Prince's 'Diamonds and Pearls' laid a daring blueprint for Black musicians

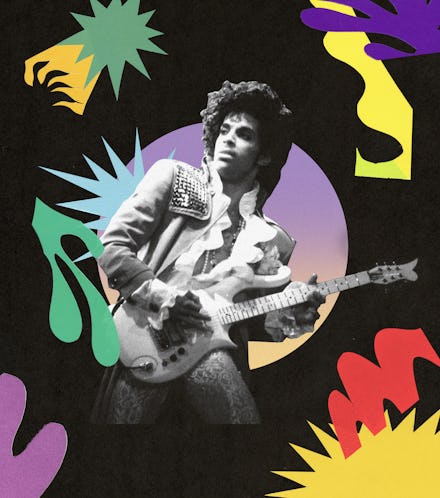

Prince spent the late 1980s on one of the most unpredictable and remarkable music tears the industry has ever seen. Having launched himself into megastardom after 1984’s hit movie and soundtrack Purple Rain, the mercurial artist spent the second half of the 80s showing the broadness of his sonic palette and affirming just how relentless his output could be.

After dissolving his famed Purple Rain-era backing band The Revolution in 1986, Prince released the double album Sign O’ The Times; recorded, then shelved, the dark Black Album; recorded and released Lovesexy with a new band; hit Europe for a major tour; and closed the decade with the double platinum-selling soundtrack for Tim Burton’s Batman. As the 1990s dawned, and as he settled in with a new band that would soon be known as The New Power Generation, Prince was as undefinable as ever. He began the 1990s with Graffiti Bridge, another movie and soundtrack; this time the film was a flop, though the album was another hit.

But critics believed that he was spreading himself too thin—a sentiment his label would soon echo. There was also chatter that Prince’s eclecticism was hurting him. There was a perception that Prince hadn’t made an album “Black enough,” “mainstream enough,” or “radio-friendly enough” in years.

“There’s nothing a critic can tell me that I can learn from,” Prince said to Rolling Stone in 1990. “If they were musicians, maybe. But I hate reading about what some guy sitting at a desk thinks about me. You know, ‘He’s back, and he’s black,’ or ‘He’s back, and he’s bad.’ Whew! Now, on Graffiti Bridge, they’re saying I’m back and more traditional. Well, ‘Thieves in the Temple’ and ‘Tick, Tick, Bang’ don’t sound like nothing I’ve ever done before.”

There was also the assertion that the daring artistry of Prince was being upended by the emergence of Hip-Hop, a genre the musical iconoclast had seemingly denounced on “Dead On It,” a lost track from the bootlegged aforementioned Black Album, back in 1986.

“Well, first I never said I didn’t like rap,” Prince would clarify to Sky Magazine shortly after his 13th studio album, Diamonds and Pearls, dropped in 1991. “I just said that the only good rappers were the ones who were ’dead on it’ — the ones who knew what they were talking about. I didn’t used to like all that braggadocio stuff. ’I’m bad, I’m this. I’m that.’ Anyway, everybody has the right to change their mind.”

Superstardom can be a tricky place for Black artists who refuse to be boxed in. Michael Jackson’s “King Of Pop” ambitions sometimes led him into musically banal territory in an effort to maintain his tremendous mass appeal; the milquetoast Paul McCartney duet “The Girl Is Mine” was released as Thriller’s first single in 1982 mainly to get that album on white rock radio. That is quite an ingenious bit of Trojan horsing, but that kind of preoccupation can neuter artists creatively.

Pop stardom can often be stifling of Black artistry, but after spending years expanding his musical repertoire stylistically, on Diamonds & Pearls, Prince offered a glimpse into how the Black pop auteur can navigate mass appeal and their own creative muse all at once. With megahits like “Gett Off,” “Cream” and the title track, Prince and The New Power Generation dropped his most radio-centric project in years. But it somehow sounded like nothing Prince had ever done before.

“No band can do everything,” said Prince in 1991. “For instance, this band I’m with now is funky. With them, I can drag out ‘Baby I’m a Star’ all night! I just keep switching gears on them, and something else funky will happen. I couldn’t do that with the Revolution. They were a different kind of funky, more electronic and cold. The Revolution could tear up ‘Darling Nikki,’ which was the coldest song ever written. But I wouldn’t even think about playing that song with this band.”

Sure, there were glimpses of him embracing new jack swing elements on the Graffiti Bridge soundtrack and bad attempts at rapping on tracks like “Alphabet St.” and “It’s Gonna Be A Beautiful Night,” but Diamonds & Pearls is where Prince fully melds Hip-Hop sampling and attitude into his New Power Generation sound. His distinct LINN drum machine was tossed aside, however, replaced by the thunder and groove of Michael Bland and newer, harder Bomb Squad-esque beats.

And he finally had a band that could keep up with it all.

“The New Power Generation is a band Prince doesn’t have to babysit,” rapper Tony M, a member of the band, told SPIN in 1991. Bland, keyboardist Tommy Barberella, bassist Sonny T. and rhythm guitarist Levi Seacer, along with powerhouse vocalist Rosie Gaines—they formed the core of Prince’s newest, tightest musical unit. On Diamonds & Pearls, Prince somehow manages to embrace sampling and hard beats while also producing a sound that was his richest and most musical to date.

“Everybody else went out and got drum machines and computers,” Prince told SPIN. “So I threw mine away.”

There are contemporary artists who follow in that spirit of mass appeal and musical eclecticism. Frank Ocean has, despite his limited output, been able to sustain his wide appeal while also challenging his audience to follow his creative sojourns into everything from emo ambient grooves to Beatle-esque pop psychedelia. Janelle Monae can deliver shiny hooks with the best of them, and also carry her audience through heady Afro-futuristic concept albums. And, of course, it cuts both ways; Kanye West has never been lacking a muse and follows his own creative path, but Ye has been both revered and widely criticized for the inconsistency of his musical output post-2011, largely because it seems so unfocused and non-linear.

But artistry won’t stay stifled. Prince’s body of work, during his most creatively fertile period, stands as testament to mastering a fiercely individualistic creativity and pop appeal.

"I can't wait four years between records,” he’d say to USA Today. “What am I going to do for four years? I'd just fill up the vault with more songs."

Diamonds & Pearls wasn’t Prince’s return to pop hits inasmuch as it was him solidifying the talents of his new band and shoring up his spot as a new decade dawned. A Black artist in full command of his art, still capable of delivering big radio hits, is something that we now see more consistently; but in 1991, only a handful of acts had gotten to that place. Prince was one of them, and he proceeded to rewrite the rules when he got there. In 1991, he was at the top of music; 30 years later, his legacy remains there.