More than two decades after Tupac Shakur and Tim Roth depicted heroin abusers seeking help to quit, America is still fumbling its drug problem.

25 years later, 'Gridlock’d' reminds us that America never won its war on drugs

Hits Different is a new series that takes a second look at a TV show, song, album, episode, movie, scene, or clip from the past that, in our current context, just hits different. What was the world like when you first considered this piece of culture, and what’s changed? Does it hold up as timeless, or is it better left to the past? Pitch us at features@mic.com.

America would like you to believe that it won the “War On Drugs” that began in the ‘80s. Although unethical politics were the root of the country’s narcotics epidemic, poor people of color were the main recipients of blame and subsequent punishment. Rockefeller Laws handed large swaths of minorities unjust prison sentences for sales and distribution, even just for weed infractions.

The flip side saw people with substance abuse disorders – the sick – also treated and prosecuted like criminals. Pregnant women who tested positive for drugs were preyed upon at their most vulnerable point, by physicians and federal prosecutors alike. Even in creative spaces where art imitated life, the victims and this country’s inept rehabilitation systems were given little spotlight. All of this makes the 1997 film Gridlock’d such a worthy revisit 25 years later.

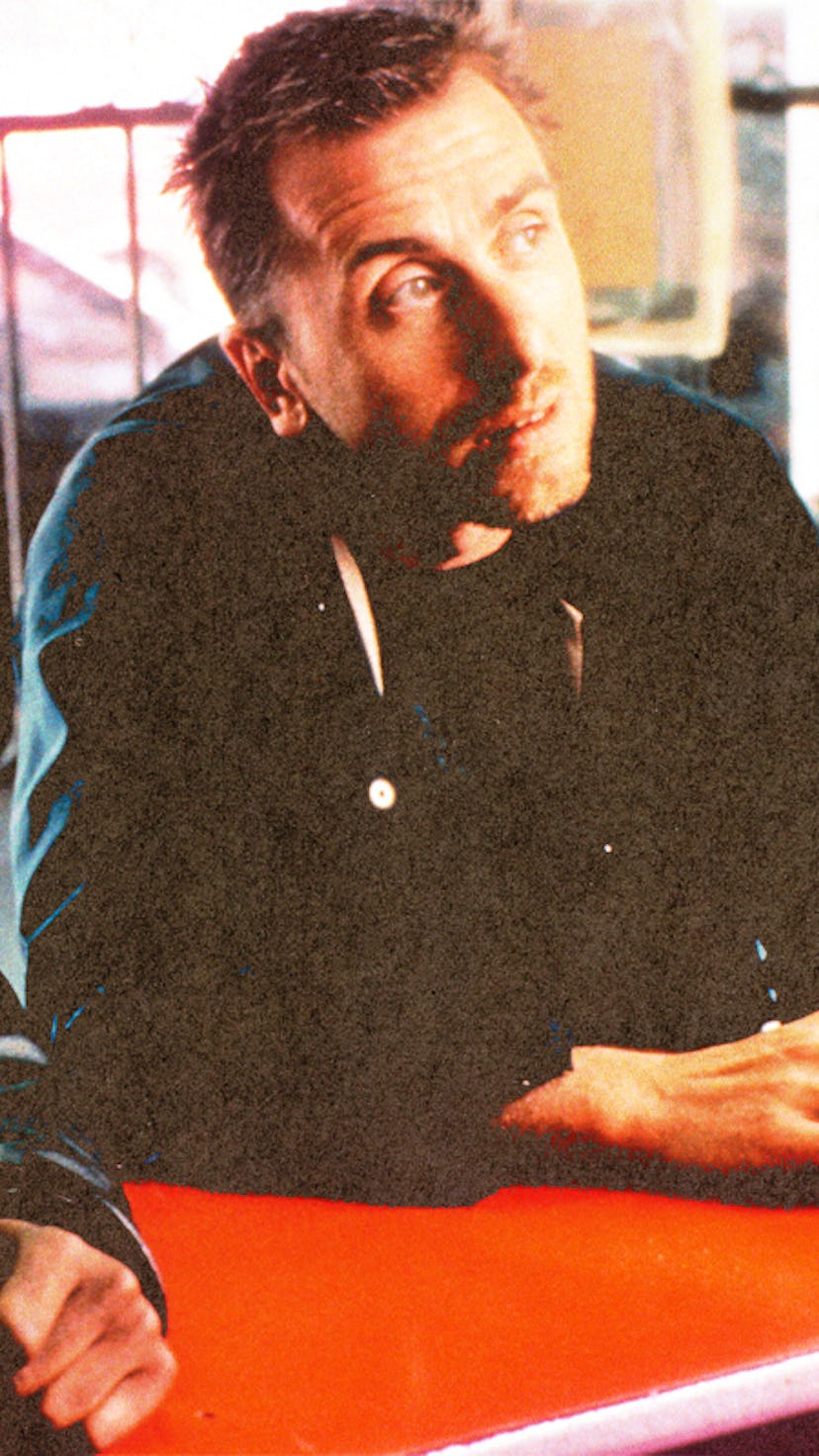

Directed by Vondie Curtis-Hall, known most for his acting in films like Coming To America, Die Hard 2, and the more recent Harriett, Gridlock’d is an indictment on the country’s impotent treatment system. Starring Tupac Shakur and Tim Roth with an ensemble cast including Thandiwe Newton, Lucy Liu, and Bokeem Woodbine, the film is a sort of Dog Day Afternoon dark adventure. Lead characters Spoon (Shakur) and Stretch (Roth) spend a day trying to escape both their habit and a local drug dealer while being given the run-around by various social service employees. The men can’t get into a rehab program without a Medicaid card, but can’t secure a card without a welfare card. They may be able to cut the weeks-long wait for rehab acceptance if they take an AIDS test. A rewatch illuminates just how little progress America has made with addressing its narcotic-ridden population.

A quarter-century ago, like African-Americans post-Civil War, those addicted to street drugs were perceived by the U.S. as a problem that landed unceremoniously on its front door — instead of as the byproduct of its own evil. Campaigns like “Just Say No” used Uncle Sam’s pointer finger to scold the afflicted, segregating them from civil society before they’re tar and feathered.

The crack cocaine era was pinned to Black and brown people, thus handled like a crime issue instead of a health crisis. Today’s “war on drugs” is vastly different in both the drugs we condemn and the way we treat the afflicted – especially since they now largely include White Americans. Because of this, today’s substance abusers are more often treated with compassion and, most importantly, medical attention instead of treated with draconian-like “justice” and thrown behind bars.

In the early 80s and 90s, films like Scarface and New Jack City were lauded for serving audiences cocaine- and crack-affiliated central characters who appeared bigger than life. Heroin, on the other hand, was a taboo topic in Hollywood. Before the 1995 film Kids matured into a cult classic, it was met with some weighty criticism for its portrayal of teenagers who used narcotics with regularity — it even received an adults-only NC-17 rating, one step up from R.

This very climate contributed to Gridlock’d nearly being shelved. A year prior to its release, the distributor Polygram released the film Trainspotting. The studio heads were less than enthusiastic about producing another film about dope-addicted people. When Interscope Records decided to fund the $5 million film, Polygram had a swift change of heart. The power play allowed for Pac’s label Death Row Records — a subsidiary of Interscope — to produce the soundtrack, which was certified Gold by the Recording Industry Association of America, performing better than the movie.

It was crucial to Curtis-Hall that Gridlock’d’s premise would be autobiographical. As a teen, he was a band singer, guitarist, and heavy narcotics user. At age 16, he decided to kick the nasty habit. When it was time for him to pen his first script, he recalled wandering around Detroit (where the film was also set) with a buddy attempting to enter rehab programs without giving out his parent’s address. The last thing he wanted was to make his folks aware of his addiction.

While Hall’s obstacle was understandable considering he was a minor, adults who struggle with narcotic abuse have continuously faced bureaucratic hurdles on their roads to recovery. For a litany of reasons, that path is even more challenging for minority men and women. Access to proper healthcare has been a historic rarity in brown and Black communities. Treatment is either nonexistent in urban cities or riddled with insufficiencies from the staff to medicine.

Gridlock’d’s lead characters being Black and white showed that, while this country’s healthcare system weighs heaviest on the darkest and poorest, it has failed all races. That’s evident from the millions of opioid-related deaths, many of them from an addiction Big Pharma fueled. This stat only increased during the pandemic.

Spoon and Stretch constantly crashed into walls of misinformation because the social service offices were not in cooperation with the recovery programs. There has long been an absence of collaboration within these systems, which often equates to a lack of resources for those who need it most. For both the characters in the movies and people struggling with drugs today, there's a blatant lack of a comprehensive treatment plan — one addressing both physical and mental health — and it shows.

So not only did we lose a war on drugs, but we're living under the false pretense that Spoon and Stretch would have fared totally differently today. Maybe a sequel would pull the wool off of everyone's eyes.