Here's the Essay That Got One Teen Accepted Into Every Ivy League School

This 17-year-old's application essay got him into all eight Ivy League schools — despite a declining acceptance rate in seven out of eight Ivies and an era of increased selectivity in elite educational institutions.

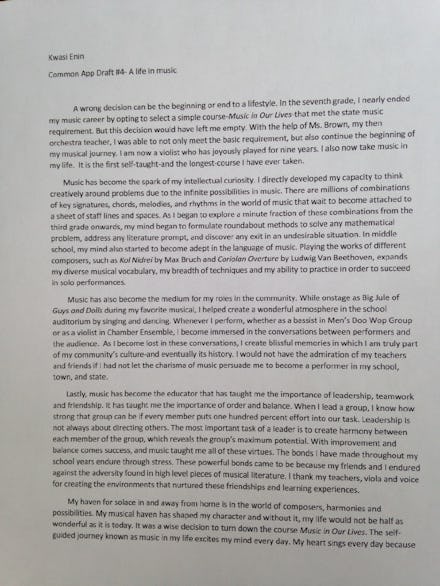

What exactly did Long Island high school student Kwasi Enin, who has straight As and a 2,250 SAT score, write? The New York Post obtained a copy (readable below), and as New York Mag observes, "It is very much a college essay — flowery language, Big Ideas, lessons learned — but it also worked."

"Music has become the spark of my intellectual curiosity," Enin wrote. "I directly developed my capacity to think creatively around problems due to the infinite possibilities in music."

"My haven for solace in and away from home is in the world of composers, harmonies and possibilities. My musical haven has shaped my character and without it, my life would not be half as wonderful as it is today."

Image Credit: William Floyd School District

It's a well developed, by-the-numbers essay, and it's easy to tell why it was such a hit with the Ivies' admissions department. It perfectly played to the expectations and demands of self-proclaimed elite schools (without going overboard like this dude), and it's way better than what most high school seniors could produce, so kudos to a well deserved hit by Enin. (As for the haters, of which Thought Catalog anecdotally found a few, well ... tough beans.)

But for all the praise Enin is getting for acing the essay, NY Mag has a point when it asks: "Why do we make kids do this to themselves?" It's pretty hard to demand even bright young scholars to humble-brag about their accomplishments to pedigree-obsessed institutions without in some way denigrating the educational value of a degree. This is a real problem acknowledged by many in the college industry. Writes eHow's Dave Roos:

"The increasing selectivity of the Ivy League admissions process only exacerbates the problem, creating hordes of Ivy-obsessed students who place unhealthy pressure on themselves to be accepted.The danger of the brand-name, "bumper-sticker" mentality is that an Ivy League education is being sold as a product rather than a valuable experience. And students, in a desperate attempt to obtain that product at any cost, sometimes turn the application process into a marketing campaign, or worse, a business."

For every amazing success like Enin, there's a minimum of 84.85% of applications that get rejected from an Ivy — for Harvard, it's 93.28%. Even the extremely well vetted don't always make the cut. Take Sam Werner of Norwalk, Conn., who was rejected from both Stanford and Princeton in 2008 despite perfect SAT scores, membership on two sports teams and ranking third in his class. A 2012 Princeton-conducted study of 10,6500 students and parents found that 71% of respondents gauged their stress levels during the process as "high" or "very high," which is up 15% from 2003.

And this stress isn't necessarily correlated to a school's quality of education. The 2013 edition of the study found that 51% of the respondents' main priority in college selection was a "potentially better job and higher income," and just 24% saw education as the primary benefit. The most stressful part of the process was "completing applications for admission and financial aid," said 34%, and both parents and students are increasingly worried about how college will impact a student's "career interests."

"College admission is how a lot of people are defining success these days," said Dr. Denise Pope, who founded the Challenge Success group (admittedly, at Stanford) in 2008. "We want to challenge people to achieve the healthier form of success, which is about character, well-being, physical and mental health and true engagement with learning."

Of course, finding a good job and a stable future is an indisputably important factor to consider in an admissions process. But the primary advantage of an Ivy degree is exactly what students and parents report they're looking for: connections, connections, connections. Sociologist Lauren Rivera says that "elite professional service employers" (think Wall Street, law firms, and consultancies) rely more on academic pedigree than pretty much anything else when hiring, including how Ivy students spent their time at those institutions. (A notable exception is extracurriculars that "resonate with white, upper-middle-class culture," like lacrosse and crew, because these send signals to elite employers that the prospective employee will fit right in.)

The result in the hiring process for elite jobs — which, again, parents and students self-report as extremely important when selecting colleges — is this, Rivera writes:

"Successful candidates therefore needed to possess enough cultural breadth to establish similarities with any professional with whom they were paired, but also enough depth in white, upper-middle-class cultural signals to relate to and excite their overwhelmingly white, upper-middle-class, Ivy League-educated interviewers."Mastering this is ... "not only a prerequisite for admission to America's most elite colleges, but also for entry to its highest paying entry-level jobs."

So when talking about the Ivies, remember that it acts in many ways as a filter and regulator for entry to a very specific kind of social class. And an awful lot of students are stressing themselves out for an unlikely entry to this world, when they might be better served looking for colleges that are a good fit for them and what they actually want in a career and life after college.

In the end, even those that make it through the process might found out an elite job won't make them particularly happy in the first place.

None of this is to denigrate or take away from Enin's astounding achievements, which probably make us all a little jealous. But as he enters this elite world, he should think very frankly about what he'll use the incredible access he's rightfully gained to achieve — both for him and others.