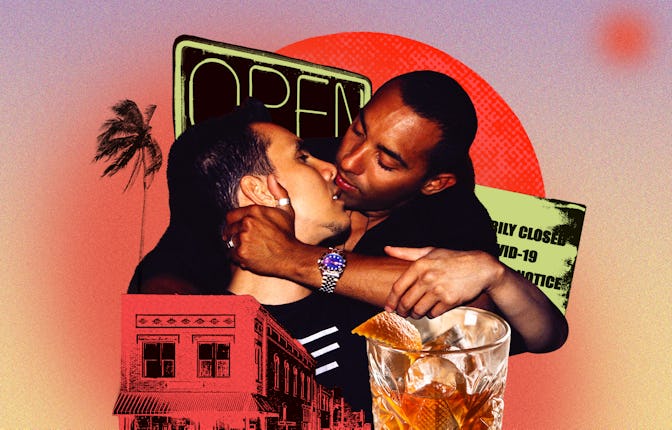

Gay bars have been closing en masse. Maybe that’s a good thing.

Perhaps we can finally build truly queer-friendly spaces in their place.

In the summer of 2020, I donated money to keep some of my favorite queer establishments open. The future looked grim back then, and the general consensus was that COVID would probably spell the end of many already-struggling gay bars.

Two years later, some of the bars and clubs I loved did indeed close, while many others miraculously survived. But in the year since I’ve personally added gay bars back into my social repertoire, something about them has felt lukewarm. The same, tired scene plays out pretty much every time I cross the threshold: Shirtless men with abs look me up and down, there are seldom any queer or trans women present, and people of color are often belittled. In fact, just last week at a bar in Brooklyn, a gay white man made a bottom joke and pushed a cue stick against my butt cheek.

The problem isn’t that gay bars have changed post-pandemic; it’s that they’ve stayed exactly the same — even though the world, or at least our collective conscience, has finally changed. LGBTQ+ rights are under attack, Black trans and nonbinary people are being murdered at unprecedented rates, and white supremacists are storming drag queen story hours. But you wouldn’t have an inkling about any of it within most gay bars, where the main concern among patrons seems to be who looks fuckable enough to take home.

Don’t just take it from me: Many queer people know that if you’re not a specific “type” of attractive (cis, male, and white), you’re basically irrelevant or disrespected the second you enter a gay bar. In fact, it’s a huge plot point in the recently-released Fire Island movie. “The first time I went to a gay bar (in D.C.), I was called ‘Fish’ in line and my crotch was grabbed later that night,” Lisa Guraya, a 25-year-old account supervisor, tells me. “Every time I am at a gay bar I’m shoved into or bumped literally like I’m invisible, and it’s hard to not feel like I’m invisible because [gay men] don’t want to fuck me.”

The problem isn’t that gay bars have changed post-pandemic; it’s that they’ve stayed exactly the same.

Guaraya says the rejection she experiences in gay bars is multi-faceted: As a queer woman, she feels like the only women who are welcomed in those spaces are, ironically, straight. It’s happened to some of my lesbian friends as well; they walk up to another woman at a gay bar, only to find out said woman is just there with their gay male friend or a group of fellow straight women. Unless she goes to a bar that’s specifically for lesbians or queer women, Guraya says she can never assume that women at gay bars are actually gay. This wouldn’t be quite so tragic if not for the fact that there are currently only 15 or so lesbian bars in the entire United States.

Even though I’m a gay man, I can relate to Guraya’s feelings on some levels. Multiple surveys have shown that Black and Asian men are typically the least desired groups in the gay community — as an Asian person, I can attest to this. When I first stared going to gay bars, I felt invisible to most of the men there, unless they had some weird Asian fetish. On one occasion, at a bar called The Boiler Room, an older man walked up to me and told me he was a “rice queen,” expecting me to be flattered by such a horrendous pronouncement. The worst part: I remember actually feeling flattered that someone was acknowledging me.

But these types of racially-charged interactions eventually leave many people of color feeling horrible about themselves. “Once, this group of white gay men kept looking at me and my friends and at first I was like, ‘They want us,’” Brandon De Martinez-Mijangos, a half Mexican 20-year-old student at the University of Michigan, tells me. “But then they kept staring at us with dismissive looks, kind of like they were bothered by our presence. One of them came up to me after a while and said, ‘My friends were guessing which country you were from.’”

“A lot of the spaces that call themselves queer are just for white gay men, which is fucking sad because they’re supposed to know what oppression looks like.”

When news of gay bars closing en masse started spreading in the past couple years, many of us, naturally feared we would have nowhere else to go. That’s not entirely true, though. When the Black Lives Matter movement reached a fever pitch back in 2020, many people within the LGBTQ+ community began paying attention to the disproportionate burden of violence faced by Black and brown trans people; since then, we’ve seen the rise of collectives like the Providence-based dance party Que Dulce, created as alternative spaces for LGBTQ+ people of color. “We wanted to challenge what a queer space could be,” Atlás Kidvai Alvarado, a 26-year-old nonbinary designer and co-founder of Que Dulce, tells me. “A lot of the spaces that call themselves queer are just for white gay men, which is fucking sad because they’re supposed to know what oppression looks like. Also, these gay white spaces just play pop music and I’m like, ‘Where’s the reggaeton?’”

I do get a little sad thinking about the fact that the prejudice of dominant gay spaces is so strong that it’s caused a physical rift in our community — a rift so powerful that some of us have renounced mainstream gay spaces all together in favor of separate gathering spots. “Men of color may feel identity-based pressure and stress when they are desired only insofar as they hew to racial stereotypes, such as the submissive Asian bottom and dominant Black top,” Russell Robinson, professor of law and faculty director of the Center on Race, Sexuality and Culture at the University of California, Berkeley, tells me. “Men who do not see themselves in that light may struggle to find partners who accept them for who they really are. To some extent, segregation in the gay community and gay bars in particular reflect broader social segregation in society.”

But not everybody agrees with my perspective that gay bars should be easy, lovey-dovey spaces where everyone can coexist peacefully. “In this age of isolation, of Instagram, we remove our bodies from serendipity, frisson, even awkward encounters — learning from a misunderstanding, meeting someone who changes your mind,” Jeremy Atherton Lin, author of Gay Bar: Why We Go Out, tells me. “When I hear the term ‘inclusive queer spaces,’ what comes to mind is an echo chamber. What comes to mind is sites that are actually exclusionary in some way — no bachelorette parties, no jocks, whatever rules like that.”

I grew up loving and finding my identity in gay bars, and there will always be something beautiful about their seediness, their unhindered expression of sexual desire, and their chaos.

I actually get what he’s saying: I grew up loving and finding my identity in gay bars, and there will always be something beautiful about their seediness, their unhindered expression of sexual desire, and their chaos. I’ve also had my fair share of verbal altercations at gay bars, all of which made me more open-minded and helped me fight for my rightful space in them. But I disagree that using the lexicon of “inclusive queer spaces” will turn these bars into echo chambers — in many ways, the fact that gay bars haven’t evolved at all is a testament to the fact that they already are echo chambers.

But when I ask Atherton Lin what his ideal gay bar looks like, I realize we don’t disagree as much as I thought. “I suppose my ideal gay bar would be a gay bar that isn’t idealistic,” he says. “A place where people are patient, and forgiving, and open. Maybe if we don’t hold one another to particular ideals, we can actually discuss some interesting ideas.”

As far as I’m concerned, the gay bar as we know it probably has to die. Its survival will be contingent on its ability to reinvent itself as a space for queer and trans people of all races and body types. It’s time we reimagined gay bars not only as spaces where we can find our next hookup, but also as places conducive to meaningful connections that aren’t solely tied to our fuckability. I don’t think I’m being too idealistic when I say that it’s those queer connections that will get us through our next bout of COVID, comfort us after a fight with a homophobic uncle, and lead us toward a queer future where we can all be in one space, together.