Japanese Youth Are Taking Their Love of "Black Culture" to an Insane New Level

"Pale skin is a symbol of beauty in Japan," states Metropolis TV reporter Mao. "That is why Japanese girls hate the sun. But nowadays not all girls hate it. They want dark skin, so they look like American hip-hoppers."

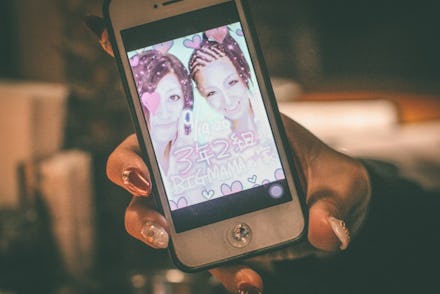

So begins a report examining "B-style," a Japanese youth subculture whose love for all things "black" prompts devotees to braid their hair, rock "urban" fashion and routinely darken their skin at tanning salons.

According to VICE, many of these young women and men work at Baby Shop, a fashion boutique nestled in a popular Tokyo mall. The store slogan is "Black for Life." They hang out bars like Shibuya and Yataya, both alleged "meeting place[s] for hip-hop dancers, rappers and clubbers," and often dress up for "adventurous black night[s]" on the town.

"Black people look so great and stylish," says Hina, a Baby Shop employee and focal point of both reports. "When we wear [certain things] it looks vulgar, but not with black people." The video for 50 Cent's "Candy Shop" plays on her iPad as she speaks.

Hina's mother views her daughter's lifestyle as a fad: "Sooner or later it will get boring," she says. "When you are young you can do these things, so I say, do what you want."

Yet while B-style adherents view their steez as a "tribute" to blackness, the way they express it speaks volumes to how culture gets commodified and exported on a global scale. Many will defend them by claiming their contemporary brand of "blackface" is inoffensive because it's meant as a compliment. Admiration breeds emulation, so what's the issue? This argument misses the point.

While their collective intentions appear innocuous and maybe even flattering, the deeper problem lies with the concept that blackness can be performed. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, blackface was part of a multi-faceted cultural machine designed to affirm and justify the degradation of black Americans. By performing blackness as caricature, whites divorced black people from their individuality and humanity, framing them as inherently dull-witted, salacious and generally inferior. Such performativity retains its cruel power today because of a simple fact: Social inequality along racial lines still pervades American society. It is no bygone relic. It is happening now.

Image Credit: VICE

What complicates this situation is that Japanese youth have little context for the troubling history of minstrelsy that plagues the U.S. and Europe, and the reification of white supremacist constructs that accompanies it. But they don't live in a vacuum either. That B-style even exists as a subculture proves that a specific type of "blackness" is being marketed to the world, one rooted in hip-hop and sold through an American media machine that has little interest in promoting other iterations of black life. And why would it? Hip-hop sells, and that's what entertainment industry decision-makers care about. Their notorious lack of diversity speaks poorly to this changing anytime soon.

But it bears repeating that there are many other ways to "be black," even if they're not being packaged and shared with the world. That Japanese youth would latch onto and emulate a culture they think is "cool" makes sense. Their seeing it as part of a monolithic representation of "blackness," however, is a failure rooted in the U.S. This needs to change. As long as racial representations are tied to such narrow definitions, there's plenty of work to be done. And the problem, in this case, isn't Japanese. It starts right here at home.