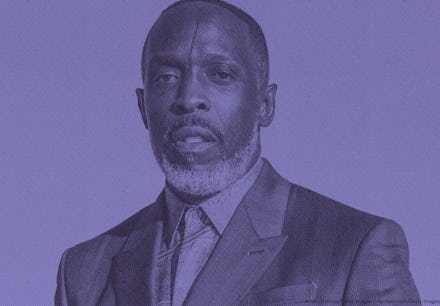

The unmatched power of Michael K. Williams

There’s a certain responsibility and pressure inherited by males born in Brooklyn. Although the same could be said by any New York City resident, there’s only one County of Kings. Heavy is the head, but it’s the mindset that the crown bejewels. Those from the “thoroughest borough” have no choice but to think big. Brooklynites would rather die young and enormous than live dormant for decades. Michael K. Williams was not spared these seismic expectations.

He was born and raised in an East Flatbush neighborhood that was unattractive to interlopers and hazardous to its population. Worse, he was raised in a project in the Big Apple during its volatile decades. You don’t climb out of a generation of public housing wrapped in West African melanin without first accepting your king’s disease. After 54 years on earth, Michael K. Williams died on a throne. But he spent the majority of his life searching for an escape.

Like many inner-city youth, Michael was void of direction. The hood lies loudest to a Black boy. Nevermind a path towards royalty, there were times when the son of West Indian and American southern parents thought the only route was downhill. He tripped often. He saw himself in the lost boy running throughout the dark warehouse in Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” video, and immediately accepted that his calling was to entertain, venturing to become a backup dancer. Yet, he could not outrun his legacy. Even when it ran him square into the blade of a razor on his 25th birthday. That was 1991, the year Michael began to realize that he was done being a caterpillar.

There’s an arrogance that one must possess to become who they are supposed to be. They must adopt an almost delusional state while pushing forward. Michael and the 150 stitches that would forever tattoo his face never missed an audition. He credited it to his “Brooklyn state of mind.” The bravery to make vanity obsolete in a business fueled on superficiality took him around the world with pop Gods like Madonna and George Michael. It was on the set of George Michael’s video “Killer” where the upstart finally found his golden path. After repeated pleas from director Marcus Nispel to emote, Michael realized he was being instructed to use that big Brooklyn heart of his. That was the first time he fully comprehended what it meant to act.

Michael’s scar would still lead the way. It’s what grabbed the attention of the late great Tupac Shakur. While hunting for an actor to play his younger brother in the 1996 film Bullet, Shakur found himself transfixed by Michael’s headshot. By the turn of the century Michael had separate films with Pac and Martin Scorsese (Bringing Out The Dead) under his belt, as well as guest starring roles on Law & Order and The Sopranos — of which he pridefully beamed to have never been killed off. Of course, sharing scenes with HBO’s biggest Tony allowed him to find his throne by placing a crown on a homosexual stick-up kid from Baltimore.

Critics lauded Omar Little, Williams’s portrayal of real life Baltimore murderer Donnie Andrews, because of the character’s contradictory behavior as someone who robbed drug dealers while still displaying unshakeable morals. But Omar was never contradictory — he was rigidly coded. What many outside the Black community misconstrue for a person of color’s instability is simple nuance and complexity. That’s what Michael gave our television reflections: dimension. A reminder that whether on or off screen, Black people are no monolith. To bring Barack Obama’s all-time favorite television character to life is no small spell. Your craft must possess some royalty. Royalty earned en route.

Although Omar is a fan favorite, Michael may have been more frightening on the sterling 2016 series Night Of. Using vulnerability and sensitivity as both a launchpad and compass for Omar’s altitude forced viewers to fall in love with the trench coat rockin’ Robin Hood who robbed hoods. In Night Of, Freddy Knight was all callous. When you bring both characters into one and slingshot him back about a century, you have Boardwalk Empire’s Chalky White. For a Black man to survive in America, it takes heart. For a Black man to stand tall in open view and opposition of White America demands more than any music video director could ever summon. It’s what places Omar and Chalky in a light shared by fictional heroes like the countryman Deadwood Dick, or Furious Styles, the inner-city father from Boyz N The Hood.

He credited his method to two giants. First, was Mel Williams (no relation), his teacher at the Philadelphia School of Arts. When the two first met, Michael’s formal teaching had been primarily European. It was professor Williams that instructed him to build every character he aims to embody off of his personal experience as a Black man — regardless of the character’s race. It was a necessary shedding in order to manifest his very own kingdom.

Michael brought that clarity to much of his work, including to his 2020 role in the sci-fi series Lovecraft Country as Montrose Freeman, a man desperate to protect his son from generational trauma, supernatural and otherwise. This was one of those roles that made the Michael K. Williams we all knew and loved.

The second giant was Denzel Washington. Michael heard the GOAT reveal that whenever he prepared for a role, he summoned the ancestors to bring the character to him. If you ever saw Michael dance, you understand that Washington’s wisdom spoke to the actor in both stereo and technicolor. History will concur that once he paired Denzel’s words with the "black man first, actor second" approach, Michael K. Williams would never again be stopped by anything but those ancestors. They would give him his crown and eventually his escape.

Theater instructors will proclaim that for an actor to bring a character to its full potential, they must first let it possess them. They’ll say acting is an out- of- body experience—but it’s only good acting that requires a body high. Michael K. Williams had the power to bring a singular set of flesh and hue to Black men, whether they were chivalrous, closeted, mourning, or doomed.