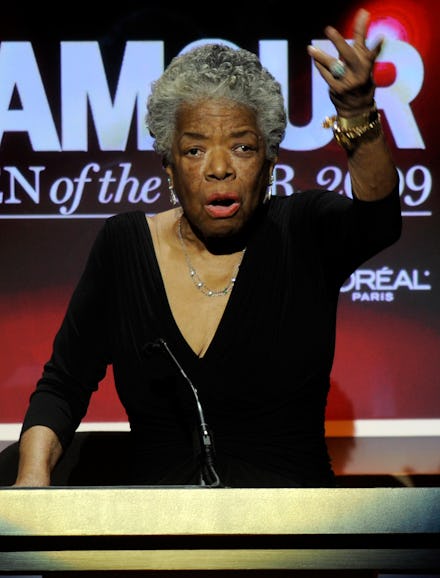

What Maya Angelou's Past Can Teach the Feminists of the Future

Maya Angelou, the author and poet who was an icon for the civil rights and feminist movements, died on Wednesday in her North Carolina home.

An icon embraced by both women's rights groups and civil rights champions, the beloved 86-year-old luminary will be remembered for many milestones — the release of her first memoir, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, in 1969; her friendships with Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X; delivering the inaugural poem at Bill Clinton's swearing-in ceremony in 1993; and receiving the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America's highest civilian honor, from President Obama in 2011.

These accomplishments are part of the public record, of course, and many of them are quite well-known. But people may not be as well acquainted with the experiences of Angelou's personal life. Described as "a number of personal misfortunes that might have crushed a lesser will and stilled a less hardy pen" by the New Yorker's Hilton Als, these experiences equipped Angelou with the words and messages that resonate with so many people today — and which can teach the next generation a thing or two about what it means to be a feminist.

Today's feminist community is divided on the issue of sex work, with some hardliners arguing that prostitution is inherently degrading, a lowly profession and not one in which any rational woman would engage. Angelou's experiences make a strong case against that worldview though. Her story goes to show that sex workers come from all sorts of backgrounds and hold all sorts of futures; they are not necessarily victims, and they can, through sex work if they so choose, be powerful and independent women.

Raised in Stamps, Ark., by her grandmother following her parents' divorce, and then by her mother Vivian Johnson in St. Louis, Miss., Angelou's childhood was punctuated by traumatic events, notes the New Yorker. As a young girl, she was raped and threatened into silence by her mother's lover. Following the discovery of the assault, her abuser was found kicked to death, after which Angelou barely spoke for years, fearing her own voice was poison.

Her second memoir, Gather Together in My Name, opens when Angelou is 17 years old and living as a single mother in California. The book follows her journey through the course of two years, during which Angelou pimps for a lesbian couple (an idea she proposed to them), works as a prostitute, almost loses her son to a kidnapping caretaker and only avoids drug addiction due to a chance encounter with a friendly junkie who warns her of heroine's side effects. Despite these difficult experiences — what Angelou called "life's assaults" — the memoirist ended the book on a more hopeful note, saying "I had no idea what I was going to make of my life, but I had given a promise and found my innocence. I swore I'd never lose it again."

As Angelou wrote in one of her most famous poems, "You may trod me in the very dirt / But still, like dust, I'll rise."

Image Credit: Getty

Angelou had a long and illustrious professional life, from San Francisco's first black female streetcar conductor to magazine editor in Cairo to Tony-nominated Broadway actress. But her experiences in the sex work industry — on both the pimping and the prostitution side — were arguably among the more formative in her path to published poet, successful memoirist and influential feminist.

Those encounters may not always have been particularly pleasant. On her experiences as a sex worker, Angelou wrote in Gather Together in My Name:

I sat thinking about the spent day. The faces, bodies and smells of the tricks made an unending paisley pattern in my mind. Except for the Tamiroffish first customer, the others had no individual characteristics. The strong Lysol washing water stung my eyes and a film of vapor coated my adenoids. I had expected the loud screams of total orgasmic release and felt terribly inadequate when the men had finished with grunts and yanked up their pants without thanks.

Angelou called Gather Together in My Name the "most painful book I've ever written." But she did not feel shame at her past, nor make any attempt to cover up that part of her autobiography. Although Angelou said in an interview with In Context magazine that "[she] wouldn't suggest it for anybody," she agreed her experiences with the sex work industry eventually led to her leading an enriched, fulfilled life.

Angelou's words give her readers courage and hope. She shared her experiences because "too many people tell young folks, 'I never did anything wrong ... I have no skeletons in my closet.'" Young people then see themselves as bad people, and "they can't forgive themselves and go on with their lives." But Angelou's story, if nothing else, speaks to the great heights that can be reached from even the darkest of places.

That's really what Maya Angelou was all about — not just the black experience, not just the female experience, but the humanity behind it all. "I speak to the black experience," she said, "but I am always talking about the human condition — about what we can endure, dream, fail at and survive."

When feminism fixates on what other women should and should not be doing — from sex work to marriage, career paths and lifestyle choices — it loses its core mission of equality, diversity and acceptance. It fails its women, and it fails its leaders, such as Maya Angelou. As Angelou said, "The sadness of the women's movement is that they don't allow the necessity of love ... I don't personally trust any revolution where love is not allowed.”