Black people don't need Diddy and Ice Cube negotiating for them

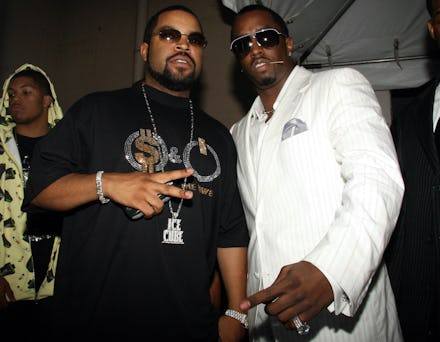

When the internet learned that rapper Ice Cube had worked with President Trump’s re-election campaign, condemnation from “F-ck tha Police” fans — not to mention a broad swath of progressive voters — was swift. Just as swiftly came the biting wit, quick quips, and memes that are Black Twitter’s signature rapid-fire flex. Just a few days later, Sean “Diddy” Combs announced in a series of tweets that he was launching Our Black Party, a new political party ostensibly focused on prioritizing issues and challenges most relevant to Black America. Both rappers created their own list of political priorities — Cube, whose real name is O’Shea Jackson, offered A Contract with Black America, and Combs’s party has released its own agenda — in collaboration with other people they determined were qualified to contribute, including professors, activists, and elected officials.

But these efforts are hard to take seriously. Having transformed their early music careers into sizable wealth and assets, these initiatives feel like rich men attempting political moves they don’t quite have the reach to pull off, instead of, say, collaborating with existing grassroots organizations who are already pursuing these same (if not better) political interventions. Beyond that, both of these proposals damningly reflect a false promise of Black homogeneity, using uncritical calls for political unity to privilege narrow portions of the Black population — while throwing loads of other people under the bus. (Mic reached out to representatives for both Jackson and Combs for comment but did not receive a response before publication.)

To be clear, Jackson and Combs both represent a growing number of exceedingly frustrated Black people. Actually, frustrated is putting it nicely. And as much as the internet might be having a field day with the rappers’ forays into politics, the Democratic Party and the progressive movement at large really can’t afford to dismiss the level of disillusionment that large swaths of the Black American population are feeling right now. After a while, that frustration is going to manifest into something, be it mass uprisings and riots across the country or political interventions like these.

Last week, Jackson hinted at that frustration, in a tweet about the political landscape in the country. “Every side is the Darkside for us here in America,” he wrote. “They’re all the same until something changes for us. ... We can’t afford not to negotiate with whoever is in power or our condition in this country will never change.”

Combs offered a more diplomatic version of the sentiment in an interview with radio host Charlamagne tha God posted on YouTube last week to coincide with his announcement. “It would also be irresponsible of me to just let this moment go by — the world is watching — and not do everything I can to make sure that going forth, that we’re part of the narrative, that we own our politics,” Combs said. He also paired the unveiling of his political party with an endorsement for Democratic candidate Joe Biden.

Jackson’s foray into presidential politics might’ve been a more mundane one if it hadn’t been for his willingness to be associated with the Trump administration — and also maybe if he hadn’t made certain particularly concerning comments in the series of interviews he did after the news broke. In an attempt to both clarify his position and defend himself in a recent CNN interview, Jackson explained, “I’m going to whoever’s in power, and I’m going to speak to them about our problems, specifically. I’m not going there talking about minorities, I’m not going there talking about people of color, or diversity, or none of that stuff. I’m going there for Black Americans — the ones who are the descendants of slaves.”

In an easily dunk-able comment for anyone who has read Audre Lorde, the rapper further explained in an interview with Rolling Stone, “I’m not playing this game no more of jumping on this team and that team and this side and that side. I don’t care. I’m saying I’m a single-issue voter.” As the Black radical feminist and thinker famously declared in her 1982 speech, Learning From the 60s, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives. Malcolm [X] knew this. Martin Luther King Jr. knew this.”

The danger of this line of thinking is that it revalidates and reinvigorates an exceptionally tired position: that cisgendered Black men, those ceaselessly embattled patriarchs, are the de facto public faces, definitive decision-makers, and truest sociopolitical measure of our entire community. It’s this narrative that emboldens Black men to prioritize their needs and experiences — not only over the needs and experiences of women, queer, trans, and nonbinary people, but also far too often at their own expense.

I’m wary of yet another self-proclaimed Black political space that creates an upward climb for anyone who’s not a Black cisgender male.

Jackson’s perspective on building Black wealth and capital demonstrates this quite pointedly to a concerning degree. In the same Rolling Stone interview, he reasoned, “I really only care about [Black Americans] getting capital and equity because we’re not even part of the game. We think we are. We pretend to be. But you’re not even part of the game in a capitalistic society without no money.” He added, “These dignity and social issues definitely need to be handled, but until you have money and capital, you get no dignity in a capitalistic country.”

He's absolutely right. In a capitalist country, the economy only allows for the conditional dignity, personhood, and mobility of people who’ve amassed capital. And in a capitalist economy, that capital is only able to be amassed at the expense of other people. Jackson’s well-intentioned but short-sighted focus on Black American descendants of slavery suggests that he might be willing to accept economic advancements from an entity like the Trump administration, even if it comes at the expense of other vulnerable populations — like undocumented people, Indigenous people, and Black and brown people in other countries that bear the brunt and lasting damage of profitable U.S.-led wars.

The shortcomings of Combs’s political machinations, meanwhile, aren’t as obvious as Jackson’s. The agenda published on Our Black Political Party’s website is actually much more comprehensive and well-thought-out than some skeptics might expect. But as with Jackson, Combs’s interviews offer insight into his thought process — and highlight his blind spots.

For example: When Combs lists the Black activists whose speeches he found particularly inspiring, he names Malcolm X, Martin Luther King Jr., and Stokely Carmichael. It’s a good list; I myself think of this list as the Black male political starter pack. But I can’t help but note a distinct lack of Black radical women activists on Combs’s list, which appears to have a damning lack of intersectionality. Whether that exclusivity bleeds into his political aspirations isn’t clear yet, but I’m wary of yet another self-proclaimed Black political space that creates an upward climb for anyone who’s not a Black cisgender male.

In conversation with Charlamagne tha God, a.k.a. Lenard McKelvey, Combs explains what might be understood as the thesis of his new political party. “Our Black Party’s number one goal is to unify behind a Black agenda. That’s it,” he says matter-of-factly. “You can be a part of the Democratic Party, the Republican Party, you can be an independent — but if you Black, you wasn’t born Republican. You wasn’t born Democrat. You wasn’t born independent. You was born Black.”

At best, this perspective again misrepresents Black people as a monolith who have the same vulnerabilities, the same political priorities, and the same critical understanding of either of those things. At worst, it hints at racial essentialism. As much as the warping of identity politics might suggest that the existence of an identity is a suitable stand-in for an entire set of political views, that just isn’t true. And that presumption is in large part why identity representation remains an understandable emotionally powerful, but materially insufficient goal.

There’s also the fact that Combs chose McKelvey of all people to help debut Our Black Party. McKelvey has a track record of making flippant comments about sexual assault and pedophilia, has dealt with sexual assault allegations made against him, and once said on air that he might’ve assaulted his wife the first time they had sex. McKelvey’s wife has since publicly stated that she was conscious during the interaction and doesn’t consider it assault, but her husband’s seeming inability to treat other people’s vulnerabilities with dignity and respect makes him a questionable figure for Combs to involve in the launch of his political effort. It’s difficult to imagine that the pair of them would go out of their way to cultivate a political climate that ensured each and every individual in that space felt empowered.

Combs also discussed with McKelvey the significance of local elections as he understands it. “When we get down to the local election, when we get down to the school board, when we get down to the judges and the justices — that’s so confusing for us,” he said. “We’ve never played this game. It’s another level of gangsta. But I’ve played this game before, you know? I started in 2004 with Vote or Die and this is the evolution of that thought, of that empowerment, of that independence.”

I certainly commend Combs for having built his own experience in the electoral political sphere, but if 2004 is the beginning of your Black electoral justice framework, you’re missing out on decades upon decades of strategy, insights, and experience. Iconic giants of Black activist history like Fannie Lou Hamer and Ella Baker, alongside massively impressive voter registration efforts from grassroots groups like the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) and the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), are crucial to understanding the legacy of Black political action. Combs seems to be missing all of it.

To be clear, none of this is about “staying in your lane.” Black musicians and other artists have a long history of being deeply involved in political movements in a range of ways, from creating music and content to providing political commentary or getting involved in grassroots organizing efforts and advocating for legislation. But blind spots are blind spots. And when it’s so easy for rich, famous men to command attention for anything they do, it’s especially critical that we call them out with clarity and precision to keep the most vulnerable among us safe.