Democrats have put forward a less ambitious Green New Deal. Could it pass?

On Tuesday, Democratic members of the House of Representatives released a wide-ranging plan to tackle climate change, calling for investments in a renewable energy labor force and restoring and sustaining natural resources, like the ocean, among other demands. By creating climate jobs and mitigating pollution in all ecosystems, the plan, put forth by Democrats on the House Select Committee on the Climate Crisis, aims to reduce climate-related American mortality and achieve net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. It's reminiscent of the Green New Deal — though decidedly less ambitious.

Proponents of the new legislation, like Florida Rep. Kathy Castor (D), the chairwoman of the House climate committee, say that the sweeping plan is grand enough while also being tailored to meet the diverse needs of the climate. A signature element of the plan is employment, which is especially important now given the millions of Americans out of work due to coronavirus. "Our plan will put people back to work and rebuild in a way that benefits all of us. That means environmental justice and our vulnerable communities are at the center of the solutions we propose," Castor said in a press release.

This plan is a major step, and the most drastic step on climate that establishment Democratic congressional leaders have taken since President Trump's election in 2016. It also doesn't look so different from what younger, progressive legislators want. The Green New Deal, first proposed by freshman Rep. Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-N.Y.) in 2019 and later championed by the grassroots progressive organization Sunrise Movement, is founded on the tenet of environmental justice and touts the creation of renewable energy jobs. Both pieces of legislation approach climate issues from a number of perspectives, including agriculture, job creation, the wage gap, and the need for investment in low-income communities. Both proposals also note the increasing intensity and frequency of climate-spurred disasters, like wildfires.

Where the two plans diverge is time and scope. The committee's new plan is largely U.S.-focused in naming the sources and solutions of climate problems, while the Green New Deal names the U.S. as a main driver of climate change but lays out global goals for reductions in emissions. The Green New Deal calls for net-zero global emissions by 2050, whereas the House climate crisis committee's plan calls for net-zero U.S. emissions by 2050. The committee's plan calls for a 37% reduction in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 2030 and a 88% reduction in U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The Green New Deal calls for a 40-60% reduction in global greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.

But even the use of language like "climate crisis" and "environmental justice" in an official proposal championed by establishment Democrats is a stark contrast to the lack of urgency around climate change legislation that the party has demonstrated in years past. Just last year, when the presidential primary season kicked off, activists pressured the Democratic National Party for a climate debate, which party officials at the time believed was less important for a national audience than the issues of health care and how to beat Trump in the general election. A climate debate never happened, though a CNN town hall on the subject did.

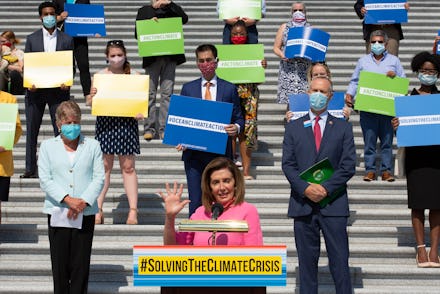

Activists may still be stung that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi was a staunch opponent of the Green New Deal just a couple of years ago. During her congressional orientation, Ocasio-Cortez visited protesters staging a sit-in at Pelosi's office on Capitol Hill, and a video of her speaking to young people holding signs like "Green Jobs For All" later went viral. That Pelosi has signed onto this proposal, just months before the 2020 election, is reflective of the work that activists and young voters have done to make climate change a defining political issue.

Tellingly, though, the committee's plan to tackle the climate crisis is undoubtedly inspired by the Green New Deal — but Ocasio-Cortez's legislation is mentioned only once in the 538-page proposal.

Politically, it's hard to say if one plan is necessarily better than the other. The Green New Deal launched and framed the conversation around climate change, at least from a real legislative standpoint. It was grounded in ideas of justice and has its roots in community organizing, but it was never even brought for a vote in the House. The committee's new legislation will likely be brought for a vote, on the other hand, and while it's not as far-reaching at the Green New Deal, it has a better chance of making its way through Capitol Hill given it's backed by establishment Democrats. For better or worse, the committee's proposed legislation is essentially a more moderate take on climate action, and therefore might be more palatable to centrist Democrats and even some Republicans.

The legislation has a strong chance of passing the Democratically-controlled House of Representatives, but it will likely stall in the Senate, where Majority Leader Mitch McConnell (R-Ky.) has long opposed climate legislation.