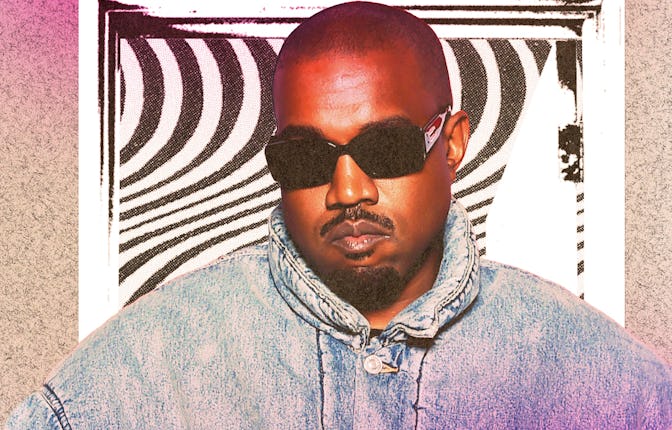

On 'Donda 2,' Kanye West is a ghost within his own music

At its best, the album has some of his most compelling work in nearly a decade. But it’s dreadfully unfinished.

At its best, Donda 2 is eerily wrenching; its early suite of songs about divorce and coming unmoored from family life are among the most compelling things Kanye West has recorded in the past eight years. See “True Love,” the opener where West raps around a hook from the late XXXTentacion: He imagines his kids burrowing beneath Calabasas from his ex-wife’s home to his, only to pick them up for his above-ground visitation and “feel like they’re borrowed.” The open space on the back half of that song, presumably reserved for a second verse that was never written, communicates more weariness than any new vocal could; in the lone, ten-bar verse from the following song, West wonders “What if the surgeon really the serpent?,” which is either a rote joke about the vanity of botox or a rebuke of the doctor who oversaw his mother’s botched, fatal cosmetic surgery 15 years ago.

This is followed by the acapella “Get Lost,” where West’s heavily processed vocals finish on an unresolved and unresolvable “Do I still cross your mind?/If not, then never mind/If not, then never mind,” and “Too Easy,” whose hook pleads, over and over: “I need you to love me.” The album mostly disintegrates from here, seldom communicating the same despair or desperation. Its half-done form also loses most of its potency. The lone exception in the latter regard is the second XXXTentacion collaboration, “Selfish,” a song where West snaps “Don’t look at me like I need medicine” before once again ending the track after a single verse. Here, the brevity helps West — one of the most overexposed men in the world, someone who has at least intermittently marketed every last shred of his private life — pull an incredible trick, making the listener feel like a voyeur who has pried open a hard drive to stare into an abyss.

Of course, this is not a surreptitious peek into the rapper’s vaults. It’s the final-to-this-point draft of a record he’s packaging inside a $200 piece of consumer hardware. If this can be read as the latest fit of marketing hubris in a long series of them, it can also be understood as West’s final, full retreat from radio and the pop charts, which began after the commercial high watermark that was 2007’s Graduation. But it is ultimately a gambit of frustrating cynicism and too little forethought by an artist who has burned much of his goodwill through increasingly crass, diminishing-returns versions of arguments he made with some authority a decade ago.

While some would point to the famously last-minute vocal sessions for 2013’s Yeezus or the rolling re-release and re-edits of 2016’s The Life of Pablo as the beginning of a new approach to finished (or “finished”) work, West’s creative process has been traceable by the public since much earlier in his career. If there was nothing particularly novel about enlisting Timbaland to fashion new drums onto “Stronger” between its white-label release and Graduation proper’s, there certainly was during the rollout of the following year’s 808s & Heartbreak. West broke that album’s lead single, “Love Lockdown,” into stems, which he posted on his website and encouraged fans to remix. Then came a series of possibly authorized, possibly unplanned leaks of nearly-finished 808s songs; to this day I am surprised to hear the new instrumentation on the official versions of tracks like “Robocop” and “Welcome to Heartbreak.”

Forgotten amidst the (now nearly parodic) critical adoration of 2010’s My Beautiful Dark Twisted Fantasy is the fact that, when that album’s tracklist was posted online ahead of its release, many of West’s fans were confused and annoyed. Well over half the tracks had existed online for months in some form or another. But their final versions were longer, more refined, and more baroque; see the electric guitar breakdown that mirrors the vocal sample in the middle of “Devil in a New Dress” orthe extended outro on “Runaway.” West would later say that the sheer man-hours he spent on these records were necessary to fully realize them. “‘On Sight’ ain’t the best version of itself,” he told the hosts of the Breakfast Club in 2013, referring to the opening song from that year’s Yeezus. “But it was under a timeline. [Dark Fantasy’s] ‘All of the Lights’ took two years. ‘On Sight’ took four months. If ‘On Sight’ took two years, and I listened to it more, you’d have more... [“All of the Lights”] started as a Jeezy record with horns on it. Then we put in another bridge, and then Dream wrote the hook, and then Rihanna sang it, and by the time yall got it, it was to the level of the Nike Flyknits or something like that. Yeezus is literally a listening session for the world.”

But whatever scheduling urgency abbreviated the Yeezus sessions merely served to accentuate that album’s themes and aesthetic motifs. Though divisive at the time, West clearly considered that album a success (he should; it’s his best work), and so applied the “listening session for the world” ethos to everything that followed, with frequently disastrous results. And still, with The Life of Pablo, 2018’s ye, and last year’s Donda, an album eventually arrived — days, weeks after West’s self-imposed and -announced deadlines, maybe, but in a form that made “unfinished” a critical judgment rather than simple fact. Donda 2 is the first time he has expected fans to pay for something that is not, in any sense of the word, done.

This rawer presentation has occasionally yielded interesting results, especially when it feels as if the distance between impulse and master recording has been collapsed to nearly nothing. (See the Donda opener “Jail,” which would almost certainly lose its strange nakedness if its vocals were more polished or its arrangement more dynamic.) There are very occasional instances of this on Donda 2: a comic curio about making a gangly SNL cast member’s security detail quit in frustration, a now-excised song where a madcap Future verse (“Blood on my money, see the blood in my eyes”) is juxtaposed with the Talking Heads, the edges of the component parts yet to be sanded down.

But the bulk of Donda 2’s final three-quarters is a mess of finished turns by collaborators and placeholder vocals from West, making for songs that are the worst thing a song can be: dull. This is exacerbated rather than masked by the Stem Player: Isolating elements of a track is only as interesting as the elements themselves, and when there is nothing compelling to rearrange them into, the experience is left to feel naggingly incomplete. It must be said that the player is beautifully designed: sturdy under a soft rubber finish, intuitive even without a display screen. West has compared himself time and time again to Steve Jobs, and the influence of Apple’s hyper-minimal design is clear. Still, it’s difficult to imagine it becoming any sort of coveted consumer item given its lack of significant memory, the ubiquity of DSPs, and the reality that most people have been conditioned to expect their music to live on the same phone they text and email on. A new iPod this is not.

In the same 2013 interview where he explained the difference between “All of the Lights” and “On Sight,” West compared himself to the famous performance artist Marina Abramović. This was in response to Charlamagne Tha God’s insistence that the “Bound 2” video would be better if West himself did not appear in it; West responded that his presence, and the baggage it entails, is necessary for his creative pursuits to make the comment he intends. With Donda 2, it feels for the first time that his presence in the frame’s center has been replaced by a vacuum that can be filled with whatever political or corporate interests West, his fans, his detractors, and his benefactors choose to project into it. Even West’s sloppiest work was once provocative for his very involvement in it. All we’re left with now is middling formal studies by someone who sounds too often as if he couldn’t be bothered to swap out the mannequins for live actors.