Bill Russell is the true GOAT — on and off the court

Along with a legendary career that included 11 NBA championships, he brought an equal passion to fighting for human rights — even at risk of his own safety.

The very first basketball game I watched featured Bill Russell. It was in March 1968, and Russell’s Celtics were facing Oscar Robertson’s Cincinnati Royals (now the Sacramento Kings) in a nationally televised match. I was new to basketball, but I wasn’t new to my Dad’s insistence that I see as many legendary athletes as possible. He probably already knew that his eight-year-old chess-obsessed, cello-playing son wasn’t going to emulate the magnificent athleticism of Willie Mays or Gale Sayers, but he wanted me to appreciate the intelligence and savvy that these men brought to competition. He wanted me to bring the same fire to my homework and school activities.

Robertson was spectacular, but Russell didn’t impress me as much; he wasn’t scoring like Big O was, and I voiced my disappointment. I remember my Dad’s exasperated frown. Then he chuckled as he often did when he thought his companion wasn’t thinking deeply enough (growing up, I heard that chuckle a lot). “This isn’t tennis,” he said. “To appreciate Russell, you have to watch the whole court.”

That was an understatement, and as I grew to become a hoops-obsessed teenager and adult, I got it. Russell’s impact was to prevent his five opponents from getting the shots they wanted. And should they dare to challenge him, he wouldn’t knock their shots into the stands; he’d intentionally deflect them, so that he could grab the ball and start a fastbreak for the Celtics. During Russell’s tenure, Boston was the top-rated defense in 12 of his 13 seasons. He didn’t coin the adage “defense wins championships,” but his Celtics were Exhibit A in support of it. With Russell on the floor and then as a player-coach (the first Black coach in league history), Boston won 11 titles in 13 seasons. Russell passed away on July 31, 2022 at the age of 88, and his accomplishments deserve deep appreciation and recognition.

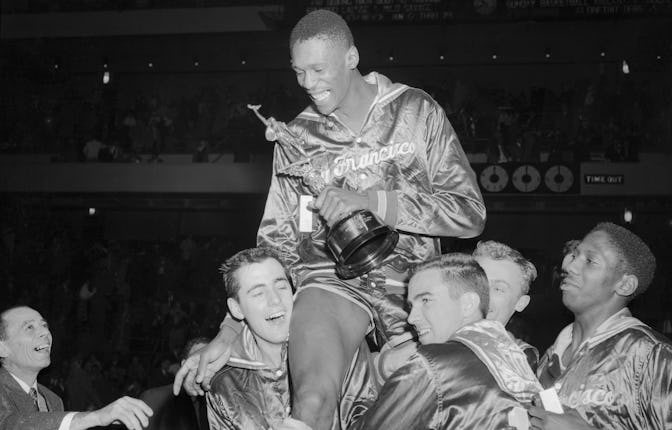

Basketball fans love to debate which player is the GOAT, greatest of all time, and the discussion typically centers on Michael Jordan and his six championship rings or LeBron James and his eight straight Finals appearances. James and Jordan are all-time greats, but Russell’s 11 titles are more than both of them combined. Yes, combined. Each of those players have an equal amount of NBA Finals MVPs to their name — but the award, itself, is named after Russell. In addition, Russell led his University of San Francisco teams to consecutive NCAA titles. Dating back to his college years, Russell’s teams were 21-0 in winner-take-all games. He didn’t coin the term “clutch,” but his career is an excellent definition.

Yet, defining Russell for his remarkable on-court career is as shortsighted as my eight-year-old ass was while watching my first game. He was an unrelenting, outspoken leader on behalf of human rights, and he often paid the price.

William Felton Russell was born in Monroe, Louisiana in 1934. His family struggled with the racism of the Jim Crow era, and joined the Great Migration, relocating to Oakland, California in 1942. His Mom died suddenly when he was 12, and he became a bookworm. He often said his prized possession as a youth was his library card.

When Russell arrived in the NBA in 1956, there were only a handful of African American players, probably the result of informal quota systems that were common throughout professional sports. Russell spoke out against the practice, and by his retirement in 1969, Black players comprised a majority. By then, Russell had appeared with Muhammad Ali at the Cleveland Summit, a June 1967 gathering of leading Black athletes in support of the legendary boxer’s anti-war stand, which led to a ban that cost him his heavyweight title and prime years of his career.

In 1963, following the assassination of Civil Rights leader Medgar Evers in Mississippi, Russell, at the request of Evers’s brother Charles, came South and held an integrated basketball clinic at a playground in Jackson. Members of the Ku Klux Klan watched the clinic from across the street. At night Evers kept a rifle handy as he guarded Russell’s motel room. Russell led boycotts and supported those that he didn’t; his pursuit of justice in America was as zealous as his pursuit of victory on a basketball court.

He faced determined opposition in Boston too. After taking his family on a vacation, he returned to find his home was ransacked, his trophies destroyed, racist epithets scrawled on the walls, and defecation on his bed.

In a 1987 essay for the New York Times, Bill’s daughter Karen Russell recounted, “Every time the Celtics went out on the road, vandals would come and tip over our garbage cans. My father went to the police station to complain. The police told him that raccoons were responsible, so he asked where he could apply for a gun permit. The raccoons never came back.” The FBI kept a file on Russell that called him an “arrogant Negro.”

Contrast that with the right-wing media approbation and social media trolling that James and other outspoken ballers receive today. Russell didn’t crave media attention; he wasn’t out to build his brand.

Looking back, 54 years later, I think my Dad most wanted me to admire Russell for his intellect. My Dad was also from the South and understood that America had limited tolerance for African Americans and even less for intellectuals of color. The next basketball great he turned me onto was a college player, Lew Alcindor — who, as Kareem Abdul Jabbar, had a storied career that belongs in the GOAT conversation, too. He’s the athlete that most closely followed Russell’s path.

In a tweet following Russell’s death, Abdul Jabbar wrote, “Bill Russell was the quintessential big man. Not because of his height but because of the size of his heart.”