A 99 million-year-old "hell ant" was found in amber murdering its prey

2020 is shaping up to be one hell of a year. On top of murder hornets and zombie cicadas, we've now got a thing called hell ants. The hell ants, mercifully, are not alive, but a new study about one specimen trapped in amber has revealed details about how they operated, and what exactly made them so hellish. Published last week in the journal Current Biology, lead author Dr. Phillip Barden and his team described a creature with mandibles that snap together vertically rather than horizontally like modern-day ants. This unique mandible allowed the ants to pin victims against a horn-like appendage on its head.

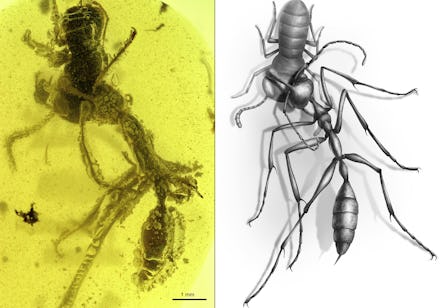

That's exactly what's happening within the amber, where a hell ant is frozen in the middle of clutching its prey — an ancient relative of the cockroach. The fossil is estimated to be around 99 million years old, and has offered a rare glimpse into the behavior of these prehistoric ants, lead author Phillip Barden said in a statement. Paleontologists are often left guessing how an extinct creature might've behaved while hunting or used its unusual appendages, but this amber left no question about how the ants used their mandibles.

"This fossilized predation confirms our hypothesis for how hell ant mouthparts worked," Barden said in a New Jersey Institute of Technology press release. "The only way for prey to be captured in such an arrangement is for the ant mouthparts to move up and downward in a direction unlike that of all living ants and nearly all insects."

There used to be a variety of prehistoric hell ants around during the Cretaceous Period, but many of them died out over millions of years as ants with horizontal mandibles proved to be better suited for survival.

"This fossil reveals the mechanism behind what we might call an 'evolutionary experiment,' and although we see numerous such experiments in the fossil record, we often don't have a clear picture of the evolutionary pathway that led to them," Barden explained.

What might've doomed the hell ants is the very thing that makes them unique. The researchers predict the ants couldn't move their heads very well because of their strange mandibles, and that it's possible they had trouble getting nutrients from their prey.

"We originally thought that all the hell ants would have pierced their prey and drunk the hemolymph, which is like insect blood," Barden told Live Science. But that didn't appear to be the case with the fossilized sample they have. The ant's horn wasn't stabbing the prey, just holding it in place.

Another hypothesis is inspired by the Dracula ant, a fierce modern-day ant that can snap its mandibles at a speed more than 200 miles per hour. The mandibles of the Dracula ant are very strange, just like the hell ants', which can offer an explanation into how the ancient insects might've fed.

"They have these highly specialized mouthparts that are so exaggerated they can't feed themselves," Barden explained to Live Science. "Instead, they feed the prey to their own larvae — and the larvae have unspecialized mouthparts, so they can chew normally."

The larvae of the Dracula ant then feed on the prey, getting their nutrition. Once they're full, the adult Dracula ant makes cuts into its own offspring and drinks the hemolymph — a process called non-destructive cannibalism.

"Basically, they use their own siblings and offspring as a social digestive system," Barden said. "We don't have direct evidence that's the case here, but that could be something that's going on."

The researchers aren't 100 percent certain the ants died off because of their feeding habits, however. Questions still remain as to why the prehistoric ants with oversized mandibles died but modern ants with oversized mandibles survived. Barden and his team plan to continue their research into how certain species avoid extinction and why others couldn't do the same. It's an important question to study and answer, said Barden, as the Earth undergoes its sixth mass extinction event.