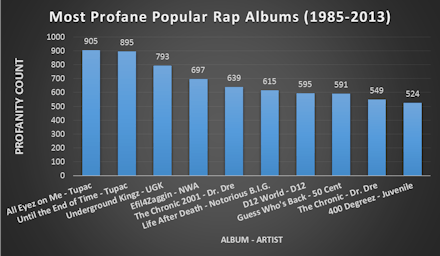

This Chart Shows the Most Popular, Dirtiest Rap Albums in History

Rap music is far and away the most graphic and controversial style of music that has ever graced the ears of listeners. And now, thanks to the researchers over at Best Tickets Blog (and the writers at Pigeons & Planes), we have a definitive list of which albums teenagers should turn to if they really want to freak their parents out.

Image Credit: Best Tickets Blog

Researchers over at Best Tickets Blog recently compiled the most profane of popular rap albums. They analyzed five of the most influential albums from each year of 29 years of rap history, and found that across those 145 albums, listeners have heard a total of 31,564 curses (or 217.7 swears per album).

But a strange trend emerged from the data: As it turns out, the most profane albums on the list were also clearly the best. Though all examined were influential, the density of swears on an album seems to correlate pretty well with its importance.

Take N.W.A., for example. They had a particularly important role in shaping the history of rap profanity: They popularized the use of the n-word. Before the group hit the scene in the late '80s/early '90s, the word had only appeared in a handful of songs. However, after 1991, when Niggaz4life was released, the "average n*gga frequency" never dropped below two occurrences per song.

It sounds like a joke, but that was actually a breakthrough for hip-hop. The lyrics off the album's title track, "Niggaz 4 Life," are structured to address the group's incessant cursing. The song opens with a bunch of audio clips of critics reacting to N.W.A.'s use of the word "n*gga": "Why you brothers insist on usin the word nigga? ... Don't you know that's bringin down the black race?"

Each one of the members of the group starts their verse addressing the question "Why do I call myself a nigga, you ask me?" before tearing it up with some of the most famous verses in rap history.

MC Ren reels in with: "Well it's because motherfuckers wanna blast me / And run me outta my neighborhood / And label me as a dope dealer yo, and say that I'm no good."

And then Dr. Dre follows him with: "I guess it's just the way shit has to be / Back when I was young gettin a job was murder / Fuck flippin burgers, cause I deserve a / Nine-to-five I can be proud of, that I can speak loud of / And to help a nigga get out of."

So curses aren't just curses, then: They're the only effective way to represent the frustration, outrage and inequality inherent in the black man's position in the American ghetto. It's no coincidence that the list's most profane album, Tupac's All Eyez On Me, is also one of the greatest hip-hop albums ever made. When Pac rapped "I'm movin you stupid bitches, vicious telekinesis / Am I reachin your brain?" he knew full well how many swears "vicious telekinesis" required.

But for a long time, swears in hip-hop have been seen as something shameful. Rev. Al Sharpton led one of the biggest, most publicized protests against the use of profanity in rap with his "March for Decency" in New York back in May 2007. He described his aims at a press conference: "I think it is important that we make a strong appeal as consumers to demand standards that will not offend us or dehumanize us based on race, gender or any other category."

But all real rappers knew that he was missing the point. Jay-Z, king of kings, called him out on his song "Say Hello":

"And if Al Sharpton is speaking for me,

He knew well that imagining rap music without curses is as difficult as imagining impoverished areas with fully outfitted public schools. It's doubtful that sanitizing the language of rap would help public school funding come faster — actually, aid might come more slowly if there weren't a cultural sense of urgency surrounding it.

That urgency exists because rappers like Tupac hadn't forced our culture to listen by making the kind of bold statements that Sharpton wants to get rid of. If those statements were anesthetized, they would never have been heard. Profanity isn't just anger. It's a key to the art's social significance.