Harvard Astronomers Just Discovered the 'Godzilla of Earths'

The news: The Earth is only a tiny speck in the universe, and it takes discoveries like this to put our miniscule size in perspective.

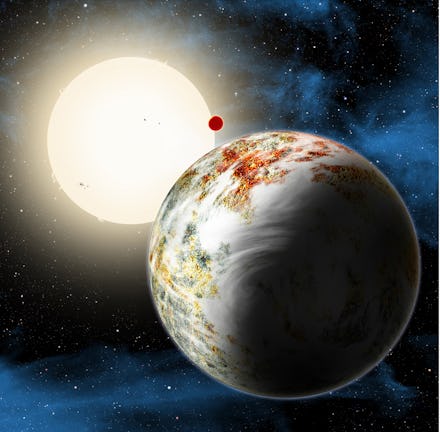

On Monday, astronomers from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics announced their discovery of a so-called "mega-Earth": a planet called Kepler-10c that is about twice the size of and 17 times heavier than our own. And by all accounts, it shouldn't exist.

"This is the Godzilla of Earths!" Harvard astronomer Dimitar Sasselov said in a statement. "But unlike the movie monster, Kepler-10c has positive implications for life."

Image Credit: Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics

An anomaly: Scientists have known about Kepler-10c for years, but most assumed that it was a "mini-Neptune" — a planet with a thick, gaseous atmosphere. But new measurements of the planet's massive weight reveal what must be a dense composition of rocks, solids and trapped water.

However, this composition completely contradicts established planet formation theory: When a planet composed mostly of rock and iron reaches around 10 times the mass of Earth, its powerful gravity starts vacuuming surrounding gases, and most of its mass is eventually comprised of hydrogen, helium, hydrogen dioxide and other gases. For some reason, this didn't happen with Kepler 10c. "Our first thought was that we couldn't really believe it," said astronomer Xavier Dumusque, who made the discovery.

"Understanding the transition from rocky planets to planets defined by a hydrogen-dominated envelope [gas giants] is critical to planet formation theory. Kepler-10c stands out … in direct challenge to theory," the research team announced in a paper.

This is an important find in the search for a "mirror Earth": Scientists have complied a list of prequisites for a planet to sustain life: It needs to have a mass similar to Earth's and must maintain a similar distance from its own sun. Much larger planets, like Kepler-10c, were considered too gaseous and not rocky enough to sustain life.

Image Credit: NASA

Kepler-10c is also ridiculously old. At 11 billion years old, it's only three billion years younger than the Big Bang. It was also formed when silicon and iron were deficient, and lacks sufficient rocks. "Finding Kepler-10c tells us that rocky planets could form much earlier than we thought. And if you can make rocks, you can make life," added Sasselov.

Those prerequisites have seriously narrowed the field, but the discovery of Kepler-10c's composition has blasted them wide open. Many of the findings necessitate a second look at alien planets previously ruled out within the search for Earth-like planets to study. After all, astronomers don't even understand how Kepler-10c is real: "We really don't have any good ideas," Sasselov told TIME.

But that doesn't mean it's a good idea to move to Kepler-10c either. Its conditions are rather unsuitable for human life. At a temperature of 485°K (211°C/413°F), it's four times hotter than Jupiter, it's far too close to its star to retain water, it has 45-day years and it exhibits a surface gravity of about 30 m/s², three times that of Earth's.