How to blow your nose without destroying the planet

Flu season is already miserable. Flu season on an overpolluted and dying Earth will be worse.

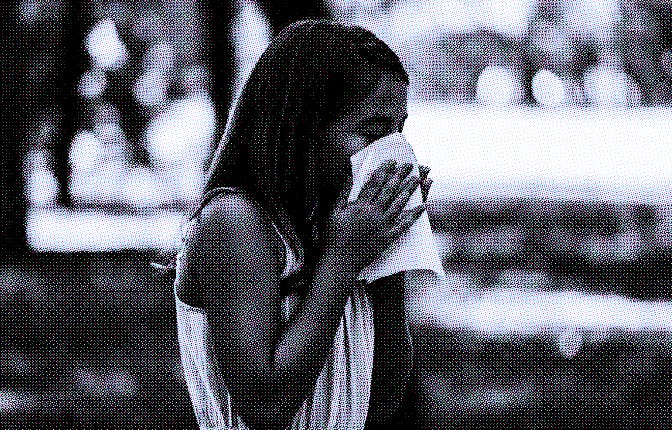

Feel the sniffles coming on? Whether you’re dealing with a flare-up of your allergies or cold season has finally gotten the best of you, odds are that when your nose starts running, you’re going to reach for the nearest box of tissue paper. Kleenex and other brands of facial tissue offer a kind of comfort when you’re starting to feel sick — a soft, gentle surface to empty all that snot into.

Americans have reached for these tissues when they are ailing for an entire century now, and we are not shy about burning through them. More than 255 billion facial tissues are used each year in the U.S., and that figure is only growing, both domestically and internationally. While the coronavirus pandemic had the unintended benefit of squashing other respiratory diseases like influenza — at least temporarily — it also led to a huge demand for single-use tissues. The fear of surface spread, which proved to be misguided, led to people abandoning reusable cloths and moving to disposable products.

While wanting to be sanitary and safe is a good thing, it’s also wasteful and has a significant impact on the planet. All those tissues have to come from somewhere. And in the case of most major facial tissue manufacturers, that somewhere is forests. According to the Natural Resources Defense Council, nearly 15% of deforestation is caused by tree-cutting done to produce paper products, including toilet paper to facial tissues.

Tissue demand in the U.S. alone has done major damage to places like Canada’s boreal forest, which is losing 1 million acres each year just to meet the demand of its southern neighbors. This is a big deal, warns Shelley Vinyard, the Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC)’s boreal corporate campaign manager, because the forest is “climate-critical” and “stores the same amount of carbon as twice the world’s oil reserves.” In the boreal forest alone, logging done for paper goods is responsible for an estimated release of 26 million metric tons of carbon dioxide each year. That’s the equivalent of dropping about 5.5 million new cars on the roads.

Vinyard also notes that on top of damaging one of our most important carbon sinks, cutting those Canadian trees is also messing up essential ecosystems. “It is home to hundreds of Indigenous communities whose cultures rely on the plants and animals of the forest,” she says.

Logging means that food sources dwindle, livable environments disappear, and species start to go extinct. The result is a loss of biodiversity, as only the most resilient species survive. Unfortunately, many of those species are disease carriers and spreaders. That means in chopping down trees, we’re also chopping down nature’s defense system against potential pandemics — and those tend to require a lot of facial tissue.

Which brings us back to those tissues sitting on your desk. Companies like Kleenex, Puffs, and Quilted Northern rely primarily on virgin forest fiber — a.k.a., freshly cut trees — to make their product. And that’s just the start of the environmental toll of the tissue creation process. Those felled trees are chopped into chips and then ground into a pulp, a process that requires lots of water to perform. Chemical additives, typically bleach, are then mixed into the resulting fiber to get the soft feeling that your sensitive skin requires.

The thing is, it doesn’t have to be this way. It’s possible to find facial tissue that doesn’t do this type of damage to the planet. According to NRDC’s latest assessment of paper goods, there are some brands that go above and beyond to ensure their products are lower-impact, including Green Forest and Seventh Generation. Somewhat predictably, it’s the big name brands that you’ll want to stay away from: Kimberly-Clark’s Kleenex brand, Procter & Gamble’s Puffs, Georgia-Pacific’s Quilted Northern, and big box stores like Walmart and Costco all manufacture tissues that use primarily virgin fibers.

The best thing that tissue manufacturers can do is simply stop using virgin forest fiber. Recycled fiber will do just fine, with a fraction of the environmental impact. “Tissue made with 100% recycled content has one-third the carbon footprint of tissue made from virgin forest fiber,” explains Vinyard.

Bamboo has also become an increasingly popular alternative. The fiber source occupies considerably less space than forests planted specifically for logging purposes. It doesn’t need to be replanted after being harvested because it grows back quickly, and it doesn’t require planet-harming chemicals found in some fertilizers and pesticides to thrive. Bamboo isn’t perfect, but products made of the plant produce 30% fewer emissions than those made of virgin forest fiber. Vinyard recommends looking for products that carry the Forest Stewardship Council logo, which indicates the brand’s commitment to reducing reliance on forest fibers.

Of course, if you can avoid using tissues at all, that would be even better. Paper accounts for more than one-quarter of all waste found in landfills. While it’s less harmful than other types of waste that can take hundreds of years to decompose, it still contributes to pollution because of the chemicals released in the decomposition process, including the release of wildly harmful methane gas, which is 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide upon its release (though it hangs in the atmosphere for a shorter period).

One retro alternative? Use a handkerchief, which can obviously be reused over and over again while a tissue can only be used once. Handkerchiefs are small, so you can simply toss them in with your laundry any time they need to be washed. While the idea of reusing a cloth that you blow your nose into is gross to some, the fact is that we’ve been tricked into thinking that we need disposable goods to maximize our health. Wash your handkerchief regularly and you will be fine.

If you can’t bring yourself to carry around a hanky, though, then just opt for the lower-impact tissues whenever possible. Remember, we can wield some consumer power here: If corporations notice that your dollars are going toward the more sustainable stuff, they may be more inclined to ditch virgin forest fibers.