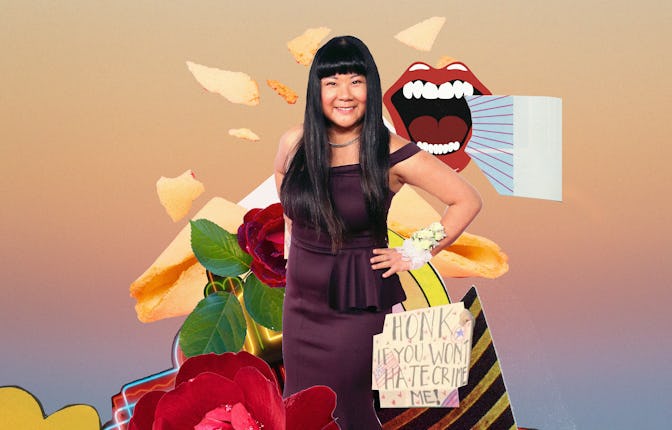

Honk if you won’t hate crime Jenny Yang!

The labor organizer turned standup comedian is here to destroy “fried-rice comedy” once and for all.

The Good Ones is a new series from Mic about celebrities who are living their values through their art. These are the actors, artists, musicians, and creatives who let the world know exactly who they are, and are paving the way for the next generation. Think you know a Good One? Get in touch at features@mic.com.

Last April, the day after then-presidential hopeful Andrew Yang published an op-ed in the Washington Post calling for Asian Americans to “embrace and show our American-ness” to combat a rise in anti-Asian violence, comedian and writer Jenny Yang (no relation, if it needs to be said) took her cell phone to a busy street corner in Los Angeles to film a response.

She was, as she wrote on Twitter at the time, “livid” that Yang’s op-ed promoted the idea that Asian Americans should shoulder the burden to combat racist acts — and that the way to do so was through shallow patriotism. Her initial reaction was man, fuck you, Andrew Yang. But while other prominent Asian American artists and advocates, like actor George Takei, condemned Yang with solemn rebuttals and op-eds, Jenny decided to skewer him with some pointed satire. Armed with a sign that reads HONK IF YOU WON’T HATE CRIME ME, Jenny made a video of herself handing out copies of her “American resume” on the street corner (Skills include “Yelling WOO!” and “Three chords on an acoustic guitar.”) She’s so American, she says at one point, that “I like to ask for ranch dressing wherever I go.”

This video was the sort of biting humor Jenny Yang has become known for. It’s led to her name being included on lists of comedians on the rise alongside Ziwe Fumodoh and Quinta Brunson. In 2016, Yang took aim at a much-derided Bon Appetit video featuring a white chef explaining how to eat pho. (The video has since been removed and replaced with an apology.) Rather than issue yet another limp, cookie-cutter polemic about cultural appropriation, Yang’s video, which features her as a chef who reverently speaks about the proper way to serve a peanut butter and jelly sandwich, was a mirror that reflected back just how eye-rolling white foodie culture can be, meeting it with the exact amount of derision that it warranted. (“PB&J is a complex experience. It’s sweet and savory.”) How else do you combat absurdity except with the absurd?

In the case of Andrew Yang’s op-ed, there was a laughable naivete to what he wrote, a dudebro with entirely too much confidence in his ideas. As Jenny told the Hollywood Reporter, “It’s funny he would mention wearing red white, and blue, or Natalie Chou wearing a UCLA basketball uniform.” (Chou, a member of UCLA’s women's basketball team who had spoken out against anti-Asian violence in March of that year, later shared in an interview that Yang hadn’t quite understood the point she was trying to make when he mentioned her in his op-ed). “Are we just going to walk around wearing UCLA basketball gear every day to make sure we’re not a target of anti-Asian racism?”

When we spoke recently over Zoom, Jenny was more muted in her criticism about Andrew Yang. “I'm sure he’s a fine human being,” she said. But, she added, as “a public persona, he’s just so problematic.” Jenny was talking as she drove the streets of Los Angeles, which has been her home since she and her family immigrated from Taiwan when she was five years old.

In interviews, she regularly quips that no young Asian immigrant girl is ever told they can have a career in comedy. But from a young age, Jenny was drawn to both writing and performing for an audience: she rapped in her English classes and acted out characters for book reports. As the youngest in her family, Jenny was regularly asked by her parents to interpret for them and translate documents; she internalized that words have power, and so does the person who wields them. “It was always a source of processing when I didn't feel like I had peers or family members that could understand me or give me guidance because I was the most acculturated,” Yang said of writing. “It was the one thing in an upbringing of not ever centering your needs as a little immigrant girl.”

In college at Swarthmore around the turn of the millennium, Jenny experienced a political awakening. “I was a born-again activist,” she told me. She learned “that there’s a language, a system of analysis that helps explain the things that I experienced growing up, all the -isms and prejudices” that made her feel unwelcome as a young immigrant, and explained why her mother, a garment worker, was so tired all of the time.

No young Asian immigrant girl is ever told they can have a career in comedy.

As a student, Yang made a name for herself as a performance poet, but she focused her sights on a career in politics and community activism. She worked for a labor union, an SEIU local, shortly after graduation, and while she quickly moved up the ranks and became a director, she became disillusioned with the union’s top leadership. Unions, she found, for all of their necessary work to strengthen workers' rights, can be dismissive of the needs of their own workers.

The movement can eat its own, and it ate up Jenny Yang. “It started to turn into, number one, you're a fucking hot mess. You don't know the actual definition of self-care because you're a fucking workaholic who overidentifies with your job and this labor movement, and therefore, you’re probably working too long hours, drinking too much, sacrificing your prime fuck around and childbearing years.”

She had the bread, but she wanted the roses, too. She had begun doing standup before she quit her union job, which “gave me some of my sanity back.” Comedy became her form of self-care, a sort of recovery room where she was allowed to bring her whole self, so she took the leap. “I accepted that I was willing to give up everything I had and go back home to live with my parents in order to make this happen, and only eat rice and beans,” Jenny said. “I remember thinking, ‘I have nothing to lose in order to not feel like I am desperate for something.’”

It was the mid-2000s, and she found a comedy scene dominated by “boring” white male twenty-somethings. The few shows devoted to Asian American comics weren’t much better, often pandering to antiquated, tired stereotypes that she summed up as “fried rice comedy” — more laughing at than laughing with. She honed her brand of physical, frenetic stand-up at open mics and bringer shows. If you’ve seen Yang perform, then you’re familiar with how she deploys her face, scrunched up like what I can only describe as a clenched butthole, to perfect effect. She’d grit her teeth listening to jokes about dating Asian girls and how their vaginas were like fortune cookies. Jenny realized she wanted to carve out a space for her and other Asian Americans to perform “our full diversity and dopeness.”

In 2012, Yang set out to make, as she put it, “a different type of Asian American-focused show.” Disoriented Comedy, the name she and her two collaborators Yola Lu and Atsuko Okatsuka gave their show, was both a way to signal that it would approach being Asian American from a wry, knowing angle. Disoriented was just the first of many comedy spaces Yang has helped birth. In 2015, she and others launched The Comedy Comedy Festival: A Comedy Festival, whose name was a rejoinder to the universality that is given to white Americans and their experiences but not generally extended to people of color. “The joke was, it doesn't have to be named the Ching Chong Comedy Festival for you to know it's Asian American talent,” she said. “Why do you always need to give yourself this additional modifier?”

“Storytelling is a fundamental part of organizing.”

When we spoke in August, Jenny was looking forward to focusing on her own craft; she was now a writer for the show Last Man Standing and the upcoming Gordita Chronicles, as well as the host of an upcoming podcast. Before the pandemic, she was about to launch her own monthly comedy show on the self-care industrial complex. “I’m very good at talking about race and I'm never going to stop talking about it,” she said. “I'm not even worried about being, quote-unquote, pigeonholed.” Yang, after all, is spinning her lived experience and her framework for understanding the world into comedy. It’s what so many artists do, even if it’s not labeled as identity-based. “But I wanted people to know I was also obsessed about other things,” she said.

Jenny sometimes says she left the labor movement for the comedy world, but she also brought labor politics to the comedy community. Her organizer’s mindset was evident during the height of the pandemic last year. Sad and stuck at home, Yang hit upon the idea of hosting a virtual comedy show using the video game Animal Crossing, which she called Comedy Crossing. Vulture called it the “most joyful live comedy” happening at the time, and Yang used the show to raise more than $30,000 from her audience for mutual aid funds, bail funds, and Black-led organizing efforts.

Yang has often talked about bringing the principle of Organizing 101 to her comedy work — meeting people where they are and encouraging them to do more. At a South By Southwest panel in 2017, referencing her popular riff on that Bon Appetit video, she nudged people who were upset by that video to expand the boundaries of their outrage. “Asians, if we just took our foodie culture energy and just channel that shit into actual town hall meetings and politics, like you don’t understand, we’d be powerful,” she said, calling on people to “translate food porn into political action.”

Yang has spent much of the past decade creating space not just for herself but others in the comedy world, and she is keenly aware that this work has come at some cost. “I often wonder how much further along in my career I would be if I could just focus on the funny. I’ve become a professional diversity producer,” she wrote in Elle in 2018. “What if I could just be a comedian?” For a five-year period, Yang had produced several comedy tours in both L.A. and in cities around the country on top of working on her craft. “I didn't feel like I was able to focus enough on my own writing as much, because so much of the energy was siphoned off to producing and traveling,” she said.

But she will always be an organizer at heart. “Storytelling is a fundamental part of organizing—how you quickly tell people who you are and connect with them and create a shared story,” Yang said. She added, “I come from a labor union perspective. In my head, I was organizing people.”