17-year-old Hayat Muse is fighting to end education inequality for the next generation

When Hayat Muse was four, she left Kenya with her mother in search of a safer and more promising future. They ended up in North Minneapolis, a popular landing spot in the city for African immigrants. "My mom is a person who never really had access to education," Muse, now 17, says. That made getting her daughter a proper education a top priority. But getting a good education was a significant challenge for an immigrant family laying down roots in Hayat’s neighborhood. "North Minneapolis is a predominantly black neighborhood, and unfortunately, when a neighborhood is predominantly black, that means that it deals [with] a plethora of very negative things," Muse says. "One of those is failing schools." The first schools Muse attended, she says, were charter schools that were wildly underperforming by most standards. "I didn't realize how under-resourced they were and how much they underserved their students," she says.

It wasn't until Muse got to high school that she realized just how far behind those schools had left her. "I felt like I was just struggling to catch up and it felt like I was so behind just because of the fact that I went to this under-resourced school," she explains. "That was my very first wake up call."

Muse said the experience of being left behind, and the lack of resources available to help her learn on her own, made her realize that the education system is not equal for all students. "We're all in school and we're all giving the same amount of time, but we're not having the same invested back into us." That understanding led her to start researching education equity, a concept that aims to promote fairness in opportunity and inclusion within the education system. Inequity in education can take many forms, whether it be a lack of access or opportunity for people based on their race, religion, socioeconomic standing, or disability. But regardless of who is getting less equitable treatment, the result is often the same: they are left behind by a system that will play one of the largest roles in establishing their quality of life.

"I realized I couldn't just sit around and wait for someone else to create change in my own neighborhood of North Minneapolis, because there's no Fairy Godmother or godfather that was going to come in," she says. That's when she decided to found Kow iyo Labo.

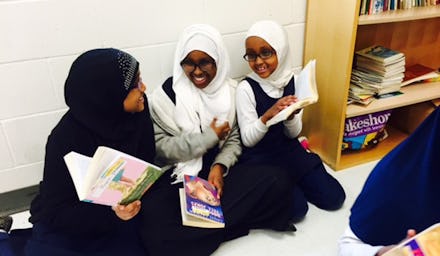

Kow iyo Labo, which is Somali for “one and two,” started as a tutoring and mentoring program within Muse's neighborhood. It started as just her, her sister, and a couple friends offering support for elementary school kids. Without any sort of backing to support them at the time, the tutors and their students would meet at the local library, which was more than happy to help. "The first place I reached out to was the library that I had been attending since I was a kid, and they were like, 'Yes, we are going to help you get started with this. We're going to provide you all the tools you need,'" Muse says. This was a major benefit to their efforts, as they had no funding at the time. "We didn't have any pencils, any workbooks, or anything to teach kids with."

Muse says her experience with the library is not the typical one, the version often imagined on TV or in movies. Her library, the Sumner Library in North Minneapolis, was more of a community center. "There was always a bunch of kids there using the computers. Some of these kids didn't have computers at home, so they would just come to this library right after school, and they use the computers or read books," she says. To Muse, the library was a more idealistic version of what the education experience could be. "Everyone got to access the resources like WiFi and books," she says. "Food trucks would come outside." She describes the library as her "earliest experience with education equity," and believes them to be important spaces to achieve those goals.

In the two years that Muse has been running Kow iyo Labo, it has grown well beyond its original structure. There are now three chapters of the nonprofit operating within Minneapolis, with more than 60 tutors currently working with more than 100 students. Over 250 kids have gone through the program already.

As the effort has grown, Muse has also guided it into branching out beyond just hands-on education. Kow iyo Labo is also involved in advocating for education equity policies and reforms, lobbying legislators, and working with experts to craft laws that will help get educational resources to communities that need them most. Last year, Kow iyo Labo established Minnesota's first student education advisory board. The organization also joined Solutions Not Suspensions, a coalition of education nonprofits pushing to fight against discipline disparities that plague public schools. Studies have shown that Black students in particular face considerably higher rates of disciplinary action compared to their white counterparts, creating even larger challenges for already disadvantaged communities. Muse's group was also involved in crafting and presenting a student inclusion bill to the Minnesota House of Representatives earlier this year, though the effort did not garner enough support to pass.

I make sure that I am still a tutor and mentor first and foremost because I think we forget about the human element - Hayat Muse

That hasn't stopped Muse from doing the work. She says that she has continued refining the student inclusion proposal, and is focusing on a number of policies that she believes would give students a more equitable education experience. "A huge thing that we're focusing on is the fact that BIPOC students are disproportionally disciplined," she says. They are currently pushing to have police removed from schools and working to make suspensions and expulsions, which cut kids off from access to essential resources and education, more difficult for schools to carry out. "Another big thing we've been working on is getting rid of the fact that preschoolers can be suspended and expelled," she explains.

Muse says she has seen firsthand just how disheartening unfair disciplinary measures can be for young people. "When I would see how easy my peers would get suspended and expelled, I saw how that got rid of their love for school, and how counterproductive it was." She says she often saw students unwilling to invest their time in a place that they felt like wasn't investing in them and was instead just punishing them. She has seen it in the young students that she has tutored, as well. "It's also definitely something we picked up from our students and our mentoring sessions, which are mostly about emotional support," she says. "We would definitely witness how negatively disciplinary procedures affect them."

Even with her active role in advocacy and policy-based initiatives, Muse is still involved directly in the tutoring and mentorship aspect of Kow iyo Labo. "I make sure that I am still a tutor and mentor first and foremost because I think we forget about the human element," she says. But her time with the organization may be winding down. Muse is a senior in high school and preparing for the next step in her own education. She plans on going to college and wants to continue pursuing education equity advocacy. While she says Kow iyo Labo will always be part of her plans, she believes it is important that the organization remains youth-run. "This is most likely going to be me stepping back and allowing the next generation of youth changemakers to take over and be leading this thing," she says. "I think youth voices in educational reform are so important."

While she's still maintaining a role for now and says it will be hard to let go of it, she knows that when she chooses to step away, "I'll be handing it over to our very accomplished, very promising, and very capable next generation." That next generation is one she helped empower to be exactly that.