Can loneliness lead to unemployment?

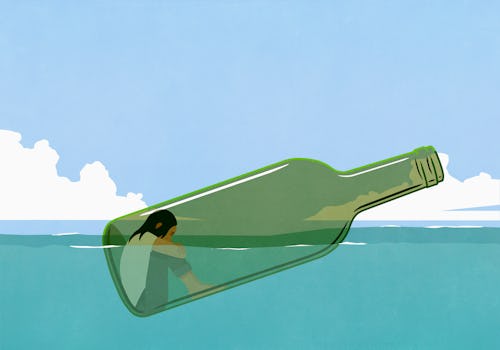

A new bummer of a study suggests that people who are lonely are more likely to lose their jobs.

The loneliness epidemic that experts have been warning us about for years has been magnified by the COVID pandemic. Almost 40% of Americans say they feel “serious loneliness” and while feeling lonely isn’t classified as a disease, loneliness negatively impacts health and can exacerbate mental health issues. Not only that, but a new study suggests that people who are experiencing loneliness are at a greater risk of unemployment.

The study, which was published yesterday in the journal BMC Public Health, analyzed data from 15,000 people in the U.K. for three years spanning 2017-2020. What researchers found was that people who were defined as lonely near the beginning of the study were 17.5% more likely to become unemployed by the end of the study. It’s important to note that most of the research for the study was conducted before the pandemic, so we don’t know exactly how these numbers might look now.

That increase feels staggering to me, but it confirms other recent research into the connection between loneliness and unemployment, globally. Past research, however, generally focused on establishing that unemployment leads to loneliness. This research is the first to point out that the relationship between loneliness and unemployment works in both directions. “Our findings show that these two issues can interact and create a self-fulfilling, negative cycle,” Ruben Mujica-Mota, associate professor of health economics in the University of Leeds’ School of Medicine and co-author on the study, told The Independent.

Why might loneliness be so intimately connected with unemployment? Well, the truth is that there are a lot of social, cultural, and cultural variables that play into both. “One possibility is that people who suffer from loneliness have developed beliefs that they are unwanted, or ‘outsiders,’ which makes it a lot harder to work with others, and could be connected to depression or social anxiety,” says Aimee Daramus, a Chicago-based psychotherapist. These connections between mindset, mental health, and loneliness could be part of the “self-fulfilling, negative cycle” that the researchers who wrote the study were trying to get at.

Other experts I spoke with for this article agree that the symptoms of loneliness can lead to a state of mind that makes having a job more difficult, and vice versa. But it’s crucial to point out that these symptoms are not “all in someone’s head” — loneliness can lead to physical pain that is a hindrance to employment. “Like depression, loneliness can feel physically painful,” says Stefani Goerlich, a psychotherapist in Detroit. “This results in a cycle of self-fulfilling inertia, where the lonely person doesn’t feel up to the effort of seeking community — such as work — which reinforces their isolation. It feels physically too difficult,” Goerlich explains.

It’s crucial to point out that these symptoms are not “all in someone’s head.”

There also could be cultural forces at play, says Daramus. This research was done in the U.K., which has substantially more humane employment laws and norms, so the reality is that it could be different in the U.S.. “The US has a much stricter sense of what work is than a lot of other countries, where vacations and prioritizing family are more accepted,” says Daramus. Ugh. If Brits who have much more stable employment than people in the U.S. are struggling with loneliness and unemployment, what hope is there for us?

Obviously no one can predict how this same study would play out here, but my guess is that ‘Murica’s so-called work ethic might not exactly boost our sense of connectedness. Yes, says Daramus, “If working means not seeing your family and friends often, that could be a factor.” Personally, I’d like to live in a world — or at least a country — where we don’t have to choose loneliness or unemployment, but the research on that world isn’t yet peer reviewed.