I wrote a book about Black queer joy and pain. It's already been banned in 10 states

My fight is one of tradition, not of chance.

Around the age of eight, I learned that Phillis Wheatley was the first Black American to publish a book of poetry. What most teachers left out of that story was how hard America made it for her. She had to go to court to prove that she had actually written the poetry. Even after proving her case, she was still denied the right to publish because, well, she was Black.

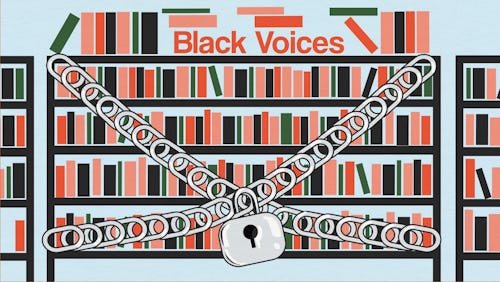

It’s been seven weeks since my memoir All Boys Aren’t Blue has been banned in now more than 10 states (with one criminal complaint discharged but the potential for more on the way) — and I realize that my fight is one of tradition, not of chance.

My book, which explores themes crucial to today’s marginalized young people, came out about a year and half ago and has steadily been gaining traction. When I found out that a group in Kansas City, MO was attempting to have All Boys Aren’t Blue banned in several high school libraries, I initially laughed it off. Not because it was funny, but because I was right. I knew, at some point, this day would come.

A story like mine has never been deemed “appropriate” reading material. The honest coming-of-age story of a Black queer boy trying to navigate a world that oppresses him was just not something I ever thought white parents, especially, would want their teens reading. And why on earth would conservative school administrators want their students to know about people like me, whose experiences, pain, and joy has moved society forward? In their minds, I deviate in an ugly way. And that warrants erasure.

The banning of my book, for better or worse, has historical precedence. Between the 1490s and 1865, millions of Black folks lived in America as enslaved people and yet we have a little more than 6,000 accounts of their story. And book banning was borne of this insatiable desire to snuff out Black literacy.

In America, that privilege of reading and writing was only afforded to white people — with very few Black people allowed that opportunity during slavery. Many stories of enslaved people who learned did so in secret, since you could be punished by death for teaching a Black person to read. See, they believed that if our stories didn’t exist, it’s as if we didn’t exist. If we couldn’t be literate, they’d own us forever. Residuals of this still haunt us today.

Slave narratives that did make it to print were heavily criticized, censured, and shamed during the 1800s by most white men in power. Blotting out enslaved people’s words was to blot out their humanity. Denying our books was to deny the brutality of slavery.

Amidst the widespread attempts to ban my story, I can’t help but reflect upon others who went through it. Some of the greatest American writers in history — Toni Morrison, for example, had at least one of their books banned while white writers like Laura Ingalls Wilder’s works remain on shelves despite its racist, anti-Black tropes.

Alongside the racial erasure, the ban on my book is fueled by a fear Black queer storytelling. My story, and others like it, reveal unvarnished truths about what it’s like to exist in multiple marginalized spaces. This fear of stories that hold a mirror up to the oppressor is so strong that it’s persisted for multiple generations.

If I were a white queer person who wrote the same book, I would likely be heralded as the next Walt Whitman. Be very clear: There are white queer stories out there with the same (if not more) “graphic” material, but these books are not being called into question. Also, my story is no “heavier” than ones that straight white people have dropped, unbothered, for centuries. Black queer people deserve a safe space too.

There’s a lot to be said about your name being linked to a work that people are trying to extinguish — one that vividly paints a picture of Black queer humanity. Although this fight feels heavy, (and I know more resistance will come), I am strengthened by the fact that my ancestors prepared me for this time and time again. I feel both powerful and empowered when I connect with people who my work has inspired — especially the students who are fervently raising their voices in my story’s defense.

It does hurt to see this effort to deny people the right to read stories about their own experiences. My book would provide comfort to people who are constantly reminded by society that they are lesser than — that their voices and stories don’t matter.

Despite the attempts to thwart stories like ours, the ban-instigators won’t win. I am an author who decided to tell their Black queer story so that others could feel seen in the ways I didn’t as a youth. Trying to deny my story won’t deny my existence. And I’ll do my best to make sure those who need my story will get to read it. And there ain’t a damn thing anyone can do about that.