What does "taking up space" actually look like for marginalized people?

A therapist explains how we can stop shrinking ourselves and start thriving.

“Don’t be afraid to take up space.”

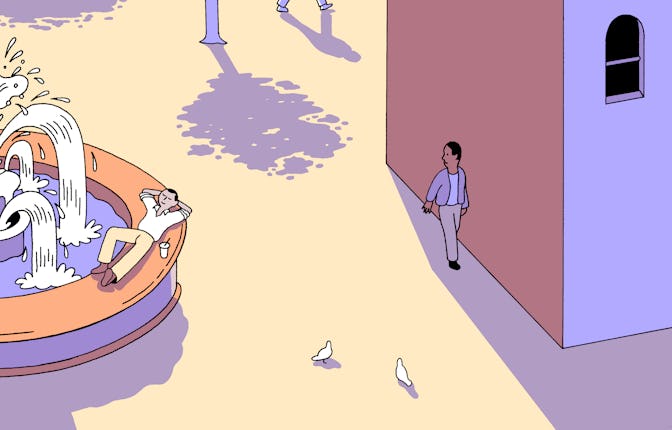

TikTok and Instagram stays spilling over with some variation of this advice, usually aimed at BIPOC, LGBTQ+ people, and other marginalized communities. As I scroll through these posts, I recall all the times I shrink myself — sometimes literally, like when I step off the pavement to make way for someone walking toward me; sometimes figuratively, like when I rein in a rebuttal to a cis man’s argument.

I 100% agree that I deserve to take up space, as do other marginalized people — but how? Taking up space is an abstract concept when you’ve been socialized your entire life to do the opposite. As an Asian woman, I learned from an early age to be quiet and obedient, and to prioritize others’ needs over my own. It’s what my family — and society — expected from me.

To overcome this mental block, I turned to Alex Jenny, a.k.a. The Drag Therapist, a licensed clinical social worker in Chicago. She broke down what taking up space actually looks like, and offered insight on how to practice it day-to-day.

Let’s start with the basics: What does taking up space even mean? Simply put, it’s “giving yourself permission to make room for your authentic emotions and feelings and boundaries,” says Jenny, who also uses they/them pronouns. When you take up space, she explains, you don’t feel like you need to succumb to the pressure to make yourself small, hide parts of yourself, or — if you’re a person of color — to subjugate yourself to white supremacy and values, in order to move through the world.

If you have a marginalized identity, though, you may have a tendency to make yourself small. You might shy from negotiating or let colleagues talk over you at work, Jenny says, or hide your true feelings in romantic relationships so as not to scare away your S.O. Maybe you constantly step aside for others in crowded spaces. “There’s so many different examples of how that can subconsciously show up in someone’s life,” Jenny tells me.

This impulse doesn’t materialize out of nowhere, though. In fact, it’s a totally understandable response to the messages you’ve received about your identity. If you’re a woman, you were likely socialized to not only be physically small, but to be well-mannered in ways that men aren’t, Jenny points out. You might’ve learned to avoid conflict based on the widespread — and erroneous — belief that if someone reacts negatively when you speak up for yourself, the resulting conflict is your fault.

“As a queer and trans person… I’ve been told that my queerness or trans-ness is unprofessional,” Jenny says. “The way that I dress or speak or carry myself is brash or not tactful, takes up too much space, is distracting.” These responses came up often when Jenny was exploring her gender authenticity for the first time, and people read her as “a man in a dress,” an image that many deemed unprofessional, and even sexualized.

And because she’s Asian, people also expected Jenny to be quiet and submissive — “the whole minority myth playing out, meaning that I needed to not draw negative attention to myself,” she says. Meanwhile, growing up with immigrant parents who weren’t always attentive to her emotional needs made her internalize the idea that she needed to take of herself, which meant not sharing her feelings or needs. I can relate: I worried that asking for what I wanted would only add to my parents’ stress over figuring out life in the U.S.

In a similar vein, if you had a neglectful or emotionally volatile parent, you might’ve internalized the idea that their emotional wellbeing is your responsibility, Jenny says. “Therefore, you make yourself small in order to accommodate this other person’s needs.”

While I understand the pressures that marginalized people face to shrink themselves, I personally struggle to resist them. But according to Jenny, I’m not alone — nor do I need to be so hard on myself. For starters, tolerating uncomfortable reactions from others to taking up space, such as comments about how “you’ve changed” or “you’re being selfish,” can be incredibly difficult. “If you don’t have enough of a strongly developed sense of self, then that can really get to someone,” she explains.

And crucially, “there are actual, real consequences to you taking up space that can’t be downplayed,” she says. “If we’re talking about a trans person taking up space, for example, in certain contexts, that might actually put you in danger.”

In other words, if you want to learn to take up space, you also need to be realistic and consider the ways the world punishes people for doing so, Jenny says. Here are some pragmatic, actionable steps you can take in your everyday life to start taking up the space you deserve.

Don’t be apologetic about what you like

“There are so many people that I work with who are so embarrassed by their hobbies or the things they enjoy,” Jenny says, whether it’s Taylor Swift or bad reality TV. They feel the need to hide them or share them with only certain people.

“If that’s what you like, that’s what you like,” she says. “We’re all suffering in this world and if that helps you suffer less, that’s ok.”

Practice taking up space with friends

These are people who you feel comfortable talking to about the emotions you might be experiencing in a given day, Jenny says. Ask them for explicit permission to vent by saying something along the lines of, “There are some things I really want to get off my chest. Is it ok if I take up space right now and do that with you?”

Repeat a mantra to yourself

As a trans woman, Jenny has learned to cope with people staring at her in public spaces by telling herself, “I deserve to take up this space. They’re staring at me because I’m so beautiful.” Tell yourself whatever you need to in order to make yourself feel empowered in situations in which others would prefer you to hide yourself or make yourself small.

If you’re ready to practice in public, start small

Assuming that your intuition and nervous system tell you that it’s safe to do so, try challenging yourself in small ways to take up more space in public, like resisting the impulse to step aside when you see someone walking toward you. Or, like, Jenny, learn to meet others’ gazes. “This person is staring at me — why do I suddenly feel the urge to look down?” she says. “I’m going return this person’s gaze and make them as uncomfortable as they’re making me feel.”

Expand your body

If can’t take up space in a real life context just yet, Jenny suggests making a symbolic commitment to doing so through breath work. “Notice your inhales and exhales,” she says. “Don’t be afraid to make sounds with your breath.” You might find yourself surprised by how often you restrict your own breath in trying to shrink yourself. You could also literally make yourself as big as possible through a dance or yoga practice.

Movement can help not only connect the dots between your physical sensations and emotional needs, but tolerate the negative reactions and other stresses of taking up space, Jenny says. You might find it easier to, say, call out a professor for saying something problematic even if you feel anxious because you’ve practiced calming your body and know that you’ll tend to yourself after this uncomfortable interaction.

Ultimately, you might even learn to build awareness of your anxiety as a sign that you need to speak up, not shut down. “If we wait for that anxiety or that negative feeling or sinking feeling to go away before we speak up, we’ll never speak up,” she says. “It’s being able to move through that feeling… notice the discomfort, and do it anyways.”