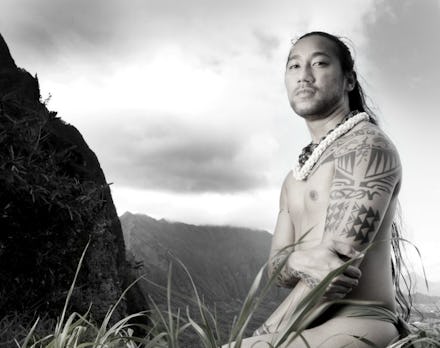

These Photos Are Challenging Notions of What an American Indian Really Looks Like

"Where’s your horse? Would you bless me? I’ve always wanted to be blessed by an Indian."

These are the types of questions photographer Matika Wilbur, a member of the Swinomish and Tulalip tribes, has encountered when meeting non-Native people. Such experiences have largely prompted her latest endeavor, Project 562. Wilbur, whose name means "messenger," wants to use her photography to deliver a powerful message about what it means to be Indian. As a Native from the Lumbee tribe, I find her project to be a refreshing and much-needed wake up call.

"I was always the only Indian in art school," Wilbur told PolicyMic. "Even in public school I didn’t have an American Indian teacher. We’re largely unrepresented."

After graduating and becoming a teacher herself, Wilbur began noticing the ways misunderstandings about contemporary Indian identity have become ingrained in mainstream American culture.

"I would be asked about blood quantum: 'Well, how much of an Indian are you?'" she said. "As if I should prove my pedigree like some dog. Or people would ask why I didn’t speak a language and I would have to explain the actions of the federal government and cultural appropriation that led to us leaving that behind."

Wilbur's mission to document each of the over 560 federally recognized tribes across the United States and tell their stories is equally important today as when she was growing up. In the past few years alone, there have been countless instances of American ignorance when it comes to indigenous issues. One glaring example is the ongoing debate over the Washington Redskins: Passionate football fan or not, many Native Americans consider the name "Redskins" antiquated at best, if not an outright racial slur.

Then there's the practice of redface, which stereotypes Native peoples. Redface gained the spotlight with Johnny Depp's film flop The Lone Ranger. Depp’s Tonto character came across as a caricature, raising some interesting questions as to why a real American Indian actor wasn’t cast in the role.

You may also have noticed redface at your last Halloween party. Sorry, but there's no way donning war paint or a headress and picking up a tomahawk doesn't create a racist and vicious caricature. In fact, the headdress is considered a sacred item, so wearing it for the sake of being fashion forward is a slap in the face to Native culture.

Throughout her travels, Wilbur said she has also encountered numerous health care problems among Native people. High rates of diabetes, alcoholism and suicide continue to plague indigenous communities. Meanwhile, between 2005 and 2009, American Indian males had the highest rates of suicide of all the racial and ethnic groups. Exacerbating matters are the high levels of poverty and emotional abuse Native people face on reservations.

Wilbur admits she doesn’t have all the answers to fixing America's problematic relationship with indigenous peoples just yet. But there are ways to facilitate change on a smaller scale, this photo project being one of them.

"People often ask me why I don’t photograph real Indians," Wilbur told the New York Times recently. "But the people that I photograph are real Indians. These are my people."