A writer’s trans daughter made him see all the damaging concepts the classic 1985 sci-fi flick pushed.

Rethinking “Back to the Future”

Hits Different is a new series that takes a second look at a TV show, song, album, episode, movie, scene, or clip from the past that, in our current context, just hits different. What was the world like when you first considered this piece of culture, and what’s changed? Does it hold up as timeless, or is it better left to the past? Pitch us at features@mic.com.

David Gerrold’s The Man Who Folded Himself is a queer time-travel novel about how bending time out of its straight line makes it possible to be queer. The protagonist, Daniel Eakins, is given a Timebelt by his Uncle Jim. He proceeds to use it to create virtually infinite alternate timelines, in which he meets many versions of himself, and often even has sex with them. His own past history morphs and changes and disappears; he remakes himself and even gives birth to himself, creating his own community and his own story. “I have spent a lifetime analyzing my life. Living it. And rewriting it to suit me,” he says at the conclusion, in bittersweet triumph.

The Man Who Folded Himself was originally published in 1976. But I didn’t read it until last year, in an updated 2003 edition that adds mentions of 9/11. So it wasn’t a frame of reference for me when I first saw Back to the Future in theaters in 1985. For that matter, living in a very homophobic, mostly Catholic community in northeastern Pennsylvania, I barely knew queer people existed. I think I’d met one out gay couple in my life.

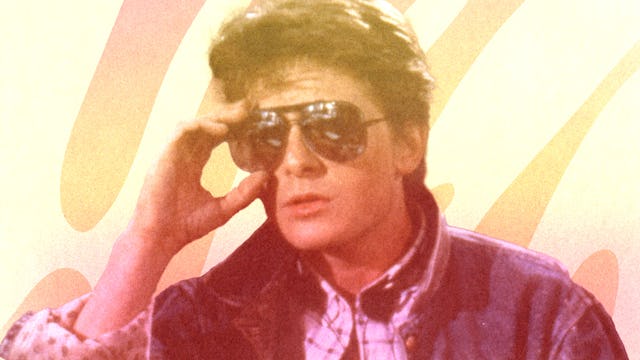

Queerness certainly didn’t seem to have anything to do with the story of Marty McFly (Michael J. Fox), a resolutely hetero Hollywood cool kid who spends his whole time in the past trying to restore the life he had in the present. Marty just wants to make sure his parents get together so he can return to his own time and go on a date with his blandly supportive girlfriend Jennifer (Claudia Wells.)

Time being what it is, I don’t exactly remember what I thought of Back to the Future 37 years ago. It had stunts and jokes and a fun performance by Christopher Lloyd as Doc Brown, the inventor of the nuclear-powered time-traveling DeLorean. I can’t go back and ask myself. But I presume I liked it well enough.

Now, though, I have my own trans daughter around Marty’s age, who absolutely loathes Back to the Future. When I brought it up, she rolled her eyes. “It’s evil,” she said. “It’s a cishet fantasy of repression.” Then she went back to texting her other queer friends. Or, possibly, to writing her own time travel novel. Which adamantly is not about straightening out the path of heterosexual love.

“Evil” is a strong word. But it’s not difficult to see why a trans kid might find Back to the Future alienating. In-narrative, Marty ends up in the past by accident thanks to a surprise attack by angry Libyan terrorists from whom the Doc stole plutonium (the film’s racial politics are a whole other essay.)

Thematically, though, Marty needs to go back in time from 1985 to 1955 in order to fix his family. His mother and his father do not conform to standard heterosexual gender norms; their marriage is out of sync. Marty must get them on the right path before going on his own first date with Jennifer.

The signs of gendered chaos are in the present; Marty’s dad George (Crispin Glover) is a rail-thin, greasy-haired lickspittle, who laughs like a cowed hyena while shuffling and kowtowing to his bullying boss, Biff. Glover plays the character right on the edge of caricature, where nerd stereotypes and queer stereotypes merge into a jittery, flamboyant portrait of stuttering unmanliness. Lea Thompson as wife Lorraine is for her part alcoholic, overweight, puritanical, and overbearing — failing to fulfill the dual Hollywood feminine roles of decorative helpmeet and maternal caregiver.

Marty’s parents are failing at gender. That’s because they’ve failed at narrative: George and Lorraine don’t have the right heterosexual backstory. They met, we learn, when Lorraine’s father hit George with his car. Lorraine, succumbing to “Florence Nightingale syndrome,” pitied him and fell in love with his weakness, rather than his strength. She tells her kids, “If Grandpa hadn’t hit him with the car, you never would have been born.” Reproduction is the result not of good, healthy heterosexuality, but of a male/male encounter, in which George is (literally) on the bottom, under the car.

When Marty goes back into the past, one of the first things he does is push George out of the way of that automobile. This threatens to erase his own existence, since his parents now never fell in love and he was never born. He has to try to get them back together — a task complicated by the fact that the car hit him instead, and Lorraine now has a crush on her own (future) son.

Marty is trapped in a kind of Oedipal fugue. Psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud says that boys should overcome their love for their mother and their jealousy of their father in order to form heterosexual relationships. Instead, Marty falls backward into an incestuous potential with Lorraine — and with his father too.

During his initial meeting with his dad in the past in a diner, Marty stares at George with disturbing intensity. He’s supposed to be shocked to see his father as a young man. But when I watch the scene now, it looks a lot like Marty is scoping George out, and that George is nervous about being cruised. The disordered developmental timeline creates (as per Freud) queer, deviant, and dangerous possibilities, which Marty must rectify if he doesn’t want to lose his (hetero, normal, Hollywood hero) self.

Marty sets about fixing his parents up by trying to teach George how to be a good heterosexual man. A la Cyrano, albeit with less success, he tells George what to say to Lorraine (“You are my density!”). More aggressively, he organizes a scenario in which George can take the role of conquering hero. Marty is taking Lorraine to the school dance and plans to start molesting her in the car. The plan is for George to walk up on schedule, fling the door wide, declare “Get your damn hands off her!” and Lorraine will fall for him.

In the event, Biff shows up and is actually assaulting Lorraine when George throws the door open. George manages to rescue the girl in true Hollywood fashion, and they kiss at the dance, restoring Marty to his rightful place in the timeline — except better.

Because George courted Lorraine in the narratively correct, manly way, their lives are now filled with hetero happiness. To Marty’s amazement when he returns to the present he discovers his mother is fit, pretty, and has a healthy attitude towards sex. His dad is a successful science-fiction writer, who encourages his kids to pursue their dreams and plays a mean game of tennis. Biff works for George, rather than the other way around.

Glover reportedly protested at the film’s equation of happiness with wealth. That equation isn’t incidental though. Queer theorist Jack Halberstam explained in 2005 that “a middle-class logic” of heterosexual reproduction upholds “respectability, and notions of the normal.” In other words, the “right” narrative of love, sex, and child-rearing is supposed to produce both heterosexuality and affluence. Time is progress, which is success. And success is a happy narrative of male strength, female admiration, and the fertile love that results. “It’s a movie that reinforces all the status quos,” as my daughter told me.

Meanwhile, back in the present, that daughter is busy showing me every day that past and future aren’t a linear story of teleological reproduction of gender. Queer stories are often stories of disruption, reevaluation, detours, and zig-zags. You think you’re one person, on that one Hollywood path to a gendered self, and then suddenly not just your present changes, but your future and past. Oh, you say, that’s why she got mad when a male friend told her Frozen should have a guy as the lead. Oh, that’s why all her friends were girls. That’s why, in part, my daughter is so amazing — because she doesn’t fit in anyone else’s story.

Back to the Future tells you that if you had a time machine, you could fit everyone to the one story. You could fix all the genders and erase all the queerness. But that was never true, as David Gerrold could have told me. If I see Back to the Future differently now, it’s not because time has passed it by. It’s because there was always more to time, and to love, than linear-minded Marty was willing to look for on that DeLorean straightaway.