Brad Pitt's New Movie About the Steubenville Rape Has a Strong Message For Men

The video is as ominous as its creator intended — a figure shrouded in a cheap Guy Fawkes mask, his viage illuminated by the glow of a computer screen. Recorded a few nights before Christmas, that digital missive — created by a scrawny young man from Kansas named Deric Lostutter — would set in motion one of hacktivist group Anonymous' highest-profile crusades to date targeting those associated with the Steubenville rape case.

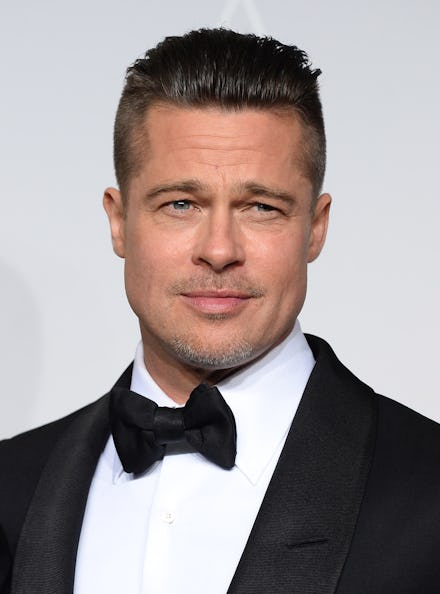

This scene, part of a Rolling Stone article detailing Anonymous's vigilante efforts to expose the Steubenville rapists, may soon be heading to a movie theater near you thanks to Brad Pitt and his production company, Plan B, which bought the rights to the story earlier this month. So far, it seems Lostutter will be the focus of the planned film, though it remains to be seen whether he will be portrayed as a hero or simply the protagonist.

The film has so far met with a good deal of controversy from those who argue the victim — not hackers — should be the protagonist of such a story. While this argument makes sense, a high-profile movie about a high-profile case of sexual assault and could spark a much-needed conversation about the responsibility of men in terms of eradicating rape culture.

And that's a good thing. Because whatever your stance on Lostutter's methods, he is an example of a guy who took action on an issue too often met with silence by men.

All too often it seems, sexual assault prevention is still viewed as a "women's issue," one men appear reluctant to actively get involved with. Sure, when questioned, most men are going to declare themselves anti-rape, but saying you're against sexual assault is like saying that you're "anti-genocide" or "pro-ice cream" — of course you are. Being anti-sexual assault should be a given, not grounds for praise.

The perception that rape is somehow a "women's issue" also assumes that men are never sexually assaulted, when in fact, according to the Rape, Abuse and Incest National Network (RAINN), at least 10% of reported American sexual assault survivors are men.

So what is keeping men on the sidelines? Many, it can be assumed, want to help but are unsure how to get involved. This, however, is no longer good enough. As Jackson Katz says in his excellent TED Talk, "Violence Against Women – It's a Men's Issue," "caring deeply is not enough."

So what can guys do to help prevent sexual assault?

Incidents like the recently leaked email exchanges originating from the underground Epsilon Iota fraternity at American University remind us that misogynistic, hyper-masculine norms still permeate our culture. A CALL TO MEN co-founder Tony Porter and award-winning speaker and educator Keith Edwards often use a box as a metaphor for the way American society currently defines masculinity. This man box has consequences.

Aggression, stoicism, rationality, sexual competitiveness, superiority to women, heterosexuality, lack of vulnerability — these are all some of the ingrained traits expected of men that culturally and emotionally limit them and can degrade women.

"Interacting with men who are feeling insecure and who get messages that proving their manhood is often about sexual conquest affects relationships with women at best and leads to sexual and other violence at worst," Edwards notes.

Image Credit: Keith Edwards

Thus, one important action for preventing sexual assault is challenging the confines of the man box, both for yourself and the other men in your life. Even small things like language can have an impact; for example, be careful not to use degrading terms like "plowing" when talking about a sexual experience, don't mock your buddy when he gets emotional, and don’t use phrases that equate homosexuality or femininity with inferiority (e.g. "You throw like a girl" or using "this is gay" to denote something disagreeable). These little actions may seem insignificant at the time, but they are all part of an effort to be a good ally and a good "bystander."

Indeed, "bystander intervention" programs are becoming increasingly popular on college campuses around the country — and what's more, they appear to be working. The basic premise of these programs is that if you see signs of potential sexual assault, you should intervene. (A recent article in the New York Times prescribes some creative ways of doing so). Such programs aim to make the term "interventionist" as ubiquitous as "designated driver," mirroring the success of Mothers Against Drunk Driving in the '80s.

In the purest sense, Lostutter was a bystander who intervened — and now Hollywood has decided his intervention is worthy of a movie. Again, while the debatable ethics of his methods are beyond the scope of this article, another week's headlines full of fresh high-profile sexual assaults should serve as a reminder that there's still much to be done to amend a culture that facilitates rape and makes the legal and recovery process difficult for survivors.

We as young men have a responsibility to do more than simply say we don't agree with sexual assault — we can be good bystanders, we can educate ourselves and our friends about challenging the man box and we can be good allies for the survivors in our lives (because there is at least one, whether or not you know about it).

We can act. And hopefully, by the time the Steubenville vs. Anonymous movie comes out, we will be able to look back on the incident as a call to action that helped set off a major cultural shift — not a blip in an increasingly dispiriting status quo.