A "Human Zoo" Is Opening in Norway, in the Name of Art

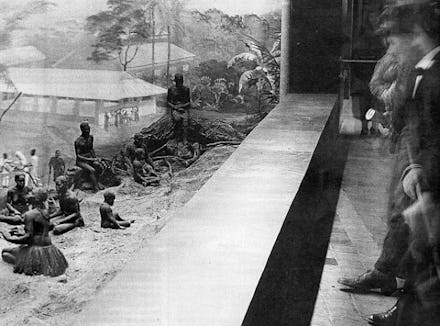

Some of the biggest cultural touchstones from a century ago still live on: the Titanic, the first crossword puzzle, the lead-up to World War I. But there are other equally important touchstones that we have forgotten about today. That's the case in Norway, where most citizens are learning for the first time that in 1914, Oslo was home to a "human zoo" in which 80 people lived for five months in "the Congo Village" surrounded by "indigenous African artifacts."

At a time when only 2 million people lived in Norway, 1.4 million saw the exhibit. That most Norwegians know nothing about this today intrigued artists Mohamed Ali Fadlabi and Lars Cuzner, who decided to recreate the human zoo for its 100th anniversary next month.

The outrage was immediate, and the project, which is funded in part by the government as public art, has been denounced as shock theater by the left and the right. Fadlabi and Cuzner warn prospective village volunteers that they will be asked to defend their participation to individuals, the media and the world. In a country that consistently outperforms virtually everyone else in happiness ratings, quality of life and other indices, it is undeniably bizarre that anyone would propose something so blatantly against national values of tolerance, equality and human rights.

But a closer look at the project's goals paints a more complex picture that Fadlabi and Cuzner hope to call into question. A conference in February, which they organized, held talks entitled "The Terrible Beauty of Hindsight," "Racism Embedded in the System" and "The Origins of the 'Regime of Goodness.'" The artists' statement asks how an entire country could become so ignorant of its own unpleasant past, and then pushes further: "How do we confront a neglected aspect of the past that still contributes to our present?"

Furthermore, the artists propose that the very impulses that brought the human zoo to Oslo in 1914 are still governing the way Norwegians think about race and nationality, albeit in a less overt way:

"Human zoos were in general seen as giving important educational experiences, and the Oslo human zoo in particular played a key role in an exhibition that marked an important stage in the building of the national identity. The specific Nordic national branding has come to include the promotion of a people that are not only naturally good but also more tolerant and liberal than most. When quantifying humanitarian goodness the paradox is inherent in the advancement, how can anyone be equal to the most equal?"

Fadlabi and Cuzner see a Europe that is increasingly in the throes of nationalism, xenophobia and Islamophobia. They claim, however, that there are not enough conversations about the root causes of these problems, or about how our own efforts to absolve ourselves of the past impede real dialogue. By staging a reminder of a time when Norwegians literally thought people from Africa were on equal standing with animals from Africa, this new human zoo asks a simple and crucial question: Is this really what it takes to get us to talk honestly about race?