Scientists are trying to make the first-ever master list of every species on Earth

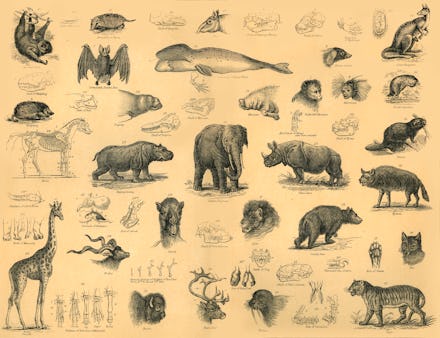

A team of researchers is urging the scientific community to create a universal species list that could make it easier for conservationists to prevent biodiversity loss and keep researchers on the same page about species and animal taxonomy. In a report published on July 7 in the journal PLOS Biology, the authors describe the current situation as one fraught with disagreement as researchers, conservation groups, and governments make difficult decisions about what constitutes a species. No one has ever reached a single standard for all species, which is why there are so many differing lists for mammals, insects, plants and other creatures.

The CITES and IUCN lists are two examples of this problem, noted Professor Frank Zachos, co-author of the report, to The Guardian. CITES focuses on species that are threatened by international trade, while the IUCN focuses more on the conservation status of species. So the IUCN may mark a species as threatened due to habitat destruction, but CITES might not have it because it isn't threatened due to international trade. In a case like this, a conservation group using one list but not the other might miss an opportunity to help a critically threatened species.

"So, in theory," Professor Zachos explained, "you can look up a species in [CITES] then go the [IUCN list] and you will not find this species, or you will find something that has the same name but actually is not exactly the same as the [CITES] list."

This can make cooperation between groups or government entities difficult. Without a universal species list, wrote the authors, experts and environmentalists face four major problems: Some people won't realize certain species exist due to a lack of access to studies or other literature; current data about the classification of species is scattered, which makes it harder for scientists to find and improve; multiple species lists can be confusing for users who might not understand the difference between them; and people using outdated lists might not realize they're outdated.

A universal list would solve all these problems. All the data would be gathered and updated in one place, and users would only have to look up one list for an accurate reference. Everyone would benefit, stated the authors, including taxonomists and the commercial sector.

But creating a universal list isn't easy, the team acknowledged, as determining what's a species and what isn't can be a matter of opinion. Using African elephants as an example, The Guardian pointed to research that provided evidence suggesting that the species could be split into two types: Forest and savanna elephants. However, the African elephant is listed as a single species by both CITES and the IUCN, which can affect conservation efforts for each type.

Furthermore, there's evidence that some species are still going through an evolutionary process.

"For probably 90 percent of the species, there are natural units, they don't interbreed and they're well behaved," lead author Stephen Garnett told The Guardian. "But there's 10 percent that are busy evolving and we have to make this decision about what is the species and is not."

To make it easier, and more appealing, to make a universal list, the authors of the PLOS Biology report suggested 10 standards any collaborators should follow to make it as transparent, accessible, and accurate as possible.

The researchers believe the species list has to be based on science without any "non-taxonomic considerations and interference" such as economic or political influence. The creation of the list has to remain collaborative and balanced, letting contributors' voices be heard if they have a concern, and to encourage continued academic research and progress in taxonomy.

"The easiest response to a lack of power is to refuse to participate," warned the authors, so "there needs to be active engagement by a wide range of potential users if a unified global list is to be globally supported."

That means the creation of the list has to be transparent, too. It's no secret that there are arguments and debates among the scientific community about the classification of some species, so differences in opinion among experts must be discussed and worked out. If edits are made to the database, there should be a record of who did it — a process not unlike how Wikipedia or Wikispecies works.

Transparency also includes transparent and consistent rules used to recognize species, crediting researchers and authors, citations to authoritative sources, and keeping an archive of older versions of the list.

Creating a universal species list is an endeavor that could take years. Yet the authors believe the effort would be worth it, and that now is a good time to try. With advancements in technology making it easier to spread and access info, they think creating this foundation for a global list will encourage participants from all over the world to contribute to what we know about the Earth’s biodiversity.