"Hood Disease" Is Everything Wrong With How We Talk About Inner City Youth

The news: Do you live in the inner city? Is your life defined by high stress, malnourishment and random acts of violence?

If you answered "yes," you may be suffering from a dangerous new affliction: "Hood Disease" — or as it's known when applied to white people and war veterans, Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD).

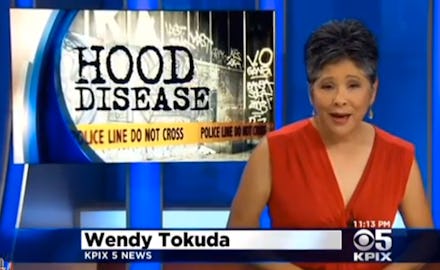

Seriously? CBS San Francisco aired the above report last week. In her segment, correspondent Wendy Tokuda tries explaining how inner city children are subjected to "repeated trauma" from living in "virtual war zones."

"Unlike soldiers," she said. "Children in the inner city never leave the combat zone."

She described their plight through testimony from East Oakland public school teachers, who've noticed some troubling patterns in their students' recent behavior:

"These cards that they're suddenly wearing around their neck that say 'rest in peace,'" teacher Jasmene Miranda told CBS. "Some kids are walking around with six of them. Laminated cards that are tributes to their slain friends."

Image Credit: AP

The facts: The concentration of violent crime in East Oakland is a special point of emphasis. According to the segment, the city's public schools experienced 47 recorded lockdowns in 2013, while East Oakland neighborhoods accounted for two-thirds of the city's murders, with 59.

This violence is wreaking psychological havoc on children: "It's depression, it's stress, it's withdrawals, it's denial," said teacher Jaliza Collins.

The science: Jeff Duncan-Adrade of San Francisco State University describes how this impacts school performance in particular: "You could take anyone who is experiencing the symptoms of PTSD and the things that we are currently emphasizing in school will fall of their radar," he said. "Because it frankly does not matter in our biology … if we don't survive the walk home."

Dr. Howard Spivak of the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) affirmed this when he described a new wave of research at a 2012 Congressional briefing, showing that "American children living in high-crime urban neighborhoods" exhibit higher rates of PTSD than U.S. soldiers deployed for combat in Iraq and Afghanistan.

Image Credit: AP

What it does: In addition to having "serious mental [and physical] health consequences," this disorder can cause hindered brain development, shortened life expectancy and "a range of chronic illnesses, including heart and lung disease and diabetes."

But CBS adds something strange to their report: They claim "Harvard doctors" have classified the ailment as an even "more complex form of PTSD," which some have taken to calling "hood disease."

Why "hood disease"? Wendy Tokuda has since explained her use of the phrase: "I so regret using the term 'Hood Disease' which is not a term either the CDC uses or HARVARD," she explained in an email to EBONY. "That came from a resident in Oakland, and we seized on it. It is my fault."

The name the media has bestowed is one thing. But it's also unclear how this form of the disorder differs from others, and many have raised valid concerns about how differentiating it might impact its treatment.

Son of Baldwin – a race, sexuality and politics blog – said it best when asking why PTSD needs a "colloquial" title now that it's being applied to poor, black and Latino populations. Here's another: How might characterizing it as "hood"-specific "diminish" the seriousness with which people take it? Will the name and its implications be used to conflate its symptoms with other "cultural pathologies" that dominate narratives around the inner city?

Where's Paul Ryan when you need him?

A "preventable disease." The good news is that treating violence as a public health issue places greater emphasis on its root causes, possibly leading to more effective treatments. But the bad news is nothing to sneeze at: The inner city's very existence stems from intentional policies – from racial segregation to redlining to the War on Drugs – that are a living testament to how little our government cares about these areas and their residents.

Is "hood disease" just another way of sweeping "hood problems" under the metaphorical rug? Hopefully not — but when it comes to the inner city, American history has given us little reason for hope.