Hari Ziyad on cultivating a world where Black queer people can thrive

A big part of creating a world where Black queer people can thrive involves facilitating change where it's needed most urgently. This can mean addressing trauma both within your own social circle as well as battling harms caused by elected dumpster-hearted swamp donkeys for whom your thriving is not a priority. Truly though, the most world-shifting work can often start within.

As proven time and time again by my Inner Hater’s crushing self-criticism, oppression doesn’t only happen out in the world. I personally fight a daily battle to figure out how to love my occasionally ashy, Black, gay-ass self and others despite being programmed otherwise. Liberation comes in many forms.

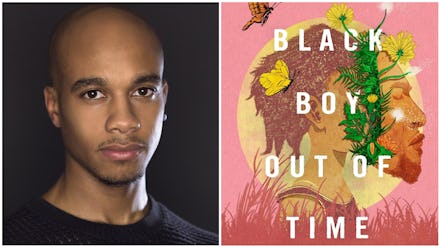

I recently connected with journalist, prison abolitionist, editor-in-chief of Racebaitr, and author Hari Ziyad to discuss this very inquiry — what it means to reconnect with your inner child and unpack the psychological and interpersonal impacts of growing up Black, queer, and non-binary in this violently anti-Black, anti-queer, ableist, carceral society. In their new memoir that dropped on March 1st, Black Boy Out of Time, Ziyad, raised by a Hindu Hare Kṛṣṇa mother and a Muslim father in Cleveland, Ohio, writes through their upbringing and journey of self-acceptance and reckoning with the insidious influence of binary, prison-based world views.

We talked about finding solace amidst grief, working to recognize when we’re too hard on ourselves because of negative messages we’ve internalized, and their unique approach to provoke change in both their village and the system at large.

Alex Hardy: In your book, you describe “finding what about you is worth saving in an anti-Black, anti-queer world.” When did you first become aware of the concept?

Hari Ziyad: I don’t know that there is one singular moment. It was more like a series of events. Looking back, I could see where things shifted in the way that I moved about the world and the way I was starting to shape my ideas around myself. One was when I got my first haircut on my fifth birthday. This was the first time gender was part of my life in a way that was tangible. This was me changing my actual body to conform to this idea of gender. That is a moment that preceded a lot of gendered messages that my parents, in particular, began to more explicitly relay to me. That was a pivotal moment.

There were also experiences of sexual violence that really encapsulated the changes in perspective in how I viewed myself, what I was worthy of, and what I needed to do to protect myself. After those experiences, a lot of those boundaries and shields that I thought were just between me and the rest of the world — but were also between me and parts of myself — began to be erected.

From very early on, children start to hear those messages. I was lucky, in a lot of respects, because of the way my parents raised me. My mother homeschooled us. She was very intentional about shielding us from receiving all kinds of messages from the world. She had her reasons for that, but I think I gained a tool that I was able to later use from that when I started to recognize that the messages I received about myself and my queerness were being weaponized against me, too.

AH: You weave throughout the book a series of letters to your Inner Child. Now that you are on this journey of unearthing and re-engaging, how is that inner child responding as you engage in these conversations?

HZ: I’m still definitely on this journey. I’m able to conceive of my anxiety a lot within the lens of my Inner Child and what they might be trying to say to me. It comes up a lot around my work and thoughts around how what I’m doing that might not be good enough. I'm able to see now that’s rooted in not being there for them and paying attention to their fears, which are very valid.

I’m able to slow down and tend to myself and rest more. That’s the biggest thing, especially during the pandemic: rest. That’s the overarching thing that my Inner Child has been telling me — to slow down, but also to do my altar work and do the things I know are going to ground me when I need grounding.

AH: You also write through the idea of engaging by questioning and resolving the “shame-based limiting beliefs that prevent us from loving ourselves.” Do you feel there has been any resolution in these conversations?

HZ: I wonder if I would still use “resolve” again, at this point. Because even the resolution is still a process. But so much of my relationship with my mother in particular, the harms that we had to work through before she passed, feels a lot more resolved now. I heard someone speaking about grief recently, and they said they didn’t believe in closure and that it’s not a thing.

We were able to move into a new stage that felt like we were in the process of healing, which I guess is as close to resolution as we can get. One you’re on that train, hopefully you can keep going and it’ll keep feeling better even if it’s never completely done. And that’s where I feel like we were able to leave things, because of that work.

AH: What are some ways LGBTQ folx — who’ve been dealt all kinds of fucked up blows by this violent, capitalistic system — can create our own systems of support, care, and accountability?

HZ: That’s a really great question. The thing I think is most important about doing that work is recognizing how it shows up in us and how we treat ourselves. Yes, ultimately, we want to be able to do that shifting within our families and larger communities and with the world.

That’s what brings about abolition. But we also have these punitive views towards ourselves, and that shows up in the self-talk that we have, and when we don’t feel good enough, when we don’t listen to the very clear warning signs that tell us not to do something because we don’t trust ourselves, because we don’t have a loving relationship with that part of ourselves.

It’s really important, particularly for queer people, because we’ve been so conditioned to internalize a lot of really negative things about ourselves. And to be really intentional about naming the ways that we are punitive with ourselves and to work on those things every single day. This is why therapy is so important for us, even though, and you know this, it’s hard to find a good therapist to help you do that work. But once you do, that’s really critical, at least for me, and has been a huge part of how I’ve been able to get a better relationship with my queerness and the things that I’d associated with that.

AH: What role does joy play in your work?

HZ: Joy is critical. Having joy is why I wrote the book. I realized that I used to experience the world in a way where I was joyous. And on this journey to reclaim that, you gotta dig through a lot of shit that’s not always going to feel joyous to dig through, but the purpose of doing all of that was to get back to that place. I think I am much closer to feeling that kind of joy, which is not necessarily the same as happiness and maybe that’s why the book feels so heavy, because it’s not a “happy” book.

But it is a book that I hope, once you get through, you’ll be able to connect with the joy. Because when I finished writing it, I felt much lighter and much more capable of accessing joy, more capable of being able to recognize when joy shows up.

I think now that I have more of a sense of what joy actually is. There were times over the past few years where there was joy around me but I couldn’t even tap into it or access it because I didn’t even know what it was. That’s because I was so disconnected from it that when I saw joy, my instinct was to push it away, start to doubt it, be suspicious of it. This book is me unlearning that process.

When I see joy now, I can just let it sit. That shows up in a very tangible way, in what I’m willing to criticize. You’ve known me for a long time. I criticize lots of things, all the time, and I’m not saying that’s a bad or a good thing. One of the things it did was that it didn’t give me time or space to recognize joy when it showed up. I hope that you’ve seen a shift in me.

AH: Have you seen any shifts in yourself in terms of how you show up for others — as an abolitionist, as a son, as a partner, as a community member — because of this work?

HZ: Yeah, definitely. I don’t think I would have been able to get through what was required while my mother was passing without doing this. There was just so much stuff that was getting in the way of what was necessary, which was for all of us to be there and for me, what was necessary was to communicate how much she meant despite all of this, while holding her accountable for everything that happened. I wouldn’t have been able to do that without the work that I’d done.

I realized, by the time my mother did pass, that through the conversations that we had, it was very clear — more clear than it had ever been — that there was a deep love at the root of all of it. I lived with my family for the last six months of my mother’s life. And we took care of her and I Ieft my job, and we are, as a family, much closer. That’s all part of the work that I did with the book, and that my family was all doing together.

And I think, in general, I’m showing up more hopeful about what’s possible. I think I always viewed the world as like, it’s possible to change but it’s probably never going to. And I feel to an extent there’s probably a limit to the shifts that can happen on a bigger scale. But as for the things that are happening in my life and in my relationship, and in my community that I can do and shift around to make the world a less carceral place, there’s so much more possibility there.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.