Why Tens of Thousands of Rape Kits Were Never Tested in the U.S. — Until Now

There are two reasons: Money and policy.

While no official count exists, more than 100,000 rape kits (some experts estimate up to 400,000) sit untested in crime labs across the nation. Congress was expected to approve an allocation of $41 million to examine DNA samples that remain untested after rape crimes on June 18. The grant is part of a large spending bill that will fund the 2015 budget, but for the second time in a week, the preliminary vote was cancelled on Wednesday.

Thousands of sexual assault victims are being denied a very basic right: To be able to prosecute their assailant. Many victims don't know that their rape-kits remain untested, which frequently means that violent offenders roam free on our streets. The persistent problem of backlogs in the United States is even bringing together both political parties.

President Obama requested $35 million in testing funds from the Department of Justice in March as part of his 2015 budget. And the House of Representatives approved a bill to grant the aforementioned $41 million to the efforts of testing sexual assault kit backlogs in May. If Congress approves this grant, there would be a sum of $117 million dedicated to clearing out backlogs.

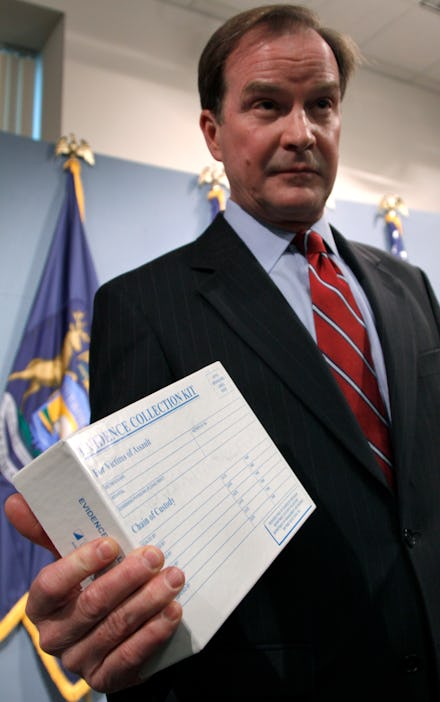

Money problems: After a sexual assault, hospitals gather evidence from the victim's person that may provide essential DNA evidence of who the perpetrator of the assault is and what crime exactly was committed. In order to obtain that evidence, crime labs must test the so called rape-kit for DNA samples.

Testing a single rape-kit can cost between $500 and $1,500. And the $117 million would lessen backlogs in places like Detroit, which has 11,000 untested kits. Since 2004, the Justice Department has appropriated more than $1.2 billion to expand crime lab DNA testing.

It's worth the cost. Testing backlogs is an effective way to prosecute sexual assault offenders. When Detroit began examining just 10% of the backlog, law enforcement found matches for 46 serial rapists. Similarly, after New York City processed its backlog of 17,000 kits, arrest rates in rape cases rose from 40% to 70%.

But as backlogs continue to grow, DNA collection occurs much more rapidly than what lab capacity allows for. This means there is not enough money to process the number of cases that end up in crime labs.

Additionally, there's the complications surrounding money management. A large portion of the funding is said to have been used for lab costs to clear up rape-kit backlogs, but some labs had the option of spending the money in alternative ways.

Which brings us to the policy side of rape-kit testing. Because of unspecified policy guidelines, the allocated money can be used to train crime lab auditors, to reduce crime lab backlog other than rape-kit testing or to help increase the lab capacity.

This was at the center of Sen. Tom Coburn's (R-Okla.) criticism of the Violence Against Women Act in 2013. He cited that the Department of Justice spent $4 billion annually on various grant programs that are both ineffective and overlap.

Part of that overlap may have come from the Debbie Smith DNA Backlog Grant Program. The program began in 2004 and targeted backlogs of DNA testing in crime labs. But the funds from the Debbie Smith grant have been used in part for other purposes.

That policy dysfunction was proven by the Government Accountability Office, the section of Congress that conducts audits. They stated that from 2008 to 2012 Congress allocated $691 million to the Debbie Smith program. During the audit, they found that the Justice Department was not monitoring the grants doled out to them. The Justice Department had spent more than one-third of that budget on "initiatives not directly benefiting state and local DNA backlog efforts," mainly because the money was given without specification about how it would be spent and without any sort of guidelines to measure if the backlogs were reduced through those funds.

As a bipartisan issue, Congress is expected to support the $41 million allocation. The hope is that with a larger budget, the government will be able alleviate state backlogs as well as establish new rape-kit policies and guidelines, so that the rape victims who need due process will be able to have their days in court.