This 3-Minute Video Reveals the Surprising Link Between Hip-Hop and Better Schools

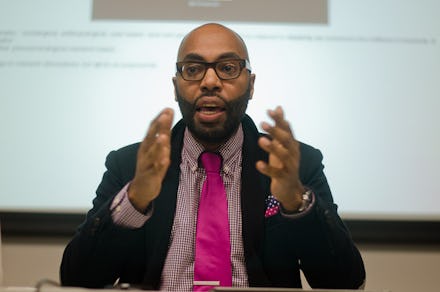

Dr. Christopher Emdin isn't your average Columbia University math and science professor. Not that I'd know.

But the renowned educator and public speaker certainly has a novel approach to teaching. When discussing the so-called "culture gap" that divides teachers from their students, he says a major problem lies in how teachers are trained to present information.

"Right now," he explains in an engaging TED Talk, "there is an aspiring teacher, in a graduate school of education, who's watching a professor babble on and on and on about engagement — in the most disengaging way possible." Anyone who's sat through a chemistry lecture knows what he's talking about.

So what's the medicine for these babbling teacher drones? How can "magic" be re-introduced into the classroom? According to Emdin, the answer lies in three specific cultural spaces: hip-hop, barbershops and the black church.

And the result is something like this:

Well, damn. So how did this awesome-ness come about? It stems from a relatively simple concept, and here's where Emdin breaks it down:

Put simply, the key to holding an audience "rapt with attention," sitting at the edge of their seats waiting breathlessly for your next words, is to become a compelling storyteller. No shit, right?

But this skill is not born, it's taught. Emdin's main example is the call-and-response theatrics of preachers, who use a combination of rhythm, volume control and audience involvement to draw listeners and engage them with information. Barbershop banter and the ability of rap artists to galvanize crowds are other examples of "master teachers" at work. Emdin argues that public school educators need to study these people, and use their tools to better communicate lessons to their students.

"The folks who know the skills about how to teach and engage an audience don't even know what 'teacher certification' means," he says.

Emdin is especially vocal about STEM (science, technology, engineering and mathematics) education. It's widely documented how lacking these subjects are in both students and teachers of color — namely black Americans and Latinos — a fact that can be attributed to multiple interlocking factors, including societal "discouragement." That these kids are disproportionately targeted for disciplinary action doesn't help their prospects either.

Image Credit: Teachers College, Columbia University

But much of this disparity is linked to cultural gaps between educators and their students. "For a large number of minority youth and women, STEM has been what I'd describe as 'Eminem-ed,'" writes Emdin in a New York Times op-ed. "Basically, a white male face represents STEM, and the inherent patriarchy and bias perpetuated by gatekeepers in STEM goes unchallenged."

The National Educational Association reports that 76% of new teachers confirm their training covers diverse students, but only 39% said this training was "helpful."

"STEM instruction should be rooted in the art and culture of marginalized groups," adds Emdin. "To make STEM more fun and accessible, students must see themselves as inherently scientific, and their worlds as naturally mathematical."

So how do you do this? Emdin's flagship example is Science Genius B.A.T.T.L.E.S., a joint education effort with GZA of the Wu-Tang Clan. The program is designed to teach STEM subjects using hip-hop, and mainly targets the black and Latino students who comprise 70% of New York City's student body:

"This is a response to achievement gaps in science and mathematics," says Emdin. "It is a response to students' disinterest in science, and more broadly to kids just not wanting to show up in school."

The program has grad students from Teachers College, Columbia University, helping kids compose and develop "science raps," which showcase the different STEM theories and principles they've learned. Students then compete in end-of-semester "battles," which are judged by GZA and published on Rap Genius.

"To make STEM more fun and accessible," writes Emdin, we must "expand" it "to include youth who are most ostracized from these disciplines. The chief way to do this is to meet them on their own cultural turf."

It's an exciting approach to teaching, and one that hopefully yields long-term results. Full disclosure: I suck at science — but this makes me want to give it another chance.