas it’s $70 for a general population inmate. Nationally, it’s estimated that the average cost to taxpayers to keep an inmate in solitary for one year costs $75,000.

The practice also poses risks to society. About 95% of people held in solitary will eventually return to the world. Mental illness will have developed or exacerbated, and there's a higher chance of recidivism. It's a dangerous, senseless cycle.

The good news, as Haney said, is that the issue is receiving an "unprecedented amount of attention lately" and "finally a heightened awareness." Our interpretation of the Eighth Amendment — which prohibits cruel and unusual punishment — is an "evolving understanding." The public is "just becoming aware of the magnitude" of this problem and he is hopeful that it will reach the Supreme Court in the next five years.

On Feb. 19, New York State corrections officials of the New York State prison system agreed to new guidelines that limit the maximum duration of solitary confinement and curb the use of solitary for vulnerable populations. Inmates under 18 will receive at least five hours of exercise and other programming outside of their cells five days per week. This makes New York the largest prison system to end the most extreme form of isolation for juveniles.

Sen. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) recently argued that humane treatment of prisoners is a human rights issue to be tackled seriously and urgently. In a Feb. 25 statement to United States Senate Committee on the Judiciary Legislative committee, he said, "Congress has been able to find common ground on many important issues. But criminal justice reform is one area where we can show the American people that their government still functions. … By reforming our solitary confinement practices, the Unites States can protect human rights, improve public safety, and be more fiscally responsible. It is the right and smart thing to do, and the American people deserve no less."

Image Credit: AP

***

Five Mualimm-ak was released from prison on Jan. 15, 2012. He was released directly from solitary confinement to the bus stop on Manhattan's 42nd street. (According to New York Civil Liberties Union, nearly 2,000 people in New York are released directly from extreme isolation to the streets each year, without any educational, vocational, rehabilitative or transitional programming.)

Crowds of hurried New Yorkers surrounded him. "My heart started racing. I was having a panic attack." A homeless man approached him and said, "Oh, you just came home. You’ll be alright."

Mualimm-ak was homeless until a couple of months ago. Because of his criminal record, he could not get a job or live in public housing. Now, he's back on his feet, working as the program director for End the New Jim Crow, a grassroots campaign to change mass incarceration and prison practices. "I couldn’t get out and not do nothing," he said.

Looking back on his time in solitary will always be painful for him. "People say, 'Ooh, I’m a survivor of solitary.' That's not true. Nobody is a survivor of solitary. [The question is] what level of deterioration you have. ... I never survived."

But that doesn't mean he's not fighting every day. He's raising the public awareness needed to create the change that he and so many others deserve.

***

Tweet me with questions or thoughts @lauradimon.