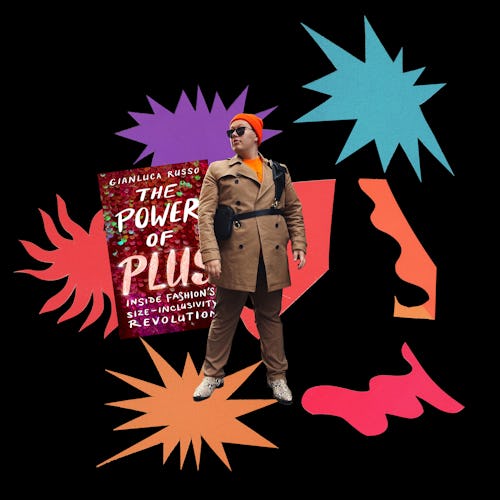

The Power of Plus author Gianluca Russo wants fashion to face its toxic, fatphobic tendencies

“This industry is still incredibly far behind from where it should be, and if we don’t talk about that and analyze that, what are we doing for future generations?”

Growing up in the 80s, it felt like I was taught to hate myself and be ashamed of my body, thanks in large part to TV shows and women’s fashion magazines that idealized a very specific (read: thin) body type. And then, around 2013, I discovered the “body positivity” movement through online spaces like LiveJournal, Tumblr, and Twitter. That discovery was pivotal for me — not just because of what I learned, but also because of who I met. I found a community, one I’ve remained a part of since then. Almost 10 years later, it was through these spaces that I met journalist, community builder, and newly minted author of The Power of Plus, Gianluca Russo. Through the depths of the Internet, we found one another and bonded, both as members of the plus-size community and as writers living through the social media evolution of body acceptance and fat activism.

By that point, brands like Dove and Aerie had made decisions to use models of all sizes and abilities in their advertising campaigns, increasingly more TV shows were debuting featuring plus-size leads, and models like Tess Holliday and Ashley Graham were gracing the covers of mainstream fashion magazines. Fresh out of college, Russo was relatively new to the media and fashion industries, but he was consistently pushing the boundaries for something more. In a short period of time, Russo established himself as a voice to be heard, making an appearance on Project Runway, sitting front-row at New York Fashion Week, landing a column on fat discrimination in NYLON, and pushing the fashion industry to engage in difficult conversations when it came to plus-size bodies. While reporting on topics like fatphobia at work and the lack of menswear in plus, Russo also built his own virtual community (co-founded by fellow journalist Shammara Lawrence), named The Power of Plus, that’s grown to more than 15,000 people so far.

But he wanted to go even further. “After a few years of writing all these magazine articles, I wanted to do something bigger,” he tells me over Zoom. “[Something] that felt like a more grand celebration of all these women and men and people who had been able to create such a profound movement over the years.” Russo manifested that goal in his debut book, The Power of Plus, which hit shelves today. The Power of Plus expands on the conversations Russo has already been having, providing an inside look into the inception of the plus-size market, the anti-blackness and diversity issues that still run rampant within the community and fashion industry, the sorely overelooked men’s plus-size category, and so much more. The book reads as a collection of stories told by some of the most prominent change-makers and notable voices in the community, including creative consultant and writer Nicolette Mason, The Curvy Fashionista creator Marie Denee, writer and model Kendra Austin, and designer Christian Siriano.

Russo tells me The Power of Plus was his way to celebrate the body positivity community he’s so deeply entrenched in, but also the fashion industry that he truly believes can change for the better. Ahead, Russo discusses writing this book from a place of radical transparency, his real feelings about the word “fat,” and his hopes for the future of plus-size fashion.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.

In your book’s introduction, you wrote, “I know change is real. But change is still new. And the only way to push forward is to offer unfiltered transparency.” Why do you think it’s important to offer such radical transparency?

I’ve seen in our digital age that often, we’re only offering a highlight reel of what we've been able to accomplish, and it does a real disservice to the movement as a whole. I think we're at a point right now where things have remained stagnant for a while and until we can offer up a level of transparency and nuance to these conversations, we can't push forward because people simply don't understand what's going on behind the scenes. If we're only celebrating the small wins here and there, what are we doing to push [against] the lack of change that is happening? This industry is still incredibly far behind from where it should be and if we don't talk about that and analyze that, how can we push forward from there, and what are we doing for future generations? What are we doing for the future of fashion? We're really not helping; we're only putting a BandAid on the problem.

“Often, we’re only offering a highlight reel of what we've been able to accomplish, and it does a real disservice to the movement.”

Something that you did in your book, which I’ve personally never seen done before, was include roundtables with others in the industry. Why did you do this, and how did you decide on the topics and individuals to include?

What I wanted to do was set up larger sections of the book with these overall conversations. To me, each chapter is about a particular point of view, discussing a particular topic. These individuals are all there to really discuss these topics with me. When I look at the book, I see it as three sections: the past, where we are currently, and the future of plus-size fashion. For me, these roundtable conversations gave readers a sense of where the industry is at. I didn’t want to write a history book, and I didn't want to write something that was solely social commentary. I wanted to write this piece of narrative non-fiction that kind of brought us through time together, through our own perspectives. I think that helped to break it up and show people, we’ve come such a long way, and this is where we are now, and this is how far we still have to go.

I think that’s so important. In the chapter “The Body Boom,” you wrote about Old Navy’s decision to expand sizing, only to later pull plus-sizes from some stores. So to your point, there’s still a lot of work to be done, and this push-and-pull of excitement over expanded sizes followed by disappointment over pulling those sizes showcases that we’re not doing enough.

Right? I mean that's the problem! There are so many different layers, and there is not one person or issue at fault here. The conversation is so nuanced. Old Navy is actually a great example because they are a brand that made a huge splash, and so many people knew them and loved them. Yet still, they weren’t moving product. Why was that? But you know them pulling [expanded sizes out of stores] is not going to get painted like that. It’s going to be seen as them giving up on the plus-size community, but I don’t look at it that way. I look at it as a re-adjustment. At the end of the day, any business has to make re-adjustments to their business to meet and match demands, so that’s what they are doing. I think that's what was really eye opening to me, too — getting an inside look at these brands that I hadn't had access to before and really understanding that they are all struggling, even the brands that are presenting themselves as being successful. I think that's why transparency is important, because all these brands are putting up a facade. They're [pointing to] numbers [like] “68% of American women [wear over a size 14]” or “[the plus-size clothing market is worth] $24 billion” — but the reality is, they're saying you can do it and behind the scenes they're struggling. They’re all struggling.“The conversation of racial diversity is fundamental to the conversation around body diversity.”

You’ve made a point of also discussing the issues of race and diversity in the plus fashion industry. Why do you think the fashion industry — and more specifically, the plus industry — still struggles with this?

I think the conversation of racial diversity is fundamental to the conversation around body diversity. I made sure it was incorporated into every chapter, and I wanted to make sure it was clear that I was incorporating all these different lenses on diversity into every chapter. [But] I knew I needed to dedicate an entire chapter specifically to anti-blackness and colorism within the industry, because of how much it dates back to the origin of plus-size fashion and body positivity, which started in the 1960s by the fat activist movement. It's a problem that has existed since the conception of body positivity. One of the biggest problems we're seeing right now in the industry is tokenization, anti-blackness, and the lack of a spectrum of diversity. There is so much nuance in the conversation that I didn’t want to put my own personal lens or perspective on, so the chapter in the book [titled “The Racial Divide”] is very guided by the voices in it. I didn't want to offer my own social commentary from my own personal perspective on that — specifically the chapter about tokenization. That chapter and conversation regarding race, size, and gender and how it all intersects is so crucial to every part of this movement. Diversity is at the core of this conversation and movement.

I loved the way you talked about the word “fat” and the weaponization of that word. Talk to me about writing that chapter and your own relationship to that word.

Yeah, I think in recent years we've seen the value of identity and how we self-identify. I think that's especially true in the body diversity space. What I've seen is that people have very different opinions about the word “fat” and the different ways they want to be labeled or not labeled. There's a lot of anger attached to it, and there’s just so much emotion in years of ridicule and trauma around these words. But people should, in my opinion, be given the space to choose [the label] they prefer, whether that's “plus-size,” “curvy,” or no label at all — which a lot of people do gravitate toward. We shouldn't make [people] feel like they can't be a part of the community because they don't want to use the word “fat.” [That said], as I was writing the chapter, I wanted to include my own personal experience, which of course is a bit intertwined throughout the book. I wanted to show readers how my perspective was being molded and changed by the people I was meeting and including. Heck, many of the people who will read the book will never have read my work before, so I wanted to show them that by writing this book, my view of certain terminology and certain topics was being changed and shaped, and still is.

“I know what's at stake and what needs to be done. But being armed with that knowledge is how I feel prepared for the future.”

In your chapter, “Curse of the Token Curve Girl,” you give readers a look at just how toxic the fashion industry is. For people picking up this book, what do you hope they take away, and for those in the fashion industry, what do you hope they’ll change?

First off? I hope they love that chapter, because that is my favorite chapter. I hope people who read this book understand that we have come a long way. There's no denying that. I hope they feel like we've accomplished a lot together, but I hope they see that there is still an infinite amount of work to do, which can seem intimidating at first. I want people to feel inspired. I want them to feel proud of how far we've come, but I want them to feel hopeful for the future. I know what's at stake and what needs to be done. But being armed with that knowledge is how I feel prepared for the future.

I wanted to arm these readers with the knowledge of where this industry is, and how we can get to the future by using examples of the past. Looking at people like [legendary plus-size model] Emme and the trail she was able to blaze in the 1990s, we don't have to just forget about her work. We can honor her work, and then use the ways she was able to attack the industry as our new action points for the future. For me, that was the most exciting part of [writing the book] — being able to put the pieces together, to look at 1990 to 2020 and say, “This is how everything fits in. This is how it's one story, and not a bunch of different stories. This is how we're all contributing to the same narrative in our own individual ways.” My ultimate hope is that people will see the special and unique ways they can make change that all contribute to our community goal of size equality.