Dear Food Industry: You Owe Your Success to Science

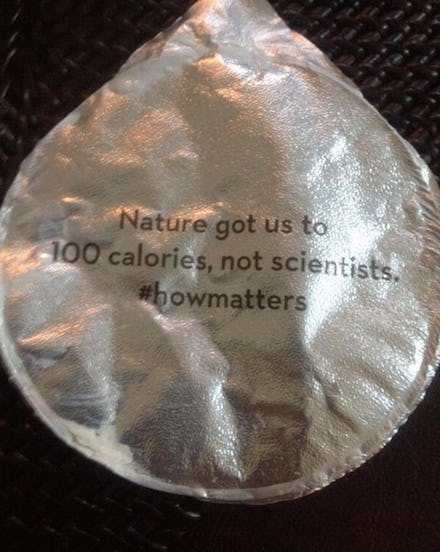

This is a Chobani yogurt lid.

The flimsy piece of aluminum ignited a recent Twitter war after some scientists and science writers took issue with the yogurt company's bold insinuations.

Chobani's advertising team seems to have forgotten that most of the ingredients that go into its yogurt are the product of years of scientific research. So John Coupland of Popular Science reminded them. Let's not forget that nonfat pasteurized milk, the yogurt's main ingredient, wouldn't be safe to consume if microbiologist Louis Pasteur had not popularized the technique of heating milk to prevent tiny bacteria from collecting inside.

Other companies, too, have recently taken up the science versus nature campaign, and it's not going too well for them either.

For all of those at Finagle a Bagel who've latched onto the "Bakers, Not Scientists" slogan, bakers actually are chemists. Anyone who has made a batch of chocolate chip cookies knows that the process of baking relies on precise measurements — not only of ingredients but also of heat — which guide the chemical reactions that turn flour and butter into a gooey treat.

Here are some of the main ingredients (and the chemistry behind them) in a batch of cookies:

Flour: Gives the cookies their bulk.

Yeast (usually used to make bread, not cookies, but can be used to give them added fluffiness): Tiny organisms that feed on starch and sugars, releasing carbon dioxide, alcohol and sugar in the process. The carbon dioxide creates bubbles that give the dough its light, airy texture.

Butter: Forms an emulsion with the other ingredients in the dough, making the cookies chewy and soft. It also helps prevent the carbon dioxide bubbles from escaping from the mixture too soon, which could leave the cookies flat.

Baking powder: When dissolved in water and heated, it releases carbon dioxide. The chemical reaction would look like this:

NaHCO3 + H+ → Na+ + H2O + CO2

Sugar: Feeds the yeast and undergoes a series of chemical reactions above 320 degrees Fahrenheit that form the brown crust of many baked goods.

Next time you take a bite of, well, pretty much anything, thank a scientist.