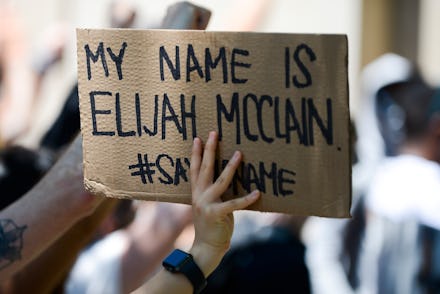

Elijah McClain and the pitfalls of the "perfect victim" narrative

Like many, I was gutted when I learned of Elijah McClain’s death at the hands of Aurora, Colorado police last August — the disturbing details of which have resurfaced in recent weeks. I identified with his quiet quirkiness, which made it easy to imagine him as someone I could’ve been friends with, had I known him. At the same time, I bristled at the flood of social media posts emphasizing how McClain was a vegetarian, played the violin for kittens, and had other “redeeming” qualities that made him the “perfect victim.” “This one hurt,” some said.

Yet the deaths of George Floyd, Tony McDade, Breonna Taylor, Sean Monterrosa, Andres Guardado, and so many others due to police violence should all hurt. Neither McClain, nor any of the Black and brown people killed by police, need to be perfect victims to deserve our grief.

Fixating on how the innocence of a victim of police violence made them undeserving of their death implies that those who had less-than-spotless pasts did deserve their fate. By the same token, the victims' loved ones and others demanding justice for them shouldn’t have to prove that they didn't deserve to be killed by police — which only highlights that their lives were devalued to begin with. Whether they were “good” or “bad” is beside the point: None of them deserved to die of police violence because they were human beings, period.

We need to be careful with perfect victim narratives, as well-intentioned as they might be, because they can reinforce white supremacy. They’re rooted in the racist notion that “those of us who come from marginalized communities have to earn that right to be valued, that we are not born inherently valued,” says Alfiee Breland-Noble, psychologist, professor, and founder of The AAKOMA Project, a mental health nonprofit with a focus on the experiences of youth of color. “This idea of the perfect victim has to do with who is worthy of our empathy or sympathy, and who’s not.”

The perfect victim narrative essentially creates a hierarchy of victims whose lives had more value than those of others, explains Shardé Davis, an assistant professor of communication at the University of Connecticut. Conversations and media coverage might focus on, say, how they were highly educated, played a musical instrument, volunteered, or had other qualities that a society built on whiteness considers valuable. “The qualities we pull out are rarely qualities that we traditionally align with Black traits,” Breland-Noble tells me. “There are no singularly Black traits — those don’t exist — but if you look on a continuum, there are things we traditionally associate with Black people and things we traditionally associate with white people.”

McClain absolutely deserves the outpouring of support he’s received, but I can’t help but wonder whether much of it has do with Black male respectability politics. His mild manner, clean-cut appearance, and love of the violin make him palatable to white people, and therefore, the rest of us who inhabit a society that puts whiteness on a pedestal. Again, just because he felt approachable and familiar to me and others doesn’t mean his life was worth more than the other Black and brown lives stolen by police.

McClain’s family attorney, Mari Newman, has said as much. “Every Black life that is snuffed out by law enforcement certainly deserves the same degree of attention and the same degree of outrage,” she told CBC Radio. “It doesn't require a person to be perfect. And, in fact, when the analysis turns to how good a person the victim was, we're looking in the wrong direction."

Public opinion of the victims killed by police more or less follows the same pattern. Soon after initial reports of the tragedy, “most of the time, if not all of the time, people start looking for reasons to excuse the behavior of police officers,” says Nia Wilson, co-director of SpiritHouse, a group led by Black women that advocates for the abolition of police and prisons, grassroots leadership, and more. Suddenly, the victim’s criminal record and other “dirt” from the past starts to turn up, “in order to somehow place blame for a person’s death on themselves”

We saw this with Michael Brown, when the New York Times wrote he “was no angel,” having stolen cigars and pushed a convenience store clerk. Trayvon Martin was suspended from school for having weed on him. Jeronimo Yanez, the police offer who killed Philando Castile, said the odor of weed in Castile’s car and the gun he had on him — even if he had a permit to carry it — terrified him. George Floyd had been incarcerated, and had methamphetamine and fentanyl in his system when police killed him. Tony McDade and Erik Salgado had also spent time behind bars.

As Davis points out, such details are distractions — they have zero relevance to these victims’ murders by police. They merely comfort those who want to believe that police are good, and anyone harmed by them must have done something in their lifetime to warrant it, Wilson tells me. Those who subscribe to this narrative aren’t subject to police violence themselves and “consider themselves good people,” she says. “It helps them feel less concerned that anything like this could happen to them,” making it easier for them to dismiss the tragedy and move on with their lives.

What’s more, isolating McClain as a “good” victim enables them to brush him off as an exception to the rule that police brutalize only “bad” people, rather than acknowledge the reality: that they systematically target Black and brown people, regardless of whether they’re “good” or “bad,” Breland-Noble says. “If I can tell myself that the Elijah McClains of the world are aberrations, I can still feel comfortable with my current worldview.”

In this way, white people can continue believing in the goodness of a system that’s never been good for BIPOC, absolved of the responsibility of examining it and how they benefit from it. For many, shattering this illusion to reveal a system that requires constant risk analysis to navigate — especially for Black people, whose very lives depend on it — “is heavy,” Breland-Noble says. “That can break people apart, and then they feel helpless.”

Indeed, white people would need to accept that they don’t face the same pressure as Black and brown people to prove their innocence or exceptionality. We see this in their frequent depiction as victims of the very qualities used to legitimize police violence against Black and brown community members. “Someone who has a mental illness or a drug addiction is seen as someone who was unable to get the treatment he deserved,” Wilson points out. These qualities are even used to lessen their culpability for violence they themselves committed, as seen in portrayals of Dylan Roof, Stephen Paddock, and other white mass murderers as mentally ill.

That said, while we don’t want to fall for the myth that, of all people, McClain didn’t deserve to die, “it is important to highlight the humanity of an individual,” Davis notes. We’ve seen this in coverage of Breonna Taylor as an EMT with dreams of becoming a nurse, and of George Floyd mentoring youth and holding his daughter, Gianna “I think that’s important, to show that he was a person, especially for Black men, who are dehumanized.”

Still, that the Black lives stolen by police violence need to be validated, protested for, and called into question again and again “is a clear example of racism,” she says, one that communicates that Black bodies are inferior and subordinate to white bodies, once codified into law with slavery. Likewise, the three-fifths clause, though no longer law, still plays out in how police and society more broadly treat Black people as less than human, and therefore, less worthy of life, Wilson says. It's a reminder that this country was built to secure the safety of white people, and white people only. “The police are not here to keep us safe,” she says. “They’re to keep white people safe from us.”

Expecting those fighting for justice for Black and brown victims of police violence to prove they were innocent, perfect victims also reinforces the all-too familiar message that their lives had no value unless others, namely white people, say so, Breland-Noble says. In reality, they don’t owe anyone an explanation for why their lives mattered — they’re the ones owed an explanation for why those who had sworn to "protect and serve" murdered their loved ones.

“I hope we don’t injure people more by requiring that they justify why that loved one was valuable,” Breland-Noble says. “We’re valuable because we’re human, and we exist.”