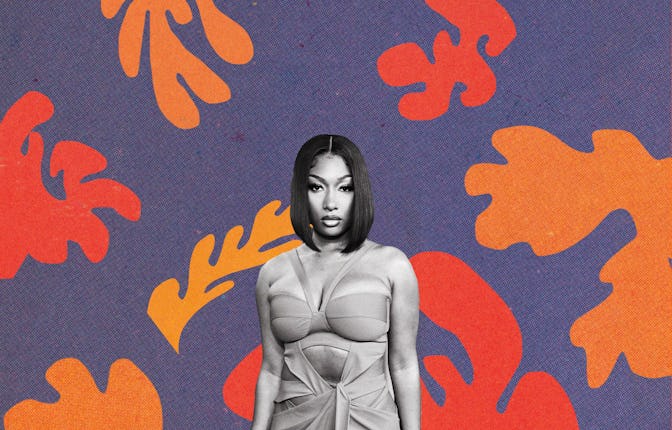

On Traumazine, Megan Thee Stallion shows she’s deeper than “hot girl summer”

The rapper’s sophomore album is a meditation on public and private grief.

Consider Traumazine Megan Thee Stallion’s deconstructed burn book. It’s absent of the cruelty and callousness that’s often fashioned around those created during periods of adolescent uncertainty, uninterested in solely magnifying and mocking the superficial flaws of others. But Traumazine is a public cataloging of the uber-public ways that the Houston rapper’s truth has been turned into farcical amusement. Across 18 tracks, over a dozen of which she underscores her hottie status with reflective and pained revelations, Megan Thee Stallion uses art to cross-examine friends/lovers turned detractors. Each moment of clarity pulses with fury, and after everything has been collated, she holds up the burn book and asks listeners to not only see the horrors she’s lived through, but the ways she’s had to mend and remake her universe. In Meg’s sophomore album, grief is turned into a cleansing ritual; washing off the bullshit, and burning all the fallacies.

On “NDA,” the first track that sees Megan cracking her knuckles before stepping into the spotlight, she takes a metaphorical bat to whatever is in reach and swings her way through insecurity, pettiness, and jealousy, with a line-by-line rundown of her most notable stats. She works harder, seduces easily, and dresses better than anyone who dares to make her feel less than her most polished self. Better yet, her money is both liquid and digital — along with hanging on her neck, wrists, and fingers, it’s also in her mind, and rests in her name. Wealth has kept her company as people fall away, and it’s made escape a temporary but accessible reality. “Goin' through some shit, so I gotta stay busy/Bought a 'Rari, I can't let the shit I'm thinkin' catch up with me,” she raps. In a Spotify interview shortly before the album was released, Megan shared that on her intention on Traumazine was “ inviting the hotties into her head, to show how she’s really been feeling.” She’s been persistently expected to purvey the euphoric “Hot Girl Summer” persona, but now she’s asking fans to grant a little grace, and sit with her as she moves from sun-drenched ecstasy to spending a little time for contemplation and release.

“Not Nice” is one of the most pointed tracks to come from a star who already refuses to beat about the bush. In recent pop culture history, niceness was packaged by Drake via the catchy but toothless “Nice for What,” which stuck the female empowerment landing with as much weight as cotton candy hitting the tarmac. But on this blistering admonition, over a thumping, steady beat reminiscent of 90s musical and lyrical sensibility, Megan rejects the word that’s so easily tossed around to surveil seemingly “unruly” women — “Fuck it bitch, I’m not nice.” She’s accepted that sometimes, when they go low, the proper remedy is to meet them at their level and match their disdain with a lethality that leaves them reeling enough to never try it again. “You got the roaches in your crib sharin' snacks with your kids, Delinquent on your payments, ho, go and post this.” For months, the rapper has shared how she was left isolated and heartbroken while countless voices reshaped truth to suit ulterior motives, and so here she makes the punishment fit the crime, making both public so they can exist alongside each other.

There are several featured artists on Traumazine, and acts like Rico Nasty, Jheke Aiko and Latto’s appearances boost their songs while adding layers to their own artistry. But it’s Megan’s presence that fortifies their cameos with verve and confidence. “Without the money, I don’t budge,” Megan starts off on “Budget,” calling to mind the oft-circulated quote from the supermodel heydays when Evangelista, Campbell, and Crawford would not get out of bed for “less than $10,000 a day.” Latto then goes flow for flow with Megan on the brief interlude, adding mischief and audible eye-rolls: “Latto don't do budgets/Talk shit like Joe Budden/Trips y'all can't pronounce, big jets to Phuket, I'm like, "Fuck it." Sliding over to “Consistency,” Megan is as raunchy as blues legend and godmother of hip-hop Lucille Bogan, whose demands for pleasure and boastful assertions of her insatiable sexual prowess — “I got something between my legs to make a dead man come” — quickened hearts in joints across the country. Aiko, whose feathery tone tends to belie the directness of her lust, lends her voice to express desire for loyalty and good sex in equal amounts. “If you can't give me the time/Then, baby, you can't be mine,” she insists. “….Miss me with the wishy-washy in and out my life.” The track is a siren call and a demand for a grown love that understands honesty and boundaries. On “Scary,” with a standout assist from Rico Nasty, Megan sharpens the foreboding, shadowy gloom of southern gothicism and leans into the region's intimate rituals around horror and rebirth, highlighting those who move in silence and strike with purpose. The song sounds like a chant or even an x-rated story to be shared around a fire when remembering all those who tried to do you harm and failed. As you utter their names, you toss their assigned talismans into the flames, reminding others that like Candyman, your own name is both a curse and an avenging spirit. Megan is putting the naysayers on notice and positioning herself as Houston folklore, something to be respected and also feared.

It’s interesting that her lead singles, “Pressurelicious” featuring Future, and the Dua Lipa-assisted “Sweetest Pie,” are the least compelling moments on this album; when held next to the sexy “Ms Nasty” or the hustling “Gift and a Curse,” they come off as grasps at radio play and streaming numbers. They lack the dimension of “Flip Flop,” a sobering acknowledgment of loss that also outlines the limitations of self-care when you’ve lost people close to you. And they fall short alongside “Her,” which makes a reach for the dancefloor and the charts, riding the waves of dance music currently dominating the soundscape. Soon after the release of her debut album, Good News, culture critic and editor Niela Orr described the work as “a baggy collection of songs that are limited in scope, even though they might have unlimited streaming potential.” Megan’s personal disclosures on the record were tentative and opaque, and the project felt over-stuffed with metaphors and swagger —and whether that was a deflection or act of self-preservation, it kept her from truly addressing how the losses she faced consumed her mind. Two years later, with the amalgamation of her creative eye and her emotional state of mind, she has delivered a record that is not only a showcase of her artistic capabilities, but also a mediation on public and personal grief.

Megan Thee Stallion has been ascending while rebuilding, celebrating while mourning, and creating new safety nets while destroying old habits. In this process of shedding, reality morphs into fiction, and stories become the tools we use to stay hopeful and alive. Traumazine is the active forming of a life, and Megan is making sure we see and hear her fight for new beginnings.