Nadya Okamoto doesn’t care how gross you think her TikToks are

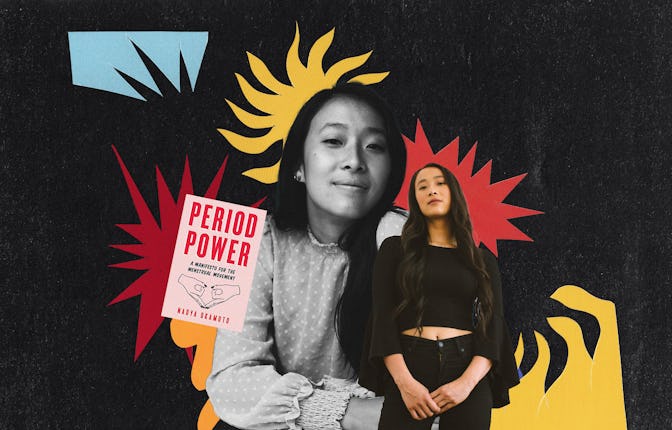

The 24-year-old behind August, a brand redefining periods, talks about handling controversy, ditching euphemisms, and spending lots of time making content in the bathroom.

I vividly remember stuffing a pad in between my button-down shirt and my school skirt in junior high. I was on my period, and my uniform didn’t have pockets, so the tight, conspicuous space inside the waistline of my skirt seemed like the only viable solution. I felt stressed and embarrassed whenever I’d excuse myself to go to the bathroom — “what if it falls out?” and, “what if everyone sees?” were top-of-mind thoughts. But that’s how it was back then, at that age. Girls didn’t discuss poop concerns. And they definitely steered clear of period talk.

In the 20 years since then, change has been minimal — but Nadya Okamoto is on a mission to shake things up. Her sustainable period-care company, August, prioritizes period education with its euphemism-free messaging and raw, vibrant images, as well as its collection of tampons, pads, and liners — the latter of which boast plastic-free, dissolvable wrappers. The brand’s goal: demolish stigmas around menstruation, while providing period products that are better for people who have periods and for the environment.

At 24, Okamoto is young by entrepreneurial standards — but in reality, she’s already lived several lives. When she was 16, she founded Period, a nonprofit committed to ending period poverty; at 19, she became the youngest Asian American to run for city council in Massachusetts; at 20, she published her book, Period Power: A Manifesto for the Menstrual Movement; and at 21, she launched August (named not for the month, but for the word’s dictionary definition: “majestic dignity”). Impressive, yes — but Okamoto’s journey hasn’t been without roadblocks, struggles, and stumbles. When she was in high school, she and her family were “legally homeless,” relying on friends for temporary housing; during her Period reign, peers accused her of taking credit for other people’s — namely Black and Brown activists — work; and her grandparents disowned her after she launched August. Throw in an identity crisis that saw Okamoto grappling with her heritage, and you have a pretty complex, storied road to entrepreneurship that all unfolded before the Harvard College graduate reached her mid-20s.

Three years after August’s launch — and $1 million of revenue later — I spoke with Okamoto about growing through controversy, reconnecting with her heritage, and making content in the bathroom for her 4 million TikTok followers.

You have such an open-minded approach to period care. Has that always been the case?

I definitely think that a lot of how open I am with periods evolved from growing up in a household with a single mom and two younger sisters. It was four girls to one bathroom. There was no aspect of hiding. There was no aspect of being nervous that a non-menstruator or cis-dude in the house was there to see it. Everything was very open. A lot of the way I think about periods or even the way I envision what period positivity looks like originates from that setting. I was still very much affected by period stigmas and feeling nervous and being teased by middle school boys. It definitely has been a journey, but I very much attribute a lot of the way that I am period-positive and how I lean into that to my upbringing.

“If anybody ever wonders if period stigma exists, they should just look through the comments on some of my period blood videos.” - Nadya Okamoto

A lot of the images used in August marketing are ones I didn’t see growing up — like ditching the blue liquid for red liquid and purposely avoiding euphemisms in your messaging. What has been the feedback so far?

I also didn't really grow up with that, so it's definitely been a learning curve. The feedback has been super mixed. There are people who see it and they're super excited and inspired by it. Then there are people who think it's the grossest thing they've ever seen and worthy of death threats. If anybody ever wonders if period stigma exists, they should just look through the comments on some of my period blood videos, because the amount of hate on them is motivation. It's just a lot of people who are like, "This is disgusting. Nobody wants to see this. There's a reason periods are private."

A lot of that pushback is just really encouraging. I've never had a moment where I'm wondering if the work we're doing is really necessary. On a personal level, it's surprising for my friends and family. I live with my boyfriend, and he has to get used to me spending more time in the bathroom; he hears me making TikToks, like showing my underwear and showing my used period pads. That's definitely new for him. All my friends are like, "Oh gosh," about seeing their friend's period blood online. But our values align, so they understand my intentions. They know why I do what I do.

At the same time, I think they can all acknowledge that the content I'm trying to make answers questions they had. They've never seen period blood clots on someone else. I have friends who are like, "You know, this is what I learn from your content." I've had grown menstruating friends say they did not really realize that period blood and pee don’t come out of the same hole. That's something they learned from the content. Those kinds of comments and feedback are always really affirming.

You started the nonprofit Period at 16. How did you decide to go from that to starting August, a for-profit company?

It was not something I ever expected. When I started the organization, I didn't even know I was going to do it beyond high school. I didn't know that it could be a career. I was always learning on the job. Eventually, the nonprofit got to a certain size where most of my job as an executive director was raising money and doing development for the organization, and I had this internal struggle with trying to push this industry to change while also being reliant on that exact industry for funding.

I always felt at odds with that. I also had this growing passion to push the industry to care inherently more about impact, but in spending six years as the executive director of this organization where a large part of our programming was about distributing products, I learned so much about the product and so much about the supply chain. For years, I was really growing my own thesis in my head of how the products could be better.

It was constant, ending my days with this frustration, thinking if I were in charge of a brand, this is what I would do differently. I've had actual conversations with people at [existing] companies [about] their hesitation to make those changes. I'd spent years working on legislative advocacy from the nonprofit angle and feeling like there's something unique about the power brands have in this consumerist/capitalist world to dictate the period stigma. As a nonprofit, I was pushing brands to do that and reaching a roadblock, realizing they were the ones that held a lot of power in cultural change capital.

All that frustration boiled into me in 2019 saying, "Yeah, my heart is not in this anymore.” I'm passionate about the issue, but I felt I could make so much more of an impact if I approached it from a different angle. While the vehicle by which I'm doing my work has shifted, my mission and goals and the things that I want to achieve have very much stayed the same.

You were involved in some controversy with Period a couple years ago when other activists accused you of monopolizing the period care space. How have you learned and grown from that experience?

Well, I think the best way to explain a lot of this is in the context of what we've seen just in cultural conversations around the girl-boss trope. I stepped into my career at age 16 in 2014, [when] being a girl boss was literally on the rise in pop culture, and I very blindly leaned wholeheartedly into that. A lot of [criticism] of girl bosses is that they hog attention [and] the mic, [focus on] incremental progress, and don’t approach issues in the most intersectional way. A huge part of what I've learned is being more mindful about taking certain opportunities, sharing the mic, sharing the stage, and checking my own privilege at every point.

I definitely did not do a lot of my own reflection, or honestly, sociological learning over what it meant to be an Asian American and why I have certain opportunities over Black activists who are in the same space and come from less privileged backgrounds. So, a lot of what I learned was really understanding my own identity and how it comes into play in the work I do, and from there, being a lot more mindful of how I operate in any space. I think that's really important.

I also learned I didn't have language for things, like scarcity mindset versus abundance mindset, but that’s something I've been really interested in learning. Scarcity mindset was definitely a learned behavior from my trauma, from having immigrants in my family, and growing up with those narratives. I’m trying to be mindful and aware of that to shift to more of an abundance mindset — that's really about thoughtfulness and starting at the individual self-care level.

From when I started my career until I met a lot of this public backlash, I never heard these terms. I knew about the model minority myth, but I never understood or took a class or had been a part of conversations where it was like, "OK, the model minority myth is rooted in anti-Blackness and was created in white supremacist systems." I'm very thankful to have had the opportunity over the last few years to dive into a lot of that learning.

I've always been so passionate about the work that I do, sometimes in a risky way where I just throw myself into it and I'm like, go, go, go, go, go. The backlash really taught me to slow down, and ask myself, “What do I do so I'm acting and moving forward in the most thoughtful way — but also, why am I doing this? Why am I doing it in this way? Am I the best person to be doing this?”

“I've never had a moment where I'm wondering if the work we're doing is really necessary.” -Nadya Okamoto

You touched on your relationship with your Asian American identity, which you've spoken about in the past. How are you feeling now?

I'm still really confused and searching for answers. I've felt really empowered over the last few years with the Stop Asian Hate movement. I think that it's really unfortunate that it took a rise in anti-Asian hate crimes to create that trans-national solidarity. But the feeling of community and solidarity with other AAPI communities has been empowering. A lot of my journey around understanding my own identity has been really complicated over the last couple of years. Because I’m realizing I don't know anything about my roots. I know I have this family from Japan — my dad's an immigrant from Japan, and my grandparents are from Taiwan; they experienced the impact of World War II firsthand.

But I don't have contact with my dad anymore because he was abusive, and I was disowned by my grandparents last year and have no contact with them. A lot of why I was disowned was because I don't have traditional Chinese values. I share my period blood and trauma online, which is the opposite of maintaining secrecy and family honor. I feel that, for me, I'm just at the beginning of my journey, of trying to understand the history of my identity. I've actually been really thinking about doing [a DNA test] because I have all these questions about my ancestry, heritage, and history. In the last couple years of my college career, I took classes about Asian American history and tried to educate myself on anti-Asian hate over the last century, not just over the last two years.

Facing controversy publicly over my own identity really pushed me to lean into that. Because suddenly I was like, “Wait, who am I? How does my race play into the impact I have as a public figure?” All that to say, I think I've made a lot of progress. I've learned a lot, but I definitely feel like I'm just at the beginning of trying to understand what this looks like. I've grown up being told I was whitewashed and like a “banana,” very assimilated, like I don't know anything about my heritage [and] cultures. I don't speak another language. This is all I know. So, I feel like it's been that paradox that I've been existing in.

Do you have any words of wisdom for those looking to disrupt historically white spaces and industries?

Community is everything. I grew up in Portland, Oregon, which is one of the whitest major cities in the United States. I've seen my friend group and my inner circle communities become more and more diverse. That's so important, because any sort of space where you're not the norm or what you're pushing for is not the norm is exhausting, [but] you only know you're making progress if you're getting that pushback. Because of that, having community and a support system has been really important. But also, just making sure that I'm taking care of myself and sleeping eight to 10 hours a night. There's a reason why, especially in more activism-related communities, there's so much burnout. We're not really taught to, I don't know, prioritize sleep. That's something that's been really important.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.