Kendrick Sampson is just as skeptical about celebrity activists as you are

The Insecure actor isn't ready to rest.

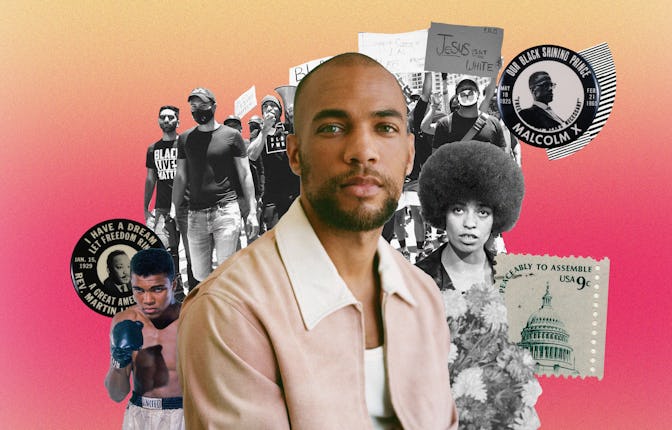

The Good Ones is a new series from Mic about celebrities who are living their values through their art. These are the actors, artists, musicians, and creatives who let the world know exactly who they are, and are paving the way for the next generation. Think you know a Good One? Get in touch at features@mic.com.

Since appearing on ABC’s How to Get Away with Murder, and more recently on HBO’s Insecure, Kendrick Sampson has continuously demonstrated that he sees acting as a vehicle through which he can fight for equity for Black people. Fans of Insecure might know him as Nathan, the charming love interest for the show’s lead character; in recent seasons, his character has been forthcoming about his mental health in a way that expands the Black male experiences we’re used to seeing on television.

Sampson is doing this work off-screen, too. When he’s not on set, he spends much of his time working as an activist in Los Angeles and beyond. Sampson’s desire to make a political statement, both through his onscreen work and as an activist, stems from his childhood. The 33-year-old actor, who is biracial, credits his “militant” Black father with some of his deepest convictions about the ways Black people are portrayed in popular culture. As a young child, he remembers joining his father to watch movies like John Singleton’s 1997 film Rosewood, about a white lynch mob terrorizing a Black community in 1920s Florida, and the 1977 miniseries Roots. “My dad wasn’t [anti-capitalist] like I am,” Sampson tells Mic, “but he grew up during segregation as an orphan. He’s definitely got a fuel.”

Although they might disagree on some ideologies, Sampson has certainly retained his father’s “fuel” and outspokenness. He’s stumped for former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders, advocated for The People’s Budget LA, and sought to enact major cuts to LAPD’s budget and reallocate the funding to social services. In June 2020, he penned a letter signed by more than 300 Black artists and execs asking Hollywood to divest from the police.

The actor has also been vocal about how he’s personally engaged in protest, making headlines last year after he was allegedly hit by rubber bullets seven times while protesting against police brutality in Los Angeles. On December 16, Sampson posted a video to Instagram that showed a police officer in Cartagena, Colombia punching him in the face during an encounter. “This is the 6th time I was stopped in 5 days,” Sampson wrote in the post. “It happens to Black Colombians often.”

When I ask him in August about the progress that’s been made in the year since nationwide protests erupted amid a global pandemic, Sampson pauses and laughs. He says he’s trying to think of how to frame his thoughts in a way that won’t evoke protests from his publicist. Then, he decides to just be frank anyway.

“I don’t know what people expected differently,” he says, addressing reports and data that have shown that police have killed more than 800 people in 2021 and more than 1,000 people since last year’s protests — showing virtually no change in overall deaths per year. “I knew when Joe Biden got in office that people were going to lax, chill out, and be like ‘we got the big baddie out of the office.’” He starts fluttering his hands and singing a song to the tune of “Everybody Rejoice” from The Wiz: “The villain’s gone. Ding dong, the witch is gone. Can you feel a brand new day?’”

He straightens his face. “It’s like, chill out. You just put Joe Biden in there and he’s proven to be exactly who he’s always been in office. If you’re talking about the movement that swept the country, talking about ‘defund the police,’ you think Joe Biden’s going to be an aid to this? You think he’s going to honor that work? It was time to get to work.”

“The fact that police budgets became a popular conversation, when we talk about “defund”...It's the least sexy part of politics. Everybody was talking about it. That's a huge success,” he adds.

Like any celebrity activist, Sampson has been met with his fair share of skepticism. When he appeared in a performance with Lil Baby at the Grammys, reenacting the death of Rayshard Brooks at a Wendy’s in Atlanta during a police interaction, he placed himself at the center of a debate about art and activism. Several fans and writers wondered about the productivity of such performances. At what point does recreating these moments become more harmful and triggering to Black viewers than it is helpful?. The performance, as well as an appearance from activist Tamika Mallory, sparked a fiery debate about performative activism and who it serves. After the event, Samaria Rice, the mother of Tamir Rice, put out an official statement publicly accusing Mallory, Shaun King, Patrisse Cullors, and others of “monopolizing and capitalizing our fight for justice and human rights.”

Sampson understands the tendency to shun celebrity activism. “A lot of it comes off as disingenuous, and to be real, a lot of it is,” he says. “There’s a lack of diligently seeking education and research before we speak, not amplifying the experts and the voices of the people that do the work every day.”

But he’s also been quick to defend other activists and friends from the criticism they’ve received in the past year. “People put all these donations into their organizations and haven’t given them time to build infrastructures. These organizations probably haven’t even found accountants yet to sift through those funds and see what they can actually do to them,” he tells Mic, echoing remarks he recently made to Talib Kweli when asked about criticism aimed at Black Lives Matter co-founder Cullors. “Some people can’t even touch the money yet and they’re exhausted. They've been doing this work nonstop for years with no resources. And now y'all expect them to do all the work and be heavy while y’all rest. People who just got into activism are ready to rest. That was a hard summer, right? We’ve been having this same summer for 10 years.”

Sampson understands the tendency to shun celebrity activism. “A lot of it comes off as disingenuous, and to be real, a lot of it is.”

As a child growing up in Houston, Sampson was so enamored with the art of storytelling he’d often fall asleep with a pile of books on his bed. “It wasn’t very pleasant for my mom during the night when it would just be like *thud* *thud* *thud* thud* as you heard all the books drop off my bed,” he says, mimicking the sound of books hitting the floor. “As a kid, it was kind of my escape.”

Sampson says he began entertaining and telling stories, first through impressions of prominent figures ranging from Tina Turner to Bill Clinton. Once he began attending middle school, Sampson had landed his first role in a school production, playing an Australian character in an interview series. By the time he was a pre-teen, he’d found an agent by looking through the newspaper and began taking acting classes. But the limitations of finding work in film and TV while living in Texas quickly became apparent.

“I knew all of these white kids that were going to LA. There’s a big culture of that in Texas. White kids that have parents who could afford to take off three months and go to LA. My momma was like ‘I’m single. I ain’t about to take off my work for you. When you’re 18 you can do whatever you want.’

“Once I finally turned 18, I made my momma eat her words,” Sampson continued with a laugh. “I didn't look back.”

In Hollywood, there are certain roles that have become standard for budding actors to take on early in their career; shows like Law & Order have become a fun place to spot stars before they land their breakout roles. But, even before public criticism targeted glossy police procedurals in the past year, Sampson says he was wary of roles that would negatively depict or stereotype Black people. “I definitely had a lot of fear it would negatively impact my career,” he says, noting that industry insiders would often remind him that he shouldn’t be turning down roles with such a slim resume. “But I was blessed to find people who would advocate for me and encourage me.”

Sampson’s own experiences in Hollywood were a part of what motivated him to launch his own organization, BLD PWR. The two branches of the organization include a non-profit dedicated to removing police from production sets and dismantling the white supremacist, capitalist gaze from Hollywood, as well as a production studio that creates content that aligns with the organization’s (and Sampson’s) values. The actor says he’ll continue to work in front of the camera, too. He’s mum on the particulars but says he’s waiting to hear back about whether he’s been selected to play a certain historical figure in a biopic.

For now, he’s awaiting the arrival of the final season of Insecure with fans. “I definitely didn’t expect a lot of the things that they wrote in this new season. I don’t think it will be what people expect,” he teases.

Reminiscing on filming the final season, Sampson says the show’s impact will extend far beyond its last episode “Everybody has a book out. Everybody is producing something. People that were production assistants are now in the writer’s room. More than anything, the impact that the show has had on people’s lives behind the scenes, in the public, in the zeitgeist...It’s been really incredible to witness and be a part of.”

He may be quiet about the next steps of his acting career, but Sampson is certain he’s benefited from the Issa effect career-wise. And, as he mentions, the legacy of Insecure extends far beyond the on-screen roles its actors have landed since appearing on the show. Through BLD PWR, Sampson hopes to continue to expand the Black experiences we see on television, further solidifying his contribution to the lasting legacy of the Insecure crew.