"Tweeting for oxygen and dying": Young people in India are turning to social media to save lives

Most nights during the past couple of weeks, I’ve woken up twice. Once, to listen for discomfort from the neighboring room where my COVID-positive septuagenarian parents are asleep. The second time, to physically walk over with the black-and-white, life-affirming pulse oximeter at the ready — should I need to administer the little help I can offer. This would mean clasping the tip of their finger in the folds of the oximeter, in a bid to tell if their blood is appropriately saturated with oxygen — oxygen which hospitals have run entirely out of.

The terror I don't dare vocalize is this: What do I actually do if the number is lower than it should be, in the India of right now?

This reality is grim. New Delhi (where I am) and the rest of India is facing a horrific second wave of the pandemic that has ratcheted up the body count in a few weeks, with people dropping like flies inside hospitals, outside in parking lots, on the streets, and within their own homes, due to a critical lack of oxygen. As of May 4, India has recorded 20 million COVID cases — which is a little over one-seventh of the total number of cases worldwide (154 million).

In the last 24 hours alone, it has recorded 368,147 new cases — a number that experts widely claim to be underreported. On April 15, for example, the city of Bhopal officially reported four deaths from COVID-19; yet the Hindi-language daily Dainik Bhaskar found 112 COVID funerals to have been conducted in three crematoriums across the city. On April 12, the city of Ahmedabad reported 20 COVID-19 deaths; the daily Sandesh found 63 at just one hospital. And a New York Times investigation, over a fortnight in mid-April, found more than 1,000 COVID-fueled funerals in Bhopal’s crematoriums and burial grounds, even as the city officially reported that only 41 people had died from the virus.

How can I paint a picture of our crisis that will appropriately encapsulate the colossal loss and palpable terror that govern us right now? Perhaps the glowing funeral pyres of our loved ones’ bodies in plastic bags, queued one after the other to be consecrated to ashes, will tell their story.

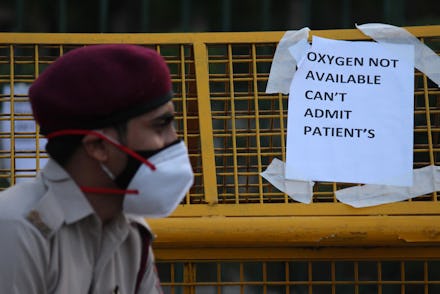

Or maybe I could point you to Twitter and Facebook, where hospitals have been sending out an SOS for oxygen, asking ordinary citizens to “amplify” their tweets and hoping someone in power will listen. I could also show you a video of the doctor at Jaipur Golden Hospital who, last week, broke down on camera while recounting the deaths of 20 COVID-19 patients due to lack of oxygen — or to the fact that 12 more died for the same reason at Batra Hospital in Delhi last Saturday. COVID-19 has been preying silently on India's villages, as people fall to breathlessness that was never diagnosed.

I could also point you to the traumatic Twitter thread of a senior journalist in Lucknow who live-tweeted his own depleting levels of O2, with a photo of his index finger pinched by a pulse oximeter. “My oxygen is 31 when some (sic) will help me”. No one did. The journalist’s son confirmed his death — 20 hours after his father first tweeted, asking the government for help.

In the last three weeks alone, I have lost an aunt and a former school teacher and witnessed two 30-year-old colleagues seek emergency ICU care. Friends have lost family, family members have lost friends — the list, when you scroll through Indian Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram, is endless.

Criticism has mounted over the government’s go-ahead to cancel superspreader events like the Kumbh Mela (a mostly outdoor Hindu religious gathering where millions take a dip in the River Ganga — daily COVID cases rose by over 450% between April 1, when the Mela began, and April 17, when it was finally called off) and election campaigns in five Indian states, where politicians across the spectrum roamed unmasked.

“If people like you and me can do it so easily, imagine how much the government can do”

So, what now? In the absence of a unified address from the government and any public signs of reassurance, where does one turn? For the citizen with a smartphone, social media is the first and last resort — a symposium of hope and hopelessness, shared at once with a bevy of empathetic strangers.

Twenty-eight-year-old Tanu Dogra, who lives in Delhi, realized she needed to help after witnessing firsthand the crisis of depleting resources during her own recovery and her uncle’s hospitalization with the virus. “My uncle is in his 50s with comorbidities and his oxygen began to dip 10 days ago,” she says. His levels had fallen to the 70s (a healthy person’s oxygen saturation is usually between 94-100%, and anything below 90 is alarming) when she found a place for him in a hospital.

Dogra recalls the “longest night of her life” when, even as her uncle was stabilized with oxygen, she watched CPR performed twice right in front of her. “I watched two patients die minutes apart in the general ward and it broke me,” she says. “I stood holding the curtains around my uncle’s bed to ensure he didn’t see anything — and later, held the families of the dead as the overwhelmed staff ran around.”

Dogra quickly realized that what she saw online was only a fraction of the pain and the reality on the ground — and that she wanted to help. “I came across people asking for resources online and started amplifying them on Twitter and Instagram, tagging the social media accounts of journalists, Delhi Govt. volunteers, their health team, and my friends, to widen reach,” she says. "I call this bunch ‘necessary samaritans. It’s also the name of our group of friends on Whatsapp whose raison d’être is to consolidate leads, try to verify them, and share it with people or chase them ourselves..” Most of these leads involve hunting down oxygen cylinders; hospitals with available ICU beds and ventilators; and drugs such as Remdesivir and Fabiflu, which are sometimes prescribed to help treat COVID-19.

Amrita Karmakar, 33, who lives in Mumbai, another Indian metropolis hit hard by India’s second wave, follows a similar modus operandi. Karmakar has joined a task force of online volunteers who connect “resources” to the people who need them. “Sometimes all I do is a simple Twitter search where I type in something like ‘city name, blood/plasma/hospital required’ and then the tweets of people or places that can help pop up in my feed,” she says. “Yesterday, I connected four people like that — in Agra, Mumbai, Kolkata, and Bangalore. If people like you and me can do it so easily, imagine how much the government can do! What was so hard? They could have made an address to the people, anything.”

Kolkata-based Malini Chakrabarty, 23, has actively taken to social media (and beyond) to recounts initially trying the state of West Bengal’s Swasthya Bhawan Emergency helpline whenever her friends needed medical help. “Unfortunately, it would almost always be busy and we’d turn to social media,” she says. “Soon, we realized that most of the public were facing this crisis, and we started verifying numbers and updating a Google spreadsheet with COVID resources — such as hospital beds, plasma, oxygen, food, etc. We work in shifts and while one team is verifying leads, another updates the spreadsheet.”

"If people like you and me can do it so easily, imagine how much the government can do! What was so hard? They could have made an address to the people, anything.”

Chakrabarty says she has also been taking SOS calls for doctor consultations, animal health emergencies, and food and medicine delivery. While she’s trying to stay home most times, she has to get on her bicycle for deliveries and to feed stray dogs in her locality. “They're depending on me and I have to deliver.”

Karmakar tells me help can appear today in the form of magnanimous teenagers on social media, and she’s not far off. Dumdum-based Ishani Routh is only 19, and she’s been working relentlessly to ease information access on every platform. “At first, I jotted down all the contacts of oxygen leads of various areas of our state and tried to circulate them,” she says. “Strangers came forward to help — sharing the information on their pages — which helped it reach a large number of people. Then, I built a network of friends and acquaintances through whom I could get information about bed availability in various hospitals and medical facilities. I share this information constantly — and if I see someone appealing for help, I reach out.”

“Thanks for trying everyone, but my friend has passed away”

Still, Indian Twitter represents only a fraction of a populace — those with a modicum of privilege who can access social media. As Karmakar mentions, “the most heartbreaking thing is that most people who need help aren’t tech-savvy.” Yet, it’s telling that even those who are have no access to the limited supply of resources. A dizzying series of “urgent appeals for a ventilator” is usually punctuated by one sepulchral tweet: “thanks for trying everyone, but my friend has passed away.”

The pace at which death comes is unprecedented — and ironically, deadening. “Even as we speak, I am trying to find an ICU bed for a 55-year-old lady in Bangalore. It’s already been 48 hours and just because her oxygen level is not below 85 yet, her ‘number’ hasn’t come," Karmakar says. "The doctor has clearly told her that her oxygen is falling; despite consuming a huge quantity of oxygen through a cylinder at home, her levels are not stabilizing." She needs an ICU — yet, she is just not ‘serious’ enough, she says. It's come to the stage where volunteers, hospitals, doctors are being forced to ‘choose.’ Which case is more critical, and who deserves to be saved first.

Chakrabarty shares similar harrowing accounts of loss and chaos. “Last night, a 10-day-old baby needed oxygen and none of my leads could supply an oxygen cylinder — they could only offer refills for existing cylinders,” she says. “The child passed away and I’ve been sleepless until now, thinking of how all she needed was oxygen.” She wishes those trying to help didn’t have to contend with people hoarding O2 cylinders.

The problem of abject lack and human apathy is one that Delhi-based Abu Sufiyan, 28, has also been witnessing. “The black marketing of oxygen concentrators, cylinders, flow meters, and medicines like Remdesivir, Fabiflu et al during this time has worsened the situation,” Sufiyan says. “While a vial is available for a few thousand rupees (approximately 27 U.S. dollars), it is often being sold to people for 50-60,000 (over 800 U.S. dollars). Even though there is no guarantee that the medicine will save the patient, people are becoming puppets just to save their family members.”

Sufiyan started a crowdfunding campaign on the platform Milaap that aims to supply oxygen support and refilling, oxygen concentrators, ambulances, and even educational support to children who have lost their parents to the virus. He has already raised Rs 41 lakh (55,575 U.S. dollars) in six days and says he hopes to reach at least 3-4 crore (542,190 U.S. dollars) over the month.

Strangers are becoming “saviors for millions”

Sufiyan claims that this people’s alacrity to help is the only “system” he sees working right now. “Total strangers have come forward to help one another — from procuring oxygen cylinders for others out of their own pockets to standing in long queues to refill an empty one for a stranger in need…it is people who are channeling resources on the ground and doing what the government is supposed to be doing,” he says. “In the light of complete governmental failure, social media is a saviour for millions.”

Chakrabarty reiterates: “It’s not that the government doesn’t have resources; it has been showing that it doesn’t care about our welfare. A 20,000-crore Central Vista project was greenlit as an ‘essential service’ in these times — even as people are tweeting for oxygen and dying.” The Central Vista project is a pet project of the Narendra Modi government that aims to tear down and rebuild several old buildings and iconic landmarks, while also building a new Parliament. It has received immense flack in the past year for continuing amidst the pandemic.

“I think it’s very important to realize that we are not dying because of the virus, we are dying because of the government’s ill-preparedness to deal with it,” Dogra says. She has lost a majority of the patients she has attempted to save and she attributes the loss to the lack of adequate and timely medical support.

Most of the good Samaritans of the online world I speak to report running on fumes; in the face of a stranger’s constantly plummeting 02 level, they see-saw between hope and despair — hope, solely because the next stranger is as kind as themselves.

“It’s equal parts inspiring and disturbing. Inspiring because it pushes one to keep at it — this is the first time I’ve witnessed such a spectacular display of citizenry. Disturbing because the government’s job is being done by the citizens, accountability where accountability lies doesn’t seem to be the norm anymore,” Dogra says. She’s also working to understand how she can better help the destitute who do not have access to social media and collaborating to build such channels.

On April 28, the #ResignModi hashtag calling for Prime Minister Modi’s resignation was briefly blocked on Facebook, leading to swift backlash from Indian and international users of the Mark Zuckerberg-led social networking site. The hashtag became accessible again after a few hours, with a Facebook spokesperson saying: “We temporarily blocked this hashtag by mistake, not because the Indian government asked us to, and have since restored it.”

Nothing about the last month in India has been a mistake. Not the talons of global capitalism that've cut into certain demographics, not the willful ignorance of leadership, and not the exceptional efforts of young citizens leading movements to help and heal. Hopefully, none of these lessons and lives are lost in vain.