The U.N.’s big climate conference is missing some key voices

It’s nice that world leaders are talking climate. It’s not so great that that means it’s a lot of white men.

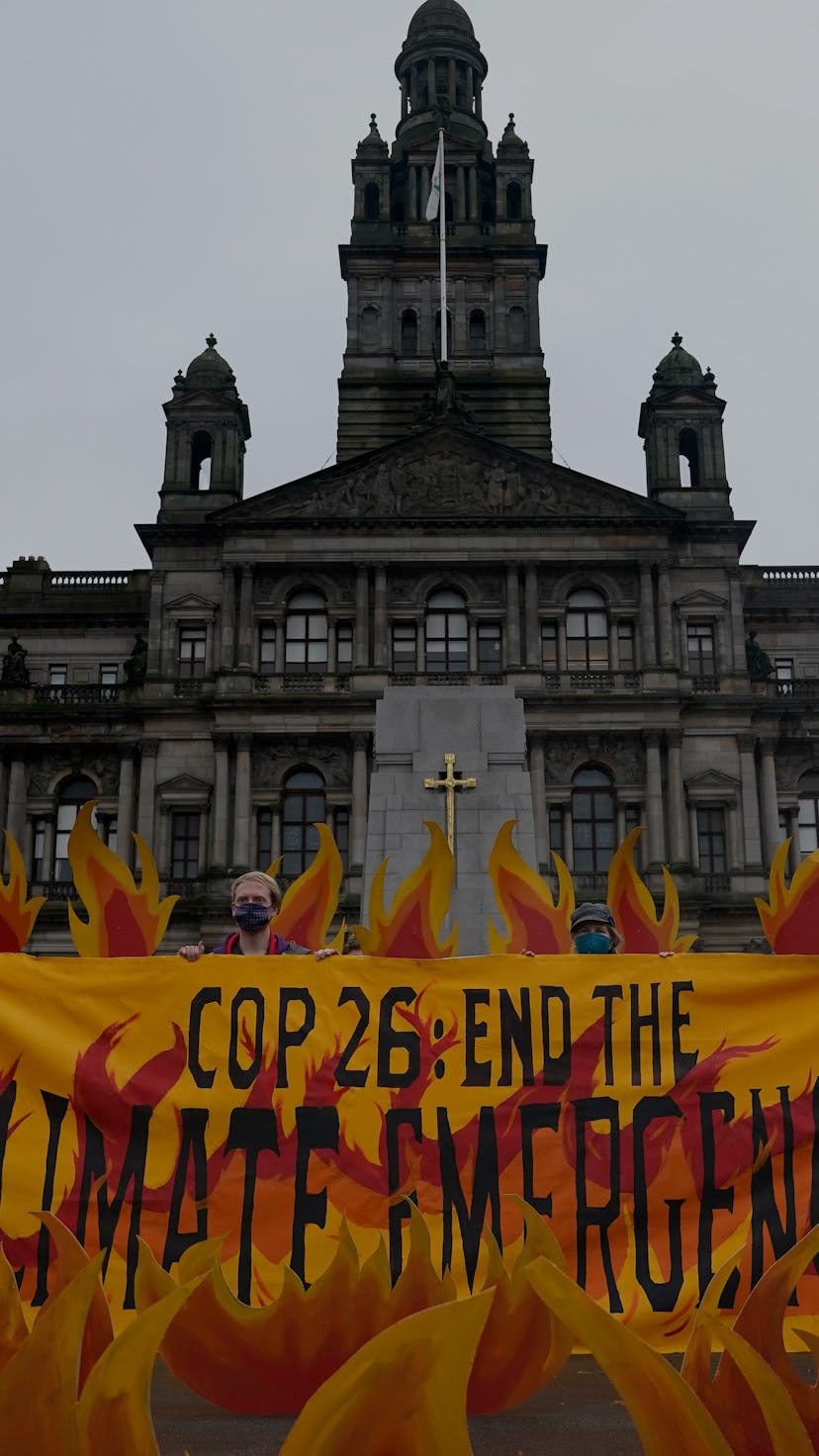

This week, world leaders descended upon Glasgow, Scotland, for the 26th U.N. Climate Change Conference (COP26). Roughly 30,000 delegates from nearly every country in the world will spend two weeks talking, debating, and hopefully coming to recognize just how crucial it is to take rapid, meaningful action against climate change.

The annual event, held in a different city each year, has produced some of the most consequential climate-related policies in history. In 1997, the Kyoto Protocol set the groundwork for greenhouse gas reduction. In 2015, the vast majority of the world ratified the Paris Climate Agreement, which set up the framework for preventing the planet from warming to potentially disastrous levels. And yet, COP26 seems to have a particular sense of make or break. It’s the first conference following a global pandemic, and the first to be held during the most consequential decade in the fight against climate change. The window is closing, a major shift must be made by 2030, and plans agreed to at the conference will be key in meeting the moment.

That’s why it’s so disappointing, if not downright troubling, to see how many crucial communities have been left out of the discussion. On the largest stage in the world, on the most important challenge of our time, the U.N. and the nations of the world are still failing to hear from Indigenous populations who protect our planet, women who will be the most adversely affected by the worst impacts of climate change, and the youth who will be taking over this planet right as its problems peak.

“We are in a time where we need healing — not just our planet, but all of us as human beings,” Ben Yawakie, a climate justice organizer at the Indigenous-led NDN Collective and a member of Minnesota’s Environmental Quality Board, tells Mic. “We’ve been so disconnected from our Mother Earth that we are living in a time that is seeing our world fall apart ecologically and philosophically.”

While the United Nations has been talking climate change for decades, it has too often ignored groups that are disproportionately affected by an impending climate disaster. It took more than two decades of climate conferences for the organization to establish the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), formed in 2007, to address the concerns of Indigenous communities. In 2009, the U.N. established the Women and Gender Constituency to make sure that the voices of women were heard. It wasn’t until earlier this year that the U.N. created the Youth Advisory Group on Climate Change to give more influence to the generations that will actually face the worst conditions, especially if we falter now.

“Unequivocally” not enough

Yawakie says that the U.N. “unequivocally” has not done enough to consider Indigenous people in climate conversations. “Many of our Indigenous communities suffer the consequences of poorly guided international and regional policies that have direct impacts on our frontline communities,” he says.

Over time, Indigenous people have been largely displaced from their land. In the U.S., they have been pushed off nearly 99% of land that has historically been managed by Indigenous populations and onto land that researchers have found is more exposed to climate-related hazards and disasters. Similar forced or coerced movements have pushed Indigenous people worldwide into potentially dangerous living situations.

The displacement hurts the land itself, too. Indigenous communities preserve and protect essential ecosystems that we rely on for everything from food production to natural defenses from disease. As much as 50% of the world’s protected lands were once occupied or used by Indigenous communities, but they have been pushed out in the name of preservation. The results are often devastatingly bad; Indigenous people who understood the area and helped to maintain biodiversity are replaced by new occupants who often exploit the land and don’t properly care for it.

The U.N. has identified land restoration as essential to the climate fight, yet the community at the frontlines of the fight is often kept out of the conversation. Indigenous communities now own just 10% of the world’s land (significantly less than they historically have held), but that area holds nearly 80% of the world’s biodiversity.

“These policies are devastating to our communities.”

“How many Indigenous delegates are there? From the United States, there is Fawn Sharp, the president of [the National Congress of American Indians] and vice president of the Quinault Indian Nation. That is one person, up against governmental and institutional oppressors that continue to fuel conversations around false solutions,” Yawakie says. “These policies are devastating to our communities.”

They also ignore history, even fabricating a false one. “There’s a common thought that lands cared for by Indigenous people prior to European contact were untouched and pristine,” Yawakie says. “This sentiment is wholly incorrect. Indigenous people have cared over lands across Indian Country since time immemorial.” Practices once carried out by Indigenous people to preserve lands were banned by colonizers, only to produce worse outcomes. Forest fires, for instance, were once less prevalent thanks to controlled burn practices that Indigenous communities used. That practice was banned in places like California, dismissed as ceremonial and not practical. Meanwhile, wildfire risk has only grown due to mismanagement of these lands, despite research suggesting that controlled burns would benefit in many cases.

The gender divide

Studies also suggest that climate change will be particularly devastating to women. The U.N. has estimated that 80% of people who have already been displaced by the climate crisis — the result of rising tides, extreme weather, and other conditions that will make areas unlivable — are women. As the primary caregivers in many cultures, women are particularly vulnerable to food insecurity caused by droughts, heatwaves, and floods.

Despite this, Jazmin Burgess, the deputy director of the Inclusive Climate Action program at C40 Cities and Women4Climate, tells Mic that just 38% of delegates at the 2018 U.N. climate conference were women — and just 1 in 4 heads of delegations were women. “It is essential that women are at the table and involved in the decision-making at the highest level if we are to have successful climate action that empowers and builds resilience of women,” Burgess says.

It doesn’t help when the host country, which can set the tone for the whole event, falls woefully short. The United Kingdom sent a team of all-male delegates to COP26, failing to provide a single voice for the majority of the country’s own population. While they responded to the backlash by appointing a woman, trade secretary Anne-Marie Trevelyan, to the delegation, it shouldn’t require outrage to have women involved in the process. “It is incomprehensible that half the planet is not represented in the senior leadership team ... when it is widely acknowledged that the role of women is critical in tackling the climate and ecological emergency,” read a letter signed by more than 450 women activists, academics, and politicians.

“This approach is not only an ethical obligation rooted in the principles of equality — it also contributes to successful climate action.”

“If climate policies or projects are implemented without women’s meaningful participation and perspectives, this will only increase existing inequalities and decrease effectiveness as we will be perpetuating the last century’s bias,” Burgess says. This should be considered an unacceptable outcome, as we have historically failed many marginalized communities already. Climate change has made economic inequality worse globally, widened the gap of gender inequality, and made for an unstable social climate that produces civil unrest.

Listening to groups who are more likely to experience these outcomes will likely result in more action. “Women tend to make more long-term environmentally friendly decisions and are more likely to ratify environmental treaties,” Burgess explains. “Studies show that climate change risk perception and concern are higher among women than among men.” This, researchers believe, is driven by a number of factors, including the fact women are often more committed to social justice as a result of the women’s rights movement, and are more attuned to the risks presented by climate change.

Women can also be powerful agents of change, Burgess says. “Communities have a better ability to cope with natural disasters when women lead prevention, warning and reconstruction efforts,” she explains. “Women perform better at sharing information, mobilizing communities, and adapting. They also have a clear knowledge of the action that needs to be taken locally. This approach is not only an ethical obligation rooted in the principles of equality — it also contributes to successful climate action.”

The next generation

Central to all of this is young people. Across all populations, young people will be forced to confront the harshest realities of climate change if action is not taken. The next generation is already set to experience three times as many climate disasters as their grandparents, and are already feeling the harms in the form of climate anxiety and other psychological effects.

Even without a formal invite to the U.N.’s forums on climate change, young people around the world have managed to take collective action on the issue through organizing and protest. Youth-led groups have become some of the most vocal and effective drivers of political pressure, hammering politicians who ignore climate change and operating around the world without the same type of infrastructure that more established groups have. For young people, group chat and Zoom calls can be enough to drive meaningful action, even during a pandemic.

Youth groups have also managed to put on massive displays of support for climate action, realizing the looming threat to their future. Greta Thunberg’s climate strike motivated as many as 4 million kids across 163 countries to take to the streets and demonstrate.

The unfortunate fact is that while progress has been made in recent years to better include marginalized communities, COP26 risks a setback in representation. Yawakie calls the conference the “most exclusive” since the event’s inception, in large part because of COVID-19. The lack of vaccine accessibility for developing nations has resulted in some countries being excluded from the event. This is an inequality that will likely produce more of the same — with their voices unheard and populations unrepresented, countries with fewer resources will likely be an afterthought in conversations about addressing climate change.

Burgess says it is essential for more women to be included in the decision making process, both at these conferences and in governments around the world. Yawakie expressed concern about the U.S. delegation in particular, noting that it was likely unequipped to address the needs of marginalized communities like Indigenous people — a fear that appears to have been valid. During his speech at the start of the conference, President Biden made the case for market-based solutions as the primary force to address climate and pointed fingers at other countries while failing to fully acknowledge the U.S.’s outsized role in causing climate change.

“A success at the end of the conference would be a worldwide denouncing of fossil fuel extraction projects,” Yawakie said. With more voices from those most affected by climate change, this might be possible. Without them, it seems likely that we will fall short.